Hava-khori

Thomas, who was born and raised in Aalborg, is taken to a cell after a medical check-up, which he has to share with four other men.

There is carpet on the floor, a sink in the corner and a steel toilet, which is only used as a chair.

This cell will be the only thing Thomas sees for the next month. With few exceptions.

When Thomas and the other prisoners have to leave their cell, they must always wear a mask over their eyes and face the wall. Photo: Martél Andersen

Over the loudspeaker, Thomas hears “hava-khori” being called. The other prisoners in the cell put on their flip flops and eye mask and get ready to leave the cell, so Thomas does the same.

They walk in a long line through the corridors and out to a 10 by 10 meter prison yard.

Thomas is sure that they must be whipped. It looks like a place where you torture people.

But it will turn out that this farm will be Thomas’ hell in the Iranian prison.

– One of the best moments of my Iranian week was when we were taken out for “hava-khori”, which means eating air. In other words, to get fresh air, says Thomas.

– The farm became my running arena, where I just ran round and round and round again and again.

– At the beginning there was only time for 80 laps, but gradually I ran more and more. My record was 439 laps, which is almost equivalent to the Limfjord race. I guess it’s an Evin record.

A touch of Hollywood

In addition to the two times a week when there is a farm trip, the first month is spent only in the cell or for interrogation. But then something happens.

The cells open and the corridor collapses.

In this amalgamation, Thomas meets Iranians who can speak English, so he suddenly gets an interpreter.

And then he meets Nik Yousefi. He is a film director, and films are Thomas’ greatest passion.

– Nik had a dream of coming to Hollywood, so we agreed that I would help him improve his English and he would teach me to get better at making films.

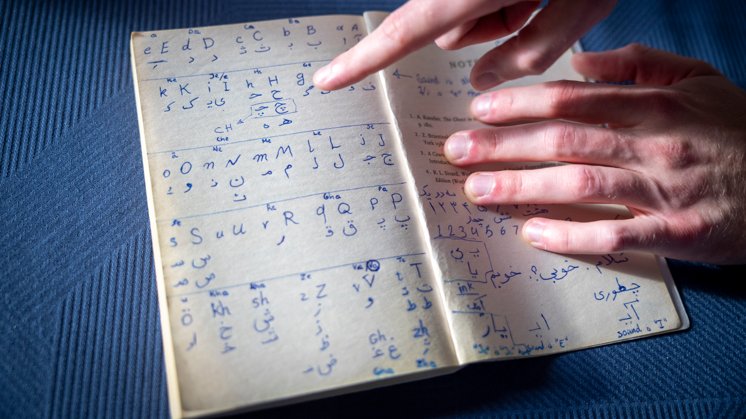

“The Power of Now” became Thomas’s Bible. It taught him to accept his situation. On the back page is the Persian alphabet written by a cellmate. Photo: Martél Andersen

Because even though Nik Yousefi is not the best at English at this point, the two find other ways to communicate.

– I had been in prison for over a month, and because most fellow prisoners could not speak English, I had become extremely aware of body language. I could hear one Persian word I understood and then I knew everything they were talking about from their body language. I used the same with Nik Yousefi. I stared very intently at body language and facial expressions, and then I understood almost everything he said.

First meeting with a judge

Time passes and although Thomas makes friends, he is very affected by being locked up. He still does not know what he is imprisoned for either, since he has not seen either a judge or a lawyer.

Only after 56 days does he come before a pre-judge and is accused here of participating in assemblies and breaking public order, as well as conspiring against domestic and foreign security.

A standard charge according to the other prisoners.

But that doesn’t help Thomas’ mood. He misses being creative like he used to, and he misses his family.

While incarcerated, Thomas created his own version of Monopoly called EvinPoly. One of the cards read: “You have been to the pre-judge, who has extended your sentence by one month. Move back 10 spaces”. Photo: Martél Andersen

Thomas is allowed to call home to his mother, father and sister at irregular intervals. The calls cost DKK 24 per minute, and the connection is not exactly stable, but it’s better than nothing.

At home, the family has contact with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, lawyers and anyone they think can help get Thomas out.

Thomas himself can do nothing but play along.

You can’t comfort everyone

More and more are being released, but not Thomas. Eventually, there are only about five of them left in the original corridor, so they are merged with another.

In the new corridor, the doors to the cells are also open, and there is a fridge, electric kettle and a television to share.

