- Andrew Harding

- BBC correspondent from Donbass, Ukraine

July 28, 2022

The French-made self-propelled gun Kaiser is one of a growing number of modern Western weapons in eastern Ukraine.

Soldiers on the front lines in eastern Ukraine say advanced Western weapons have stopped Russia’s heavy bombardment. But is this just a brief lull, or a sign that the tide of war is changing?

Five plumes of smoke cut through a clear blue sky on the hillsides north of Bakhmut. Bakhmut, an almost deserted agricultural town, has been bombed by Russia for weeks.

“This is not our life. No place is safe. I wish my life was over,” said Anna Ivanova, 86. She bent over with the help of a cane and pulled grass from her garden as two Ukrainian warplanes whizzed through the air.

Ten minutes later, five or more roars continued westward from a field of brilliant yellow sunflowers.

image source,Archyde.com

Bakhmut has been under constant attack from Russia for weeks

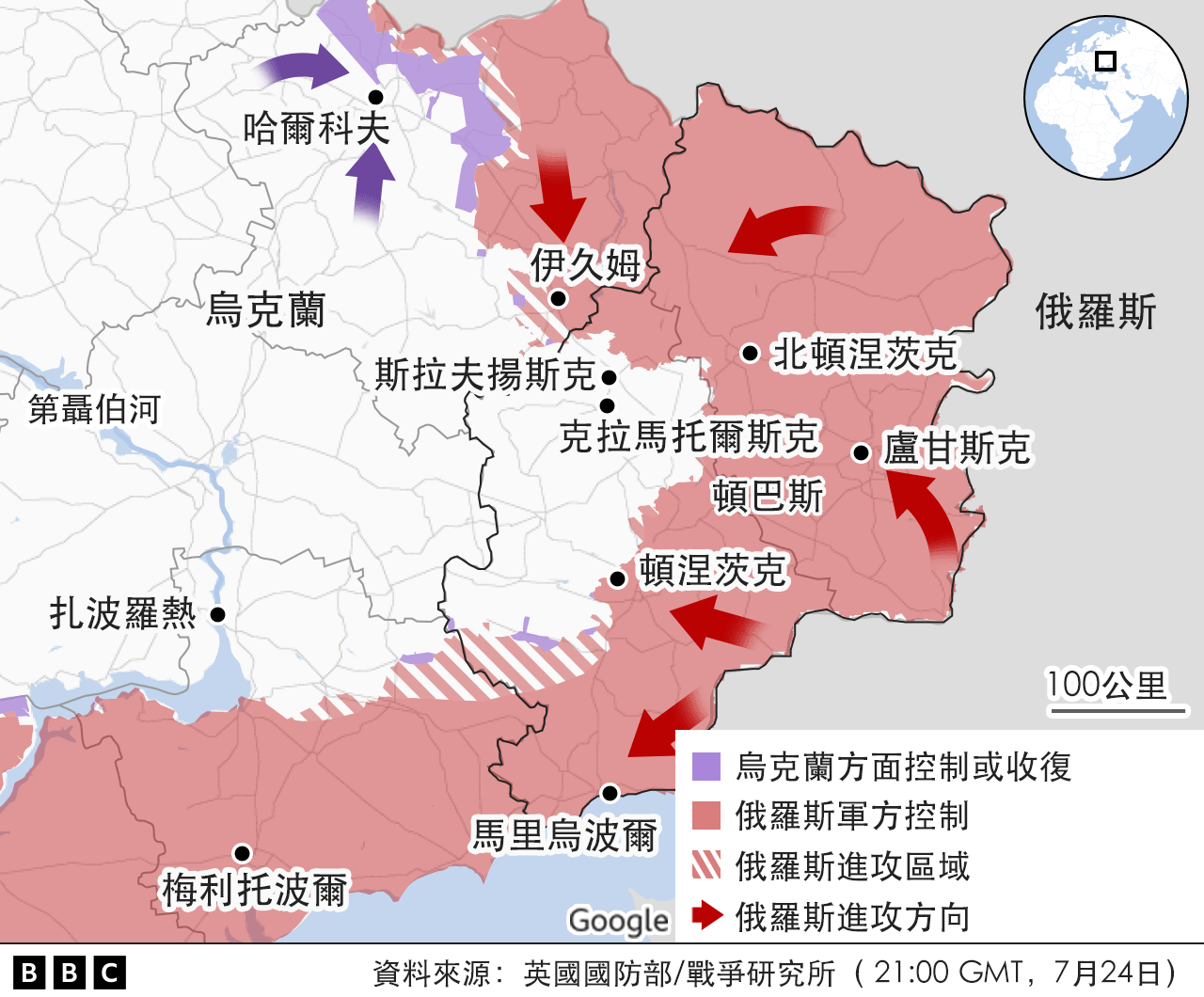

From the devastated city of Slovyansk in the north, to the abandoned villages near Donetsk in the south, anyone who drives close to the winding front lines in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine can sense the seemingly endless randomness of Russia. The heavy bombardment is still as crazy as ever.

