At 27, Samba Peuzzi has already built a trajectory, started ten years earlier in the shadow of the Rep’Tyle label. Today, following Dip Doundou Guis, he is the standard bearer. The child from the distant suburbs of Dakar hit the nail on the head, found the flow and the tempo, the words and the sounds that made him popular among young people, in a country where those under 20 represent more than half of the population. Suffice to say that the long young man has gained weight, especially since his musical curiosity, his taste for dance and fashion, make him an unclassifiable artist. Comparison is not right, but like Stromae, the rapper has a global vision, and thinks with his team regarding the smallest details of his clips, his strategy, his collaborations. The latest has him appear alongside Rema, one of the stars of Afrobeats, the genre that has become king in Nigeria, and now in Africa and in the diasporas. How, from the neighborhood, do you make your voice grow in Senegal, then from Senegal do you take it to the rest of the world? This is what drives Samba Peuzzi, whom PAM met in Dakar, as he prepares a new EP to follow up on his first album Senegal Boy (2021). Samba is laid back: let’s sit down with him, and listen to what he has to say.

Can you tell us where this name comes from, Samba Puzzi?

My real name is Samba Tine, but my stage name is Samba Peuzzi: the name came naturally because when we were little, we did dance: djerk, break dance… we had a group that was called Posey gang (posey as “posed”). And each of us had his first name and added Posey. One day, wanting to write the name on the networks, I wrote Samba Peuzzi, and I left it like that. Afterwards, when I started to sing, I wanted to change the name but it was already gone: I told myself that I had to let it go, it was actually original.

You were still a student, what did you listen to at that time?

I listened to everything: mbalax, rap, spiritual sounds like the thiant (spiritual songs of praise), the Mouride songs (one of the great Senegalese Muslim brotherhoods), because I was born in the suburbs and you can not escape it. So you also learn to sing that. It’s something that makes us know our religion, it educates us.

From dancing, how did you get to singing?

I started getting interested in music around 2012-13, but it was just for fun. I was dancing but I liked being the star too much, I said to myself that I was going to try to sing. And then I met the guys from the Rep’Tyle Music label and I got to know people like Dip Doundou Guiss who is like a big brother to me, I also met the director Idy, Bizon, by meeting them they saw a talent and said to me: you, if you continue to rap it will be fine because you have your own style “. Dip gave me strength from the start, he included me in his second album, and let me do a verse that was a hit.

In this verse, I said: “the rappers here, their eyes are like my neighborhood, they flood too quickly “. And the punchline captured the audience, it marked people. I said to myself: why not represent my district? In my neighborhood (Diamaguenn – Diacksao, just east of Pikine, Editor’s note), there was no rapper known to the public at the time. And then I said to myself: I’m going to start.

The title Ghetto Boy embodies this early period…

In this sound I said: I don’t look like where I live, I’m not dirty, your mother tells you: don’t come to this neighborhood, but I’m from Diack (Diacksao). I’m a boy ghetto ».

People had better think that if you live in the suburbs, you shouldn’t be clean, wear suits and ties, wear expensive shoes… but I broke that, and it influenced people in my neighborhood, they are less complicated. For me, the place does not determine the man you are, you can be in the suburbs and be a respectable person.

In your clips, you pay particular attention to aesthetics and fashion. Is it important for you?

It’s actually artistic. If you make music you have to like art, you have to like fashion. Before making music I liked fashion, that’s what I bring out, I want to make young people dream, tell them that you have to live: it doesn’t matter whether you’re in the village or elsewhere, or undermined according to your universe, try to show that you are stylish, even if you wear traditional outfits, try to capture people: be beautiful!

Do you choose the outfits?

I get involved but there are people who help me, I work with a friend on a clothing brand, and he helps me with a lot of things. Even if the means are not there yet, we want to prepare for one day to open textile factories… things that the rappers here often do not even believe: they believe that a rapper cannot achieve that, but we prepare a future where we can do it, in Senegal and in West Africa.

How do you work on your lyrics?

