That day, the Grim Reaper arrived riding a horse and carriage. It was him April 19, 1906 in Paris and the weather, lousy, did not bode well for Pierre Curie. That morning, the pioneer in the study of radioactivity trudged up Dauphine Street. He wasn’t in his best form: slow from a rheumatic weakness, he hinted at trouble moving. To make matters worse, the annoying drizzle that covered the capital had caused puddles to proliferate along the sidewalks. A lousy day to walk, go.

For Pierre, the end awaited him on the other side of any sidewalk. Crossing the street, a ‘truck’ – as it was then called

to the carriages- ran over him. The pain prevented him from escaping and the water made him slip. A lethal cocktail that caused the vehicle, loaded to the poop with military material, will go over your skull and spill his brains through the streets of Paris. “The accident was trivial, idiotic, and produces a deep sense of sadness in the scientific world. The admirable and modest sage who discovered the secrets of radium did not deserve that tragic end, “explained ‘Whisky’, the ABC correspondent in France.

Three and a half hours following that madness, Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie received the news of the sad death of her husband. She affected him so much that she treasured her clothes with brain scraps in her closet. Although, in the end, she burned it. «Pierre sleeps his last sleep under the ground; it’s all over, it’s all over, it’s all over… I don’t see anything that can console me, except perhaps scientific work, and not even that because, if I do it successfully, I won’t bear not being able to share it,” the widow wrote in her newspaper. From then on, and for a few months, everything stopped in the life of the scientist. It was a blow to her jaw.

But nevertheless, the Curie lady managed to overcome that harsh setback of fate. Not only that, but she far surpassed the work that she had carried out with Pierre and she became one of the most renowned scientists in history. Barely five years later, she alone obtained the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for having isolated the metallic radium and became the only person to win that award twice. In addition, her knowledge helped save hundreds of lives in the First World War; something that tends to tiptoe through the great History manuals (with a capital H). And so she continued until she left this world in 1934 due to aplastic anemia.

Tragic childhood and harsh adulthood

That was not the only tragedy in Maria’s life. Rather the opposite. Hers was an existence accompanied by pain from the moment in which Poland saw her birth on November 7, 1867. His biographers say that he spent his young years in the shadow of a family that did not know how to show him affection. It didn’t take him long, moreover, to see his mother leave – who had died of tuberculosis – and one of his sisters. “You had to take pensioners. One of them fell ill with typhoid fever, infecting Sophie already Bronia. Bronia cured. Zosia, weaker, succumbed to fever. Death entered the house », Eva, daughter of the scientist, wrote in a work dedicated to her mother.

What cannot be denied is that he was brilliant. She was in elementary school, in high school and in all those aspects of life that he focused on. To such an extent that she soon became a governess for wealthy families. Warsaw was the city in which she worked the longest until, by twists of fate, she decided to change the scene and travel to ‘la France’. “My dear, you need to do something for your life. If you collect a few hundred rubles this year, next year you can come to Paris and live with us, where you will have a bed and food », offered her sister Bronia through a long letter.

Maria traveled to France at the end of 1891 with the goal in mind of having higher studies in science, something that Poland did not allow women. Shortly therefollowing she enrolled in the sorbonne as ‘Mary’. It was the first of an infinite list of times that he would sign that name. “With the little money that she collected, ruble by ruble, she was entitled to listen to the classes she liked and to use the experiment room,” her daughter wrote. From then on, college was her only goal in life. Hunger, anemia and lack of liquidity they were not too troublesome a stumbling block and he graduated in Physics in 1895 and in mathematics a year later. Almost nothing.

The letters he wrote to his family in those years clearly demonstrate the shortcomings he suffered: «Brother, I have already rented a room that suits me, on the sixth floor and on a clean and decent street. It has a window that closes well and, when I have fixed the room, it will not be cold in it, since it is not bricked and has a wooden floor. Compared to my room last year, it’s a real palace.” Shortly followingwards he insisted that he had already installed his furniture: “What he pompously calls that is nothing more than a set worth not twenty francs.” But nothing would stop her until she reached her ultimate goal.

bittersweet years

Although he graduated in 1895, it was a few months before when his life took a turn. In 1894, Marie met Pierre, also a physicist. He became her better half following walking down the aisle and completed her personally and professionally. «The first days they entertained like children. They bought two bicycles and two raincoats because the summer was rainy, and they went out every day to walk along the roads”, explained Eva. Although where they had the most fun was in the laboratory, where they collaborated hand in hand for years and where the radiation maiden won many awards.

«Two degrees, a university aggregation contest and a study on the magnetization of tempered steels, such was the balance of his activity until 1897», highlighted his daughter.

It was in their laboratory, built improvised in their house, where they began to study the phenomenon that made them famous: the natural radioactivity. They stumbled across it by chance following reading previous research from Antoine Henri Becquerel, but they achieved something much greater…discovering two new elements. The first was radium, with atomic number 88 on the periodic table; the second, polonium, named in this guise in honor of the country that had seen Marie born. “The couple looked for the new element in pernblende, which in its raw state has been shown to be four times more radioactive than pure uranium oxide,” revealed her daughter.

The one and the other, the other and the one, refused to patent their discovery so that science might investigate it further. And it didn’t go bad for them. In 1903, both shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Becquerel for his research and discoveries, something that the magazine Blanco y Negro narrated in this guise:

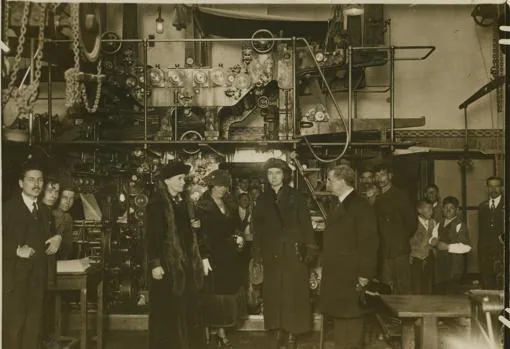

«There you have a couple of truly wise men, who are the heroes of the day and even of the year and perhaps of the century: that lady who is driving a strange device is Madam Curie, and next to her, in the front row, Monsieur Curie. Both are the discoverers of radium, the new simple body that is worth exactly three thousand times its light and heat without diminishing its volume or weight in the least; that launches invisible rays of three kinds, some beneficial ones that serve to cure lupus and kill various kinds of microbes and to prolong life and even to create new species, according to Mr. Curie. With the light of the radium, one can see through the bones of the skull and study the work of the brain in vivo».

Pierre’s death was both a brake and a boost for Marie. She was initially in ‘shock’. However, she knew how to overcome and continue with her projects. Around 1910 she obtained a chair in physics at the Sorbonne university; the one that her husband had set free. Thus, she became the first woman to teach there. Of course, she was the director of the new Radium Institute. His studies in the field of X-Rays were also key in many fields of medicine. Thus, it is not surprising that he won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1911.

Without having made a profit despite being a pioneer, in the First World War it acquired portable X-ray machines and created several radiological ambulances. Because little of her was, following the conflict she became the director of the Radiology Service of the French Red Cross. She died in 1934 from an illness caused by the same radioactive elements she had studied for years. sad irony.