- Daniel Brown

- BBC Mundo correspondent in Colombia

9 hours

image source, Getty Images

The Defense and Security policy of the new president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, has been described as “ambitious”, “bold” and, for the most critical, “provocative”.

Petro comes to power with two purposes in the matter: “total peace” and “human security”, as he calls them.

The first consists of signing peace treaties with the almost 30 armed groups in force in the country. The second will try to provide security not through surveillance or the persecution of criminals, but through opportunities, access to basic services and infrastructure.

The adjective ambitious is, without a doubt, the one that generates the most consensus.

Petro came to the presidency following a virtuous political career denouncing corruption and human rights violations. His plan for peace in Colombia goes along these lines: to leave behind the warmongering and persecutory strategies inherited from the Cold War, promote an international debate on the legalization of drugs and radically transform the unequal economic model that, according to him, promotes war in the country.

The worsening of violence in Colombia has continued in the month that Petro has been in the presidency: 12 massacres of the 73 so far this year have been reported and 13 social leaders have been assassinated.

El Friday, a police ambush left sevenagentis dead and added pressure to a government that, according to experts, does not finish clarifying how it is going to achieve peace in the midst of the war that the State is still waging once morest guerrilla groups and drug traffickers despite the peace agreement signed with the FARC in 2016 .

For his project, Petro needs the Armed Forces on his side, but his first initiatives within the military and police sphere seem to have generated more concern than confidence.

“Everything that has been presented in this first month has been a roller coaster that has us all with the creeps, without really knowing where we are goingsays John Marulanda, an influential colonel in the active Army Reserve.

From a different place, the security expert Jorge Mantilla points to a similar concern: “There is a high degree of improvisation and disarticulation of the announcements, and that complicates the relationship with the Public Force, whose role in the security strategy is not Of course (…) Human security, which in theory offers to expand the supply of State goods and services, exceeds the powers of that institution.”

Daniel García-Peña, former peace negotiator and director of the NGO Planeta Paz, shares the concern regarding the lack of clarity and the reaction of the Armed Forces, but is more optimistic: “The conflict in Colombia changed and it was necessary to rethink the strategy of the State to face it. Petro’s first decisions were necessary, they send clear messages regarding the priorities on the issue and they had to be taken quickly, at a time of popular, political, and legitimacy support.”

“Human Security is a positive initiative,” adds Alejo Vargas, an expert in security and violence.

“But the first part of the government must be focused on comprehensive security that includes public security in the regions, because if there is not a forceful response from the State and society rejecting violence once morest the police, we are going to continue in the common logic of these groups measure the government to see how it reacts”.

The murder of the seven policemen may create more conditions to talk regarding peace, but also increase skepticism towards Petro within the Armed Forces.

Since announcing Defense Minister Iván Velásquez, a human rights jurist who denounced military crimes for years, Petro has made his peace agenda the number one priority. Last week he presented a broad legislative project to support it. Even the rapprochement with the government of Venezuela, where some guerrillas take refuge, can be seen as part of that strategy.

These are, then, four unprecedented measures by Petro in Security and Defense in the recent history of this country at war that have shaken the military sector.

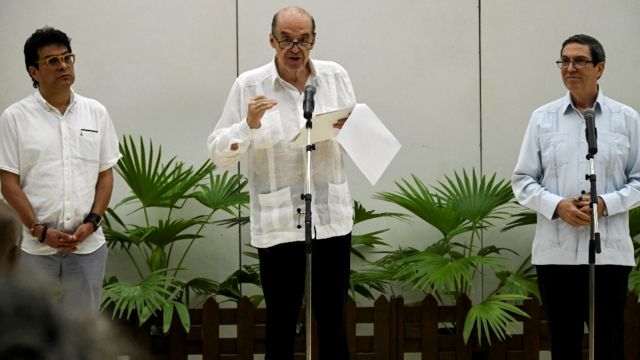

image source, Getty Images

1. Purge at the top of the Public Force

All Colombian presidents tend to rearrange the hierarchical structures in the Armed Forces as soon as they come to power. None, however, was as big and symbolic as Petro’s.

In less than a month, at least 70 generals and colonels of the Army and the Police – more than half – have been removed from their positions. Some because they are accused of crimes; others, without explanation. The announcements have been made in small drops, without formal mechanisms. There was a group that was informed of his dismissal at midnight. Another whose appointment was later suspended.

The concern of the experts is improvisation and that formal, traditional and academic mechanisms that used to set the guidelines for removals and appointments were skipped.