For me, it’s natural, it comes from my environment, from the suburbs where I grew up: I actually tell, I don’t think too much, I tell. Palpable things: if you look, you will see them. Like the ones I just talked regarding, that my neighborhood is flooding too fast. Usually I don’t write too much, I just come and talk, go ahead correct!

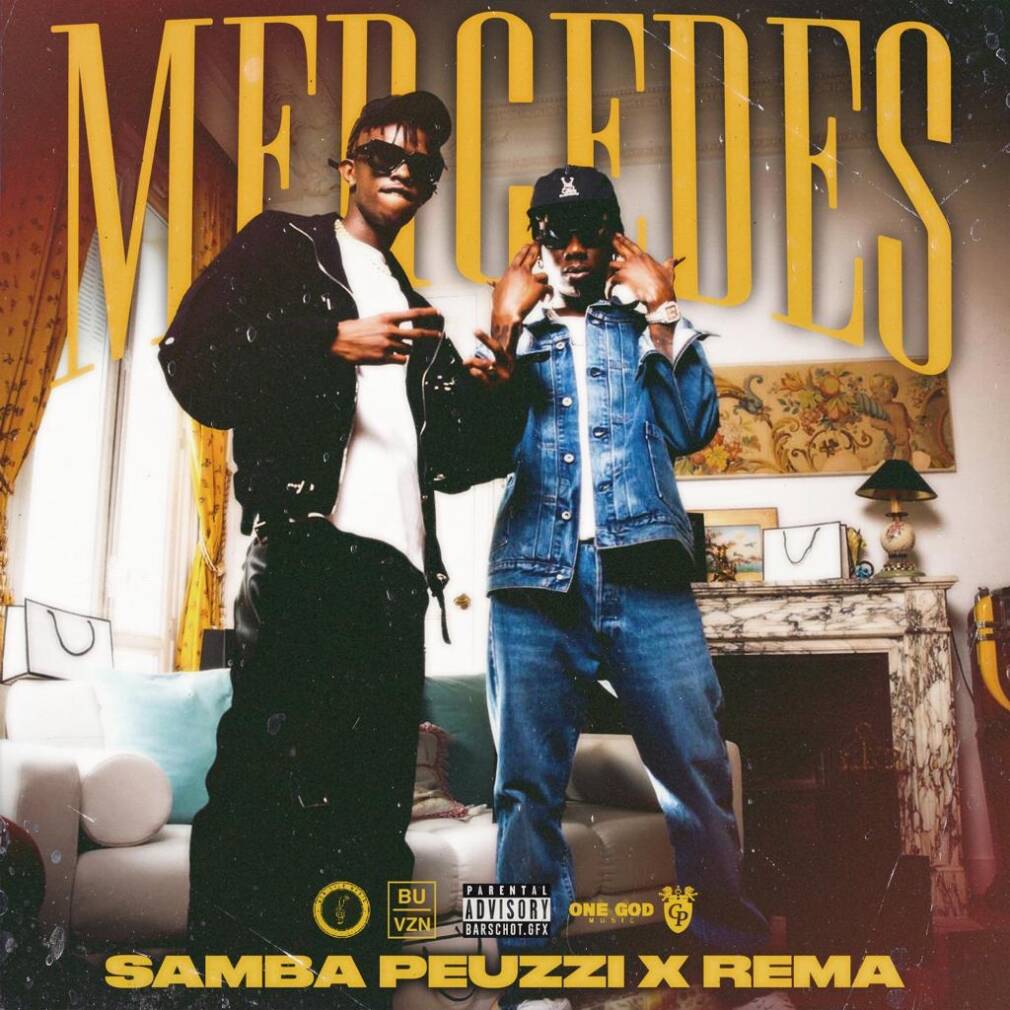

Since your beginnings, you have borrowed from different musical genres. There, you just signed a single with Rema, how did it happen?

That’s the stage we’re at now: we met producer Abraham from One God Music who saw us in a showcase here in Almadies (district of Dakar, Editor’s note). We said to ourselves that we were going to collaborate and for me the goal is to bring out Senegalese music as the Nigerians, Ghanaians and Ivorians have done. We made a sound called “Mercedes”. Abraham saw Rema and made him listen to the sound. He liked it straight away. When I went to play at the Badaboum in Paris, Rema was in town, and we thought why not? And he recorded there. It’s taking off in Nigeria, the sub-region, it actually takes…

Sounds more Afrobeats than anything you’ve done so far, you didn’t feel like putting tama (armpit drum, important in mbalax music) in it like you did in other sounds ?