This makes the imprisonment more tolerable, but Thomas and the other prisoners are still pushed to the limit.

– Since I have been imprisoned for about four months, we sit in a cell and watch films. There are probably seven of us facing the screen, and then a new prisoner comes in who has almost just been imprisoned.

– He sits at the back of the cell and starts to cry. And everyone just looks straight at the screen. There is no one to comfort him as he just sits there and cries.

– After a while there is a cellmate who hands him a tissue box without really looking at him and then otherwise sits back to watch the film.

– There was no care, no one to comfort, because everyone was at a loss. No one had the energy to comfort him. After all, we were all under pressure and we all had to look after each other, but you can’t comfort everyone and be there for everyone. It may be cynical and harsh, but that’s who you stayed in prison.

Hostage diplomacy

Thomas manages to sit in prison in Evin for seven months before something finally happens.

Belgium has an Iranian terrorist in prison, and Iran wants him extradited in return for the release of a Belgian prisoner. But since Belgium won’t settle for a one-for-one swap, Thomas will be part of the exchange.

On 2 June 2023, Thomas finally arrives in Denmark again.

His hair is longer, his beard is bigger. And he has to live with a trauma for the rest of his life.

After being imprisoned for seven months, his hair and beard had grown so long that Thomas felt like the Viking the other prisoners compared him to. Private photo

– This coming home to one’s childhood home after seven months, where I have been cut off from the internet, food that tastes good, things you want to do, fresh air and sunlight and then suddenly sitting out on the terrace and being at home. It is the most insane thing for the nervous system that you can imagine.

– My nervous system was totally in reverse because it has gone from such great extremes in such a short time.

The final verdict

- The message comes on Whats-App from an Iranian lawyer and reads:

- “Dear everyone

- The judgment has been published.

- Thomas was sentenced to two years in prison, but the sentence was changed to

- a fine of 1,000 dollars.

- He is also banned from entering Iran for two years.

- Please let me know if you wish to appeal the sentence.”

The Man with the Dice by Simi Jan

The man with the dice

When the journalist Simi Jan contacts Thomas’ father, and later Thomas himself, with his proposal to write a book about his experiences, he is quite quick to say yes.

– The book has been my way of processing it all. Mentally, I was not at all ready to get out of prison, because it is such a huge contrast.

– I don’t know how to describe it if you haven’t tried it. It’s a bit of an “out of body” experience, where you drive on autopilot until the mind slowly falls into place. Then you land not only physically, but also mentally.

– The book has helped me land in a place where I now function regularly and normally. I haven’t had nightmares in a long time now.

Thomas hopes the book leaves people with a sense of a larger context from which to learn. Photo: Martél Andersen

The book with Thomas’ experiences “The Man with the Dice” will be published on Tuesday 12 November. Two years and 12 days after Thomas was imprisoned.

Desire to travel

Since Thomas came home, he has stayed away from social media and he maintains some of his routines from prison.

He still starts the day with a cold shower, he exercises, stretches and goes for a few walks. Now, however, he runs in running shoes rather than the yellow flip-flops he ran in during his prison stay.

– I can also still sit in a tailoring position, but I do it far less now.

Do you still have the guts to travel?

– Absolutely. I have to travel again.

– My final sentence gave me a ban on entering Iran for two years, and it is actually coming to an end now, he says with a laugh.

– No, I have no intention of traveling into Iran again. But with traveling and telling stories – I’ve only just started.

2024-11-10 19:01:00

#Thomas #months #hell #tells #story

Thomas reflects on the profound impact of his ordeal, using the process of writing the book as a therapeutic outlet. Private photo

- It’s important for me that people understand the reality of such experiences. Writing has helped me externalize what I went through, transforming raw pain into a narrative that others can read, empathize with, and hopefully learn from.

– Even if it’s difficult to relive those moments, it’s part of my healing process. I want to make sure that they are not forgotten, and that my story can spark conversations about human rights, freedom, and the fragility of our lives.

Through his book, Thomas hopes to shed light not only on his personal struggle but also on the broader issue of hostage diplomacy and the political complexities that come with it. He believes that stories like his can create awareness, influencing how we view such situations on a global scale.

- At the end of the day, it’s not just about me; it’s about all those who are caught in similar circumstances. If we can bring attention to these injustices, perhaps we can contribute to a shift in how these cases are addressed in the future.