The discovery of the first organism capable of surviving by eating only viruses might have enormous repercussions in several fields.

From bacteria to the largest mammals, including green plants, fungi and all other organisms, no matter which kingdom you are interested in, there are bound to be others who have developed tools to eat them. At this level, viruses are exceptions; there are certain organisms that can attack them, but no one has yet described an organism ” virus “, that is to say who feeds exclusively on viruses.

This shortcoming puzzles specialists for several reasons. The first is that viruses are very abundant; even in a perfectly healthy small pond, there are millions of virus particles capable of infecting a wide variety of different hosts. It is therefore surprising to find none who have opted for this diet.

And this inconsistency has almost turned into an obsession for John DeLong, a microbiologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, in the United States. With his team, he has been trying for several years to shed light on this gray area of the food chain. ” It seems obvious that lots of organisms end up with viruses in their mouths all the time, simply because there are very large quantities of them in the water. “, he explains in a press release from the university.

This is all the more surprising since, from the point of view of a micro-organism, viruses are particularly appetizing appetizers. They are composed of nucleic acids, nitrogen and phosphorus – essential building blocks of life as we know it.

Logically, it is therefore a delicacy that ” everyone should want to eat ,” insists DeLong. ” There are so many things that eat whatever comes their way. So there is definitely something, somewhere, that has learned to eat these very interesting raw materials. But testing this hypothesis was anything but trivial.

A trail from the plankton

In lack of concrete leads, DeLong therefore began by casting a wide net. He collected a large number of various microorganisms from a nearby pond before culturing them. It still remained to find them a potential meal – a terribly risky process, knowing the variety of possible interactions between the different species. To maximize his chances of success, he chose to work with cholorovirus.

These are species that parasitize the cells of microscopic green algae. During their life cycle, they explode infected cells. This has the effect of releasing carbon and other nutrients into the medium. And if DeLong chose them, it is because they have already been the focus of another important study on the place of viruses in the food chain.

Traditionally, researchers thought that these elements fed the higher levels of the food chain. But in 2016, biologist James Van Etten showed that most of this material was actually consumed directly by the microbial fauna in a vast recycling operation. This has therefore led some researchers, including DeLong, to look into the place of viruses in this feast for Lilliputians.

He therefore added chloroviruses to his culture before starting an observation phase. The goal: to find an organization, any one, that would treat the virus as a snack rather than a threat.

Halteriathe first TRUE virivore organism

Over time, he made an unexpected finding from a population that a population ofHalteria, a genus of unicellular ciliated microorganisms of the plankton family. These little beasts seemed to be doing surprisingly well. However, in microbiology, this is a very strong sign; this suggests that the species in question has access to a food source in its direct environment.

He therefore isolated these little gluttons before serving them a new portion. And his perseverance was rewarded. Because two days later, the trend had become very clear. The number of chloroviruses has been divided by 100, while the population ofHalteria was multiplied by 15. In parallel, in a second control group without chlorovirus, the bacteria rapidly withered away.

A very promising result. But before announcing a great discovery, such as the very first organism capable of sustaining itself solely on viruses, it is better to be sure of your fact. So the team embedded a fluorescent marker into the DNA of the viruses…and the bacteria’s vacuoles — the functional equivalent of the stomach in these organisms — quickly began to glow brightly.

Indisputable proof that a transfer of material was indeed taking place between the two populations. And the icing on the cake is that following the fact, DeLong and his colleagues managed to identify several other additional vivorous organisms. Jackpot !

Major implications in many scientific disciplines

« I called my co-authors shouting: “They pushed! We did it !“”, he recalls in the press release. “It’s exhilarating to be able to see something so fundamental for the very first time. And that’s not an understatement. In fact, it is even a major discovery which might significantly change the way we study food chains.