In his replacement, Petro has appointed colonels and brigadiers who supported the peace process with the FARC guerrillas signed in 2016, who are not accused of crimes and who, at least apparently, do not respond to any of the questionable power structures that have managed the Armed Forces for decades. Local media have also reported that Petro’s interest is to promote more women to the leadership.

The result is that, at the moment, the National Police, an entity that Petro wants to remove from the Ministry of Defense, has only eight generals to lead almost 200,000 members.

“Removing up to 70 generals and colonels, although many of them are not guilty (of crimes) or are under investigation, and also having placed two members of his old guerrilla in key institutions (intelligence and protection of victims), carries a very strong message. the military and complicates what is to come,” says Marulanda, referring to the appointments of two former members of the M19, the guerrilla to which Petro belonged in the 1970s.

Following the attack on the police on Friday, Petro announced that some 2,000 troops, almost a quarter of the total, will be relocated to less violent parts of the country.

image source, Getty Images

Since Petro came to power there have been 11 of the 72 massacres that have occurred this year.

2. Limit bombing

Minister Velásquez announced last week that a crucial operation in the strategy that the military has used to confront illegal armed groups will be reformulated: bombing.

The minister’s goal is to prevent civilians from dying in attacks on suspected guerrilla members. Specifically children, who are often forcibly recruited and used as a shield.

A report by the Institute of Legal Medicine estimates that in one in three bombings have killed minors During the last years.

“Recruited minors are victims,” Velásquez told a news conference. “Therefore, any military action once morest illegal organizations cannot endanger the lives of these victims of violence,” he said.

The measure shows concern for human rights. The army explained that the bombings will not stop, but they will have new protocols. However, experts say that in the military mentality it is not seen that way: for them it is normal that there is collateral damage and they consider bombing as the most effective weapon to corner the guerrillas. Historic leaders of the FARC—Alfonso Cano, Raúl Reyes, and Mono Jojoy—died in air strikes.

image source, Getty Images

The foreign minister, Álvaro Leyva, has already started talks with the ELN in Cuba to resume negotiations for peace with the largest current guerrilla group.

3. Reform of the riot squad

The new government has also said that it intends to reform —but not eliminate, as some are asking— the Mobile Police Riot Squad (ESMAD), the body prepared to contain social protests.

During the social unrest of 2019 and 2021, the ESMAD was questioned for the improper use of force and for having caused the death of dozens of protesters. The UN held police responsible for 28 deaths in the 2021 protests.

Some experts at the time explained that the body responded to the logic of the armed conflict, where every dissident in the system was seen as an insurgent, and that was why it was necessary to reform the entity with more civil than military guidelines for the post-conflict.

The new Police Director, General Henry Sanabriagave some clues of what the reform might be: colors less intimidating than black in the uniforms of the agents, tanks converted into ambulances and a new name for the body, Unit for Dialogue and Accompaniment to the Public Demonstration.

“There has to be a change, of course clarifying that every police force requires a force that can contain a demonstration that turns violent,” Sanabria said.

An internal statement from the Armed Forces leaked this week to the media outlet “La Silla Vacía” assured that the Damascus doctrine will be implemented, a civilian code of conduct for the institution devised by President Juan Manuel Santos following the signing of peace with the FARC .

image source, Getty Images

Although it is for riots, the Esmad is considered an entity designed under the logic of conflict. And that is why Petro wants to reform it.

4. End forced coca eradication

Another policy that might be a substantial difference between Petro and previous governments has to do with drug trafficking, a problem that has historically been addressed from the areas of Security and Defense in alliance with the United States.

“Peace is possible if the policy once morest drugs seen as a war is changed for a policy of strong consumption prevention in developed societies,” Petro said in his inaugural speech on August 7.

What looks like a health policy is, however, a change in the military fieldbecause the suspension of the forced eradication programs for coca crops and of the studies to resume aerial spraying of plantations with glyphosate was announced.

Both are policies that contrast with the government of Ivan Dukewhich was generally more in tune with most military guidelines.

Petro, however, said that “suspending aerial fumigation for illicit crops is not permission to plant more coca plants.”

“The PNIS (illicit crop substitution system) must be implemented immediately, along with land substitution, and agro-industrialization projects for licit crops owned by the peasantry,” assured the president.

Beyond the convenience or not of these new measures, experts are skeptical regarding how they have been announced, the absence of prior dialogue with the military sector and, above all, the lack of a plan that allows understanding how all these novelties are articulated. initiatives. Violence in the country, meanwhile, continues to escalate.

Mantilla, from the Fundación Ideas para la Paz, concludes: “If Petro fails to quickly adopt a clear security policy accompanied by differentiated territorial intervention plans in which the Public Force has a specific role, his good intentions would only be good. intentions”.