Documentary filmmaker Andres Veiel presented his new film “Riefenstahl” about the notorious filmmaker and Nazi propagandist out of competition. After the death of Horst Berger, Riefenstahl’s last partner, Veiel and his producer Sandra Maischberger had 700 boxes full of new material at their disposal: letters, film clips, sound recordings, recorded telephone conversations. His years of research are firmly embedded in the film; Veiel says he spent 18 months in the editing room.

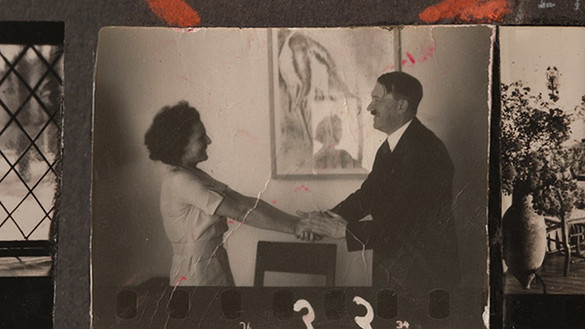

Using associative montage, Veiels looks behind Riefenstahl’s facade. Starting with her debut “The Blue Light” (1932), a mythical-romantic mountain film, “Riefenstahl” moves through the director’s works over the years. Central to this are “Triumph of the Will” (1934), Riefenstahl’s staging of a Nazi party conference, and her films about the 1936 Olympic Games.

Riefenstahl died in 2003 at the age of 101 and worked all her life to iron out her biography. Her staged facade crumbles again and again through off-screen shots in which the filmmaker gets angry in domineering outbursts of anger at the questions of her interviewees.

Riefenstahl says that she only documented and made art, never politics. Something that is never believed, because even if Veiel is not interested in painting a one-sided picture of the filmmaker in his montage of the Enlightenment, he still repeatedly exposes the woman as being caught between Hitler hype, radical (feigned?) naivety and fierce ambition. It is consistent how Veiel dissects the image manipulator using her own means.

»September 5« (2024). © Constantin Film

Tim Fehlbaum’s journalist thriller “September 5” is also about a different kind of montage of enlightenment. In it, the Swiss director tells the story of the terrorist attack at the 1972 Olympic Games, in which Palestinian terrorists took eleven members of the Israeli team hostage. After films such as Steven Spielberg’s “Munich”, he finds his own cinematic approach by telling the story of the terrorist attack from the perspective of journalists – the first to be broadcast live on TV and watched by, as the credits say, 900 million people.

The tightly staged, chamber play-like thriller stays almost the entire time in the Munich broadcasting center of the US channel ABC, where the sports journalists are taken by surprise by the events in the Olympic Village. With a fun cast including Leonie Benesch, John Magaro, Ben Chaplin, Rony Herman and Peter Sarsgaard, Fehlbaum celebrates the classic craft of television journalism on the one hand. At the same time, he poses journalistic and ethical questions: Which images are allowed to be shown and to what extent does the charismatic team play into the hands of the terrorists who can also see the images? “Is this our history or theirs?” someone asks at one point. The inglorious role of the German police is also addressed.

Both films are topical: because of their political references to the present and because both, in their own way, ask questions about the power of images.