Sports The hosting of mega-events is often cited as a cautionary tale for potential hosts, such as the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal.

In 1970, Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau confidently declared that ‘the Olympics can do no more harm than a man does in raising a child.’

Years and a billion dollars in debt later, a cartoon published in the Canadian journal Montreal Gazette showed Jeanne Drapeau as a pregnant woman contacting an abortion clinic by telephone.

Montreal finally paid off its Olympic debt in 2006. The corrupt and chaotically organized Games were a financial disaster and ushered in an era of excess and over-promising, when Olympic bids became increasingly extravagant: bigger and better, bigger and more expensive.

Hosting international sporting events like the Olympics, FIFA World Cup and Commonwealth Games has become a gamble.

Cities have to weigh the vast and often uncontrollable costs against the extraordinary benefits of two weeks of economic growth, some investment in sports facilities and infrastructure, and fostering local pride.

Financial gambling rarely pays off. India to be held in Delhi in 2010 Commonwealth of Nations 25 million dollars were allocated for the meeting.

Their price was 11 billion dollars, which is the most expensive price in history. Olympic Games average about double their initial budget.

That’s why when the Prime Minister of the Australian state of Victoria, Daniel Andrews, on Tuesday, 2026 Commonwealth Games canceled the plan to host , perhaps they wanted to make a decision before it was too late to back out.

“What has become clear is that the cost of hosting the Games in 2026 is not the $2.6 billion that was budgeted for,” Andrews said. In fact, it is at least six billion dollars and it could be as high as seven billion dollars.’

Their sudden demise sparked a controversy. The Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) accused him of ‘gross exaggeration’, claiming that he had quoted $4 billion in spending at a meeting just last month.

The CGF was also upset that only eight hours’ notice was given before the announcement.

August 7, 2022: Arshad Nadeem of Pakistan competes in the javelin throw events at the Commonwealth Games (AFP Ben Stancil)

Political opponents of Andrews described it as a ‘humiliation’ for the state of Victoria, while Commonwealth Games Australia CEO Craig Phillips claimed the state government deliberately ignored recommendations to move the events to Melbourne’s stadium. and tried to proceed with expensive temporary locations in Victoria.

Internal politics suggest that this is not just a financial decision, but also about popularity.

Hosting major sporting events is becoming increasingly unpopular with cost-conscious local populations and politicians reluctant to become the face of debt-ridden sports.

When bids are put before the public, they are consistently rejected.

In 2018, the people of Calgary voted ‘no’ in a referendum on hosting the 2026 Winter Olympics.

It was the 11th consecutive city to vote against hosting the Olympic Games.

The Commonwealth bidding process currently paints a picture of a very unexciting game of musical chairs.

Victoria only made the late move because the games in Birmingham had to be moved from 2026 to 2022 to replace Durban.

who had failed to stabilize his financial affairs. Durban was the only backup choice to replace Edmonton, which soon ran out of funds and had to give up.

The Commonwealth Games should, in principle, be cheaper than the Olympics, but fundraising is still difficult.

An independent report prepared by the British government said that the 2022 Games in Birmingham Great Britain has contributed more than £87 million to the economy, which is almost as much as it has cost.

It is rare that expenditure and income are equal because most cities are not well prepared to host the Commonwealth Games.

The reputational benefits of playing host are complex in the modern world.

The Commonwealth Games are sometimes referred to as friendly games but this does not deny their roots in the monarchy.

