- John McManus

- BBC News

3 hours ago

There is a complex debate regarding whether any kind of depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, even the most respectful, is forbidden in Islam. For most Muslims, it is beyond question; It is not permissible to draw any picture of the Prophet Muhammad, or any other prophet in any way.

As most Muslims believe, images and statues encourage polytheism and idolatry, and this is indisputable.

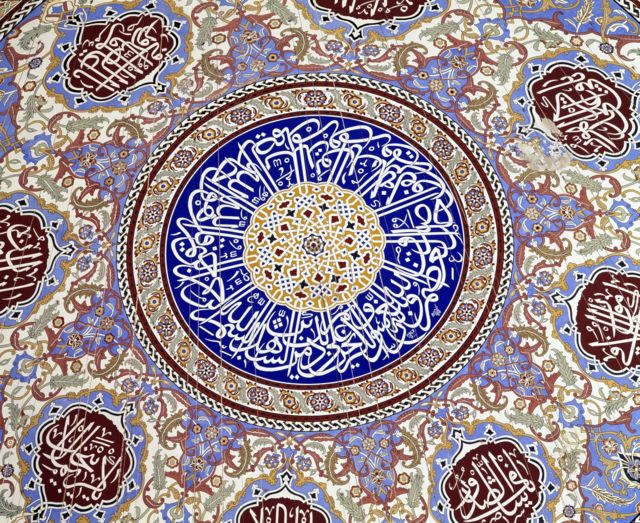

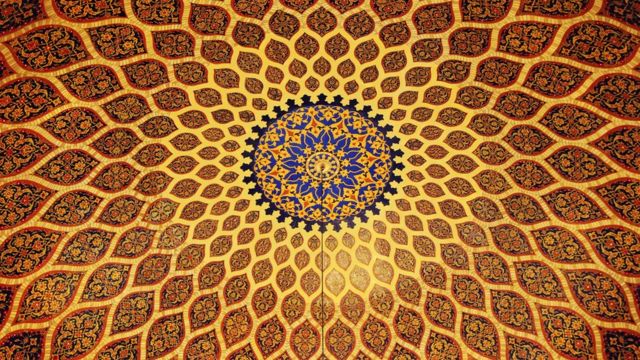

Back in history, Islamic art has always been dominated by geometric ornamental patterns, repetitive and interlaced motifs, or calligraphy, rather than figurative art.

Muslims refer to a Quranic verse from Surat “The Prophets” where the Prophet Abraham addresses his father and his people, in which he said: “When he said to his father and his people, What are these statues to which you are devoted? They said: We found our fathers worshiping them. He said: You and your fathers were in clear error.”

However, there is no ruling in the Qur’an that expressly forbids the personification of the Prophet in images and statues, according to Mona Seddiqi, a professor at the University of Edinburgh. Instead, she argues, the idea arose from the Prophet’s biography and sayings, collected in the years following his death.

Siddiqui refers to pictures of the Prophet Muhammad, painted by Muslim artists, from the Mughal and Ottoman Empires. Although the features of the Prophet’s face were hidden in some of them, it was clear that they depicted him.

She says that the pictures were drawn out of devotion and reverence: “Most of those who drew these pictures did so out of love and reverence, not with the intention of idolatry.”

So, at what stage was depiction of the Prophet Muhammad forbidden?

Christian Gruber, associate professor of Islamic art at the University of Michigan, says that many depictions of the Prophet Muhammad dating back to the 13th century CE, were presented exclusively and privately only to avoid idolatry. “They were considered valuable pieces and probably displayed in elite bookshops.” She added that these pieces included miniatures depicting Islamic figures of special status.

Gruber says the emergence of mass print media in the 18th century presented a challenge. The European powers that colonized some Islamic countries and spread their ideas there, also left an impact.

Gruber argues that the Islamic response came by emphasizing how different Islam is from Christianity, which has historically been marked by the proliferation of icons.

Images of the Prophet Muhammad began to disappear, and a new discourse emerged once morest his portrayal or depiction, according to Gruber.

But Imam Qari Asim, from the Leeds Makkah Mosque, one of the largest mosques in the United Kingdom, denies that there has been a major change, and asserts that the hadiths forbidding depictions of living creatures automatically mean the prohibition of depicting the Prophet Muhammad.

He says the Middle Ages must be understood in its context. “Most of these images relate to the night of the Night Journey and the Ascension to Paradise, in which something like a horse (Al-Buraq) was mentioned, and that the Prophet was riding it or something like that.

“The ancient religious scholars strongly condemned these images as well, but they do exist,” he adds.

Asim believes that the main point is that they are simply not personal pictures of the Prophet Muhammad, and that the subject of many of the pictures is not clear, and there is also a question as to whether all these drawings are in fact intended to depict the Prophet, or a close companion to him participating in the same scene.

That has changed, says Professor Hugh Goddard of the Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World at the University of Edinburgh.

And he continues, “there is no consensus in any of the primary sources, the Qur’an and the hadiths of the Prophet.”

“The Islamic community in a more recent period tends to have different views on this issue, as well as other issues,” he adds.

He says that Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the religious scholar whose teachings paved the way for Wahhabism – the dominant form of Sunni Islam in Saudi Arabia – was a key figure.

“The controversy has become more and more intense – especially associated with the Wahhabi movement, there is no doubt regarding any reverence other than God’s, including the Prophet.”

“There has definitely been a big change over the last 200 years, maybe 300 years,” he says.

Goddard points out that the situation is different for sculpture or any other form of three-dimensional representation, where the taboo has always been more pronounced.

For some Muslims, my friend says, the aversion to photography has extended to a refusal to put pictures of any living creature – humans or animals – in their homes.

Do Shiite Muslims also forbid the embodiment of the prophets?

The issue of the prohibition of photography did not extend to everywhere, and many Shiite Muslims seem to have a slightly different view.

Some modern images of the Prophet Muhammad still exist in parts of the Islamic world, says Hassan Yousefi Eshkafari, a former Iranian cleric who now resides in Germany.

Eshkafari told the BBC that recent pictures of the Prophet Muhammad decorate many homes in Iran, adding: “From a religious point of view, these pictures are not forbidden, they are found in stores as well as in homes. They are not seen as offensive, not from the point of view of neither religious nor cultural.

The differences between the two traditional Islamic sects can always be seen; Sunni and Shiite.

But Gruber says that those who claim that the prohibition was in place from the beginning, are mistaken.

But it is an argument that is not accepted by many Muslims.

Dr. Azzam al-Tamimi, former head of the Institute of Islamic Political Thought, tells the BBC that the Qur’an itself does not state anything of the sort, but all Islamic references agree that the Prophet of Islam and other prophets cannot be embodied in images, statues or any other kind of kinds of arts, because, according to Islamic belief, they are infallible personalities, role models, and therefore they should not be presented in any way that might cause them to be disrespected.”

He is not convinced by the argument that if there were drawings depicting the figure of the Prophet Muhammad in the Middle Ages, this indicates that there was no absolute prohibition, and says “even if they existed, they would be condemned by Muslim religious scholars”.