But in the corner of a wheat field outside Donetsk, Dmitro, the commander of the Ukrainian artillery unit, said he was adamant regarding it. “They don’t fire very often. The rate of artillery fire (of the Russian units) has dropped by half. Maybe more, by two-thirds,” he said. He patted the side of a large green car next to him.

The car was a self-propelled gun with a huge barrel pointed to the south in Russian-held territory. This is the French-made “Caesar”, one of a growing number of advanced Western weapons that can now be seen on the country roads of Donbass. Dmitro and many here believe they are helping to turn the tide once morest Russia.

With a deafening explosion, Kaiser fired the first of three shells at Russian infantry units and several artillery pieces 27 kilometers away.

“We’re more sure now. We can hit further,” he said with a smile. Within a minute, the artillery team fired two more shells, and the car quickly left before the Russian artillery had a chance to track its location and fire back.

In recent weeks, Ukrainian civilians and soldiers have often been elated when drone footage and other videos uploaded to the internet appear to show a series of massive explosions in Russian-held territory.

These were widely reported to be large ammunition depots far from the front lines, but now within reach of newly arrived Western weapons, including the US’s Himars and Poland’s Krab self-propelled howitzers.

“Listen to the silence,” said Yuri Bereza, 52, a bearded 52-year-old who commanded a volunteer unit charged with defending Slavyansk. On a recent morning, for more than an hour, I visited the defensive trench network in the east of the city and might not hear any explosions.

“It’s all because of the guns you gave us, because of its accuracy,” Bereza said. “Before, Russia had 50 times as many barrels as we did. Now it’s more like five to one. Their advantage is now negligible. . You might call it the same.”

But Bereza, like Dmitro, stressed that Ukraine needs more Western weapons to launch an effective counteroffensive.

Yuri Bereza says Western weapons almost make Ukrainian troops as firepower as Russia

“They can’t beat us, and we can’t beat them. We need more equipment, especially armor, tanks, planes. Without these things, there would be a huge loss of life. That’s how Russia waged war. They threw away their lives. ,” Bereza said.

“Ideally, we want three times as many (Western weapons) as they’ve already delivered, and faster,” confirmed Dmitro.

But the lack of weapons is not the only factor that might hinder Ukraine’s determination to liberate the occupied territories. Despite the reduction in Russian bombing, Russian forces continued to advance towards the strategic town of Bakhmut, raising concerns regarding the lack of manpower and training in the Ukrainian army.

“There’s a simple trick,” shouted a burly figure. He lay on a dirt road, aiming his rifle, surrounded by forty attentive Ukrainian soldiers.

“Put your legs up like this,” the man said. A former British paratrooper, he was a member of a private organisation supporting a Ukrainian brigade that had recently arrived in front of reinforcements.

The Ukrainians are all volunteers with only a few months of basic training. Their commanders struck an informal agreement with Western instructors for a five-day training session.

“Of course, it’s scary. I’ve never seen war before,” said the 22-year-old commander of the unit. He is a lawyer and asked us not to give his name.

“It’s worrying that these people lack the basic warfighting skills of the West,” said Rob, another former U.S. Marine.

Private organisations including Mozart Group operate independently in eastern Ukraine

For now, Western governments refuse to send officials or contractors into Ukraine to help with recruitment and training. Some private organizations operate independently here.

“It’s a drop in the ocean. But it has an impact on a small scale,” retired U.S. Marine Corps colonel Andy Milburn said while watching a training session.

He stressed that his Mozart team had “zero” contact with and no support from the U.S. government, but criticized Western countries’ refusal to engage more directly as “nervous” and “short-sighted”.

“It’s ridiculous. But these people have lost too many people, they don’t have (enough Ukrainian instructors),” he said. “The West needs to plan for this now.”