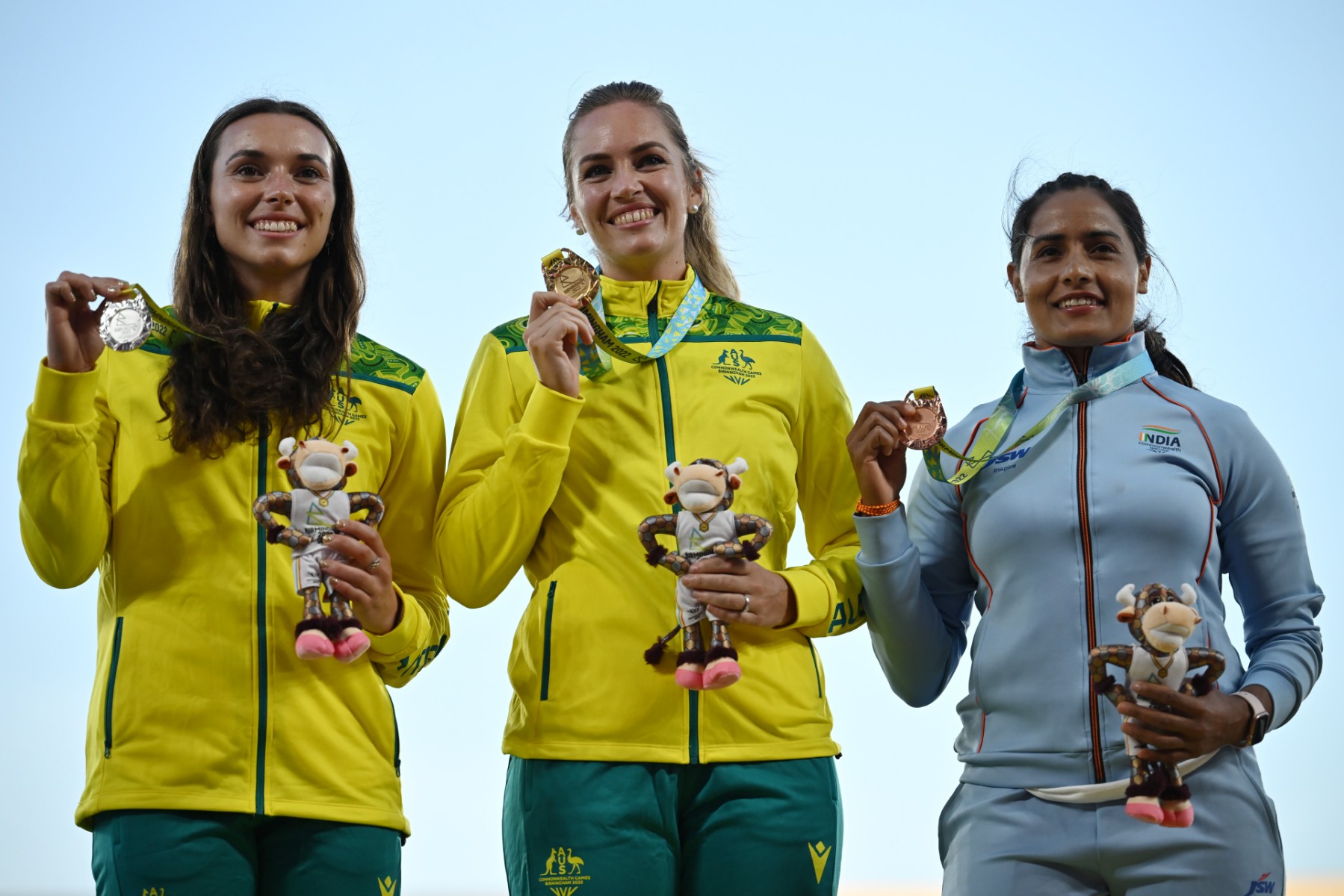

August 7, 2022: A picture of the winning athletes after competing in the javelin throw events at the Commonwealth Games (AFP Ben Stancil)

The date will now only be highlighted by the upcoming centenary edition in 2030 which marks 100 years since the first edition when they were called the British Empire Games.

The CGF website announces that the Commonwealth is entering an ‘era of renewed relevance’, whatever that means.

In fact, it’s a process that feels lost in the 21st century.

Last year, Tom Daley criticized countries that outlaw homosexuality. It is difficult to explain in sporting terms why we need to know who is the best in coastal sailing in some British territories and former colonies.

And so the desire to undertake such a project is becoming increasingly limited.

It is financially risky and politically risky. As Andrews explained on Tuesday: ‘We’re not going to invest that kind of money and it’s not going to be taken from other parts of government to put on a 12-day Games.’

This section contains related reference points (Related Nodes field).

With only three years to go, there is no clear candidate for the 2026 Commonwealth.

Rather than start a battle for ownership of the first Games since King Charles III’s accession, Victoria’s announcement has paved the way for other venues to fall in line.

New Zealand will not host. Sydney is not interested. Not even Melbourne can do that. Australia State governments across the board have refused.

The only major city that has the infrastructure for them in such a short period of time is probably the UK or Canada I may be the one who can step in to save these Games from being canceled altogether for the first time since World War II.

And even if the 2026 Games are ultimately saved, the CGF’s woes are far from over.

The bid for 2030 in Hamilton, Canada, has already failed: there is still plenty of time to make the centenary games better and bigger and pass parcels compared to previous games.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘2494823637234887’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

#country #host #Commonwealth #Games

**Interview with Sports Analyst Dr. Ayesha Malik on the Financial Risks of Hosting Mega Sports Events**

**Editor**: Thank you for joining us today, Dr. Malik. With the recent cancellation of the 2026 Commonwealth Games in Victoria, what can we learn from the situation surrounding hosting mega events?

**Dr. Ayesha Malik**: Thank you for having me. The cancellation reflects a growing concern among cities about the immense financial burden associated with hosting such events. History has shown us disasters like the Montreal Olympics in 1976, where the city ended up with a billion-dollar debt. The primary takeaway is that these mega-events are more gamble than guaranteed gain.

**Editor**: Many cities have hosted these games in hopes of economic growth but have faced massive debts instead. Can you elaborate on that?

**Dr. Malik**: Certainly. While hosting events like the Olympics or Commonwealth Games comes with the promise of short-term economic boosts and international prestige, the costs often soar beyond initial budgets—in some cases, doubling or tripling them. For example, the Commonwealth Games in Delhi spent an astonishing $11 billion, far above its original $25 million estimate. The ballooning costs tend to outweigh the benefits.

**Editor**: The decision to pull out of hosting the Commonwealth Games occurred after budget estimates drastically increased. What does this suggest about the future of hosting mega-events?

**Dr. Malik**: It suggests a shift in public perception and political sentiment. Major events are facing strong resistance from citizens who are often wary of the long-term financial impact. When Victoria’s Prime Minister Daniel Andrews stated the projected costs could reach upwards of $7 billion, it aligned with a broader trend where local populations are rejecting bids due to financial risks.

**Editor**: How might this affect future bids for major sporting events?

**Dr. Malik**: Future bids will likely face greater scrutiny. Public referendums have already shown that citizens increasingly oppose hosting these events. As seen in Calgary’s rejection of the 2026 Winter Olympics, cities may need to rethink their motivations for bidding. If the public sees these events as financial liabilities rather than opportunities for growth, the landscape may shift dramatically.

**Editor**: is there a way for cities to mitigate these risks if they still aspire to host mega-events?

**Dr. Malik**: Ideally, cities must prioritize transparent budget planning and community input. Collaborating with event organizers to establish realistic financial projections and exploring alternative funding models could also help. Additionally, focusing on long-term benefits such as infrastructure improvements and community engagement could provide a more balanced view when bidding for these events.

**Editor**: Thank you, Dr. Malik, for your insights. It seems that while the allure of hosting mega-events remains, the associated risks are triggering a much-needed reevaluation of their feasibility.

**Dr. Malik**: Thank you for having me. It’s definitely a pivotal time for sports hosting.