To enter their universe, you have to do Afrobeats. If we arrived directly with our culture, Rema would perhaps understand less: if we persevere with Afrobeats and we start to have an audience outside, then we will bring in a little mbalax, a little sabar rhythm. We move forward slowly. The mbalax is something we were born with, you have to understand it first, you have to listen to it: there is the sabar rhythm, it’s our culture. And to try to make it liked, you have to adapt it to something recent, with new rhythms, and we are working on that with beatmakers abroad and here. It may take time, but it will.

The elders like Youssou Ndour, Baaba Maal, Ismaël Lô… they showed us that it is possible, they made sounds entirely in French, sounds without mbalax, but also sounds where they mixed mbalax with pop and other rhythms, so it’s this idea that we’re going to try to capture: to impose a new type of music like the Nigerians did, something new on a global level.

Why do you think hip-hop has become so strong in Senegal?

It’s youth. In Senegal there are a lot of young people, and if young people like something, it’s normal that it dominates: young people have imposed their culture, it’s natural. If the people up there or the investors had a vision, they would soon be investing in urban music, because that’s what’s going to dominate. It’s not help, it’s an investment: investing in young people who want to export music and collaborate with other artists.

Maybe also because rap allows young people to say things they can’t say elsewhere…

Rap is basically that: saying something that other music doesn’t tend to say, something that’s inside you, that’s real, that you feel. If the other young people listen to the sound, they will listen to it as if it were them and that’s what makes the connection between young people.

The problem is that people don’t understand youth, they see young people as children, as a father sees children. In Africa, that’s our problem: you’re never big. Even I am 27 years old, but the grown-ups in my neighborhood see me as a child. They think we are not allowed to speak or discuss certain things. But it would sometimes be necessary to give the floor to young people in large meetings where there are only grown-ups, at least to integrate a young person there so that he speaks. But each time we are told to go to school, school… whereas for us, even the street is school! There are children who have talent even though they haven’t even gone through school: those who are passionate regarding football, mechanics, etc. there are many options, and unfortunately many grown-ups didn’t get it: they say that young people are rude, but labeling young people as rude is what makes them rude. That’s what I saw. We must try to communicate with young people, integrate them into major discussions: we are young people, but we are not children, so we know what the older people are doing, and also what the younger people are doing, we are in the middle: so we should be speaking.

We know things that they don’t know, and they know things like events that happened when we weren’t born. We need them, as they need us. We have to discuss a lot of things, and for me that’s what will allow us to develop on all fronts, and to find solutions together.

This unconditional respect for elders comes from tradition…

Yes, but that’s why rap is good. What we are not allowed to say, we say in our sounds. And even if the adults don’t like it, their children will love it and sing it. We must try to find out what the problems of young people are, why many young people are on drugs, or in prison? It’s not that they’re mean or crazy, but because they don’t have the opportunity to speak or understand: many haven’t understood how it happens: the country, the president, it’s What ? They didn’t go far in school and didn’t have the opportunity to discuss certain things… it’s the grown-ups who have to help us with this, explain the side effects of the drug so that they understand: we needs these discussions between people. We are young and we have ambitions that can even exceed those of the adults.

Today, precisely, what are your dreams?

My dream is a better Senegal first, where young and old are together, where we make decisions together. Senegal is the country of the teranga, a country of peace. And the musical dream is to get our music out like the Nigerians did, like our great Youssou Ndour does, and that other young people with ambition see beyond Senegal. Music, but more broadly art, is something that allows you to “sell” the country: if you say Nigeria to me, I immediately think of music, not football.

I don’t know the president of Nigeria, but I know Wizkid, I know Rema, I know Davido. That’s the art that made it. So we have to work on this cultural level, with young people, because it is in the interest of the country. Like the national team that won the African Cup, if tomorrow we become a planetary star, Senegal wins.