The method of exploiting the springs and the waters flowing on the edges of the Vermion by our ancient Bereans is known from the study of the archaeologist Mr. Antonis Petkos (1989) and from some other salvage* excavations.

[ * Σωστικές ονομάζονται οι έκτακτες ανασκαφές για τη διάσωση των αρχαιολογικών ευρημάτων που ανακαλύφθηκαν κατά τύχη σε χώρο εκσκαφής κάποιου άλλου έργου.]

The gushing waters of a spring were initially collected in a stone-built tank of several communicating apartments for their purification. Then, by a channel made of hewn porolite stones and smeared with waterproofing materials, they were led to large-capacity tanks on the city limits. Cylindrical ceramic pipes were connected there, forming conduits, which, following the road network underground, made the distribution, where there was a need for water supply.

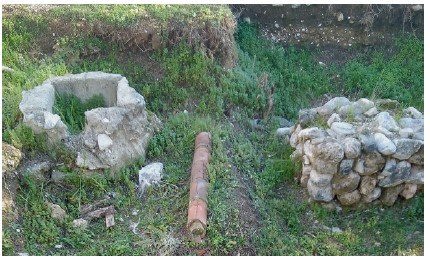

Left: remains of an ancient rock-cut cistern and part of an open stone conduit. Right: drawings from the aforementioned study by Mr. Antonis Petkos.

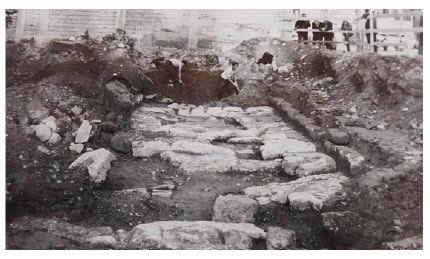

Partial view of complex of ancient baths in Veria (opposite I.N. Agios Anargyron). In the center, section of water supply pipe made of ceramic pipes.

Ancient reservoir near the “Arts Space” (probably part of the city’s water supply-sewerage network). It was studied, captured and covered forever… (Tsopelas Christou Archive)

A second network of conduits with clay pipes and stone channels collected the excess water together with that of the rain. It ran through the residential blocks meeting the needs of household cleaning and led them outside the eastern walls of the city (mainly) to water the flocks or irrigate the fields. There were strictly defined rules for the use of water (even the withdrawn ones), which all citizens had to follow. It is very possible that, following the example of Athens in this matter, the city’s agoranomist also carried out sanitary control of the entire water supply-sewerage network.

The absence of wells or domestic rainwater collection and storage facilities indicates that household drinking water needs were met by public wells. Some of them (as we already mentioned) were connected to the public aqueduct. But most of them must have been fed by the numerous gushing waters of springs within the city*.

[* Μέχρι και τον 20ο αι., οι ανάγκες των κατοίκων της Βέροιας σε πόσιμο νερό καλύπτονταν από εντός της πόλης πηγές οι οποίες διοχετεύονταν σε δημόσιες βρύσες].

Excavation of an ancient road with remains of an aqueduct. Veria 1964 (Archive of Antonias Bozini) .

Inscriptions from the Roman period also inform us that it was customary for the wealthiest citizens to undertake the high cost of construction and maintenance of water-sewage works, on the occasion of assuming some office or in memory of loved ones who have passed away. They also imply that there was an exact list of beneficiaries at each well, as well as regulation of water use rights. That is, although access to drinking water was the right of every citizen, the quantities to be consumed were not the same for everyone.

The beneficial contribution of Tripotamos to the rural occupations of the inhabitants (agricultural and animal husbandry), without doubt or dispute, was an important factor in the economic development of Veria.

However, as there are not enough archaeological findings regarding the method of its utilization in agricultural work, we will have to rely on written information from people who visited the city many years later (tourists). One of them, the French Delacoulonche, is the first professional archaeologist, who studied the antiquities of Veria in 1855. He visited many of its monuments, temples, mosques, cemeteries, residences and copied many ancient inscriptions.

In his travelogues he seems greatly impressed by the abundance of the waters that flowed through it: “When one approaches the clock tower, one is struck by the waters gushing from all sides, separating, meeting once more in the middle of the gardens, disappearing suddenly and purring. unseen under the figs and pomegranates, and then, a few paces farther on, they pour noisily from an opening in the wall and flood the road through which you will pass…”.