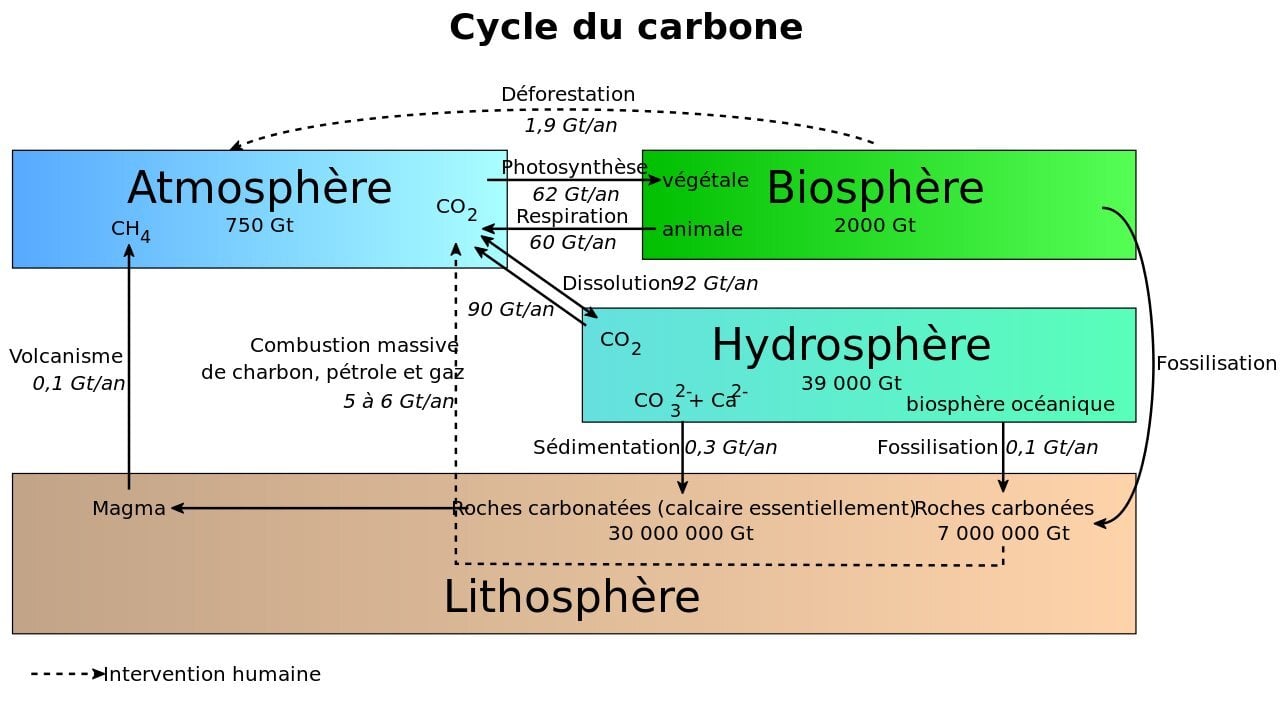

« If we multiply a simple approximation of the number of viruses, the number of ciliates [comme Halteria]and the amount of water on earth, we get a massive movement of energy up the food chain says DeLong. And it goes even further. ” If it happens on the scale that we think, it might completely change our global conception of the carbon cycle. »

As a reminder, the carbon cycle is a phenomenon of gigantic proportions which describes the life of a carbon molecule, and its passage through the various biological, geological, aquatic or atmospheric reservoirs of our planet. It is therefore intimately linked to life on Earth at absolutely all levels, from the physiology of organisms to the climate of the planet. Suffice to say that if viruses have a greater influence than expected on this cycle, it will therefore be a very important scientific development.

From now on, the whole challenge will be to document the life of these vivorous organisms directly in their natural environments. First, it will determine how they impact the structure of food chains, and the evolution and diversity of species. And at this stage, it will eventually be possible to redefine the place of viruses in life on Earth, with all that this implies for lots of other fields of research.

The text of the study is available ici.