His enthusiasm prompted him to visit the slopes of the Vermian Mountains near the city, where he observed and recorded:

“…Climbing the foothills of Vermium, in the area of the two streams that water Veria (…) at most half an hour from the clock tower, we come across the remains of important works. First of all, there are many ancient and very deep wells, which had to be completely carved out of the rock. Near the second we hear the waters flowing noisily at the bottom, and which spring up from the ground regarding two hundred paces beyond. Additional remains of aqueducts are found over a fairly large area. These were not intended to carry water to the city, but to drain it to neighboring properties, at the time when all these flats were cultivated. The proof is that one of them, having irrigated a large area, discharges its waters into the torrent that flows to the south of Veria. In conclusion, they were rather irrigation canals than aqueducts. Where they encountered rock, it was enough to carve it. When he was absent, large volumes were excavated from the surroundings (big porolite rocks were taken out of the ground), which were hewn in the same way and placed in mortar (sealing material) or in cement bricks. I have measured the residuals of three of these channels. They do not present anything special, but they show the prosperity of the ancient city and the resources it derived from the cultivation of its lands. Dissatisfied with the plain of which they owned a significant part up to Aliakmonas, the inhabitants also had mountain properties and benefited from their abundant waters to fertilize their estates…”

The traveler’s texts lead the reader to think that the ancient inhabitants of the area had built a second, extensive network of canals, which served to irrigate their cultivated lands, utilizing the area’s rich reserves of Travertine sandstone.

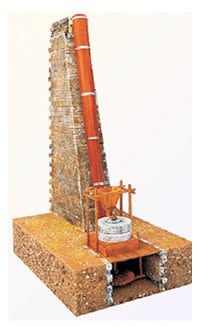

Of particular interest is an inscription-decree of the Roman proconsul Lucius Memmius Rufus addressed to the city of Veria, dated to the first half of the 2nd century. A.D. The viceroy, from Thessaloniki, makes remarks in a strict style regarding the regular shutdowns of the “High School” of the city (Veria) due to the lack of high school teachers who would take over its operating expenses. He then talks regarding the poor management of the revenues from the exploitation of “hydro-machines” (machines that operated with the momentum of water), which might have been allocated for this purpose. Among many other things, the inscription reveals that these water-powered engines were a bequest (posthumously given) of an unknown wealthy benefactor to the city.

It is the first written source that confirms systematic energy exploitation of the momentum of Tripotamos by the inhabitants of Veria. Its expert scientific scholars are of the opinion that the most likely meaning of the word “hydroengine” is “hydraulic grain grinding machine *”.

[ * Η χρήση τέτοιας μηχανής στον ελλαδικό χώρο καταγράφεται για πρώτη φορά από τον γεωγράφο Στράβωνα με την ονομασία “υδραλέτης”. Χρησιμοποιούνταν στα Κάβειρα από τον βασιλιά του Πόντου Μιθριδάτη ΣΤ’ τον Ευπάτορα. Στο ανάκτορό του τον είδαν για πρώτη φορά το 65 π.Χ. οι ρωμαίοι κατακτητές.]

From the beginning of the 2nd c. AD, dear friends, Tripotamos opened a new chapter in the development of Veria, leading it with its rapid waters into the early industrial age!

BIBLIOGRAPHY-SOURCES

Valavanidou P. Anastasia, The water mills of Macedonia, PhD thesis, 2008

Brocas-Deflassieux L., Ancient Veria-A study of topography, Veria 1999

Gounaropoulou L., Hatzopoulou M.B., Inscriptions of Lower Macedonia (between Mount Vermius and Axios River), Issue I, Inscriptions of Veria, Athens 1998.

Alfred Delacoulonche. Memoir on the cradle of Macedonian power on the banks of the Haliakmon and those of the Axius, Archives des Missions Scientifiques et Littιraires 8(1859) σ.67-288.

Nigdelis P., Souris G., Anthypatos says: a decree of the imperial times for the high school of Veria, 2005.

Petkos A., The water supply network of Veria, AAA XXII, 1989

Veris (Tripotamus) father of Veria (II)

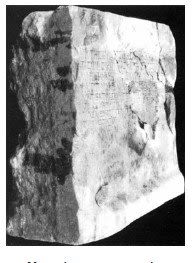

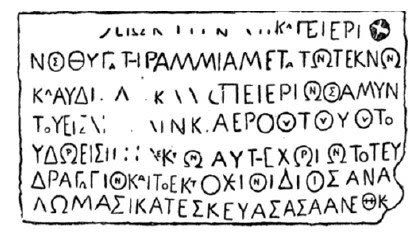

Marble inscription that, among other things, mentions the beneficiaries of a fountain and regulates the use of water (Archaeological Museum of Veria, find no. A 919, Source: Brocas-Deflassieux L.,)

Ancient Greek “hydralet” model from technewsingreek.blogspot.com

Copy of inscription by Delacoulonche. He mentions that Ammia Peierionos and her children (a family of large landowners of Veria) built with their own money a public “hydragoion” and an “ektocheion” in memory of her deceased son Claudios Aeropos.