2024-04-24 13:39:00

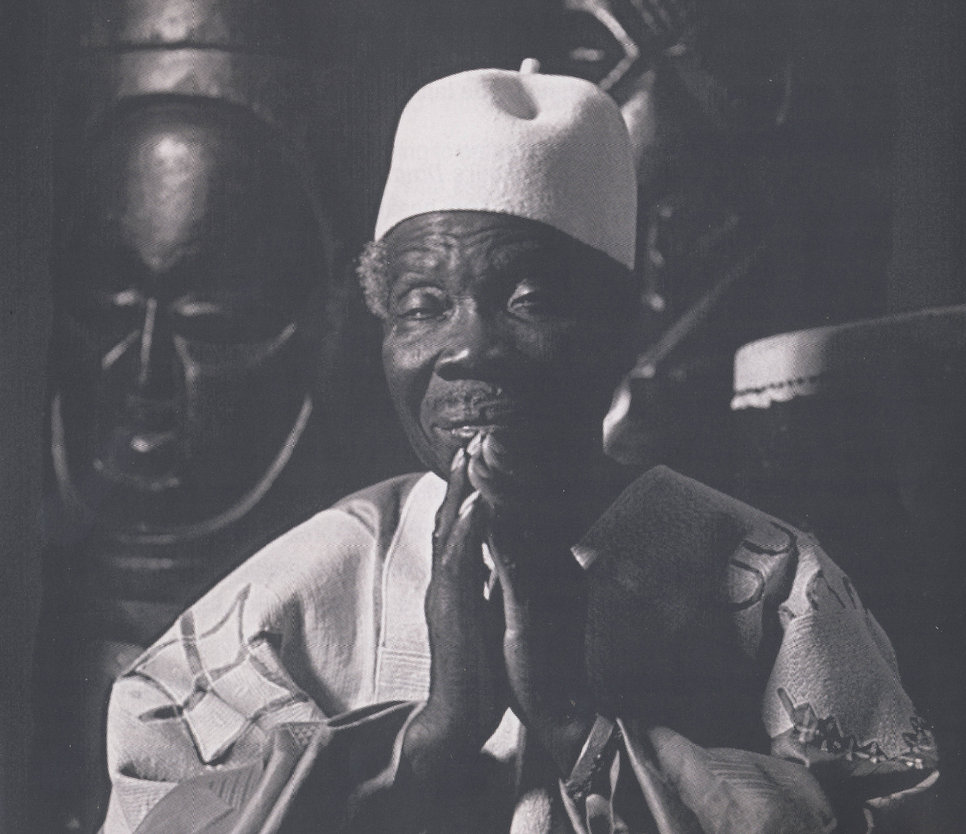

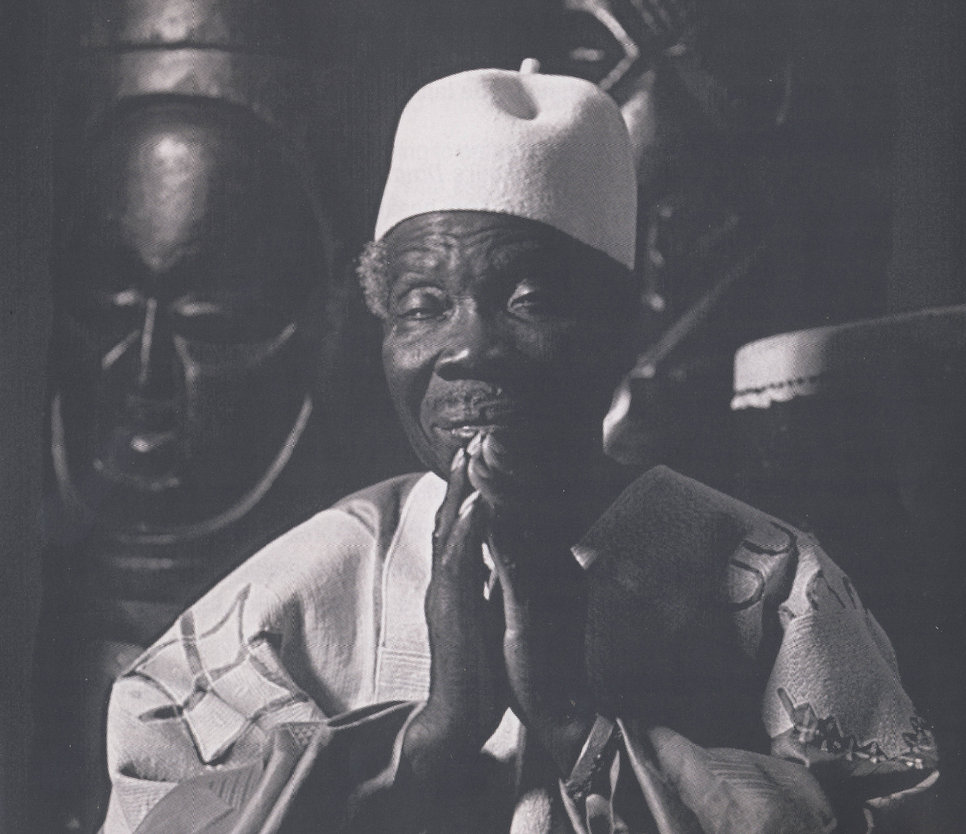

A percussion master, educator and fervent Pan-Africanist, Olatunji has influenced just regarding everyone in the United States where he calls home, from John Coltrane to Spike Lee, while in Europe, it’s another great artist, Serge Gainsbourg, who “borrowed” Babatunde’s rhythms for his album Gainsbourg Percussionreleased in 1964. In his autobiography published posthumously, the percussionist explains that the art of drumming is “a very special kind of trinity” made up of the spirit of the tree from which the barrel is cut, of the vital force of the animal whose leather becomes the skin of the drum, and of the own spirit of the person who hits it. Three elements which, together, produce “an irresistible force” and provide “the balance that gives the drum its healing power”. Let us return to the life of Olatunji in a trinity of acts, like so many tributes paid to the artist.

The village kid

Olatunji’s story is worthy of Homer’s, nothing less. Born in 1927 in the small fishing village of Ajido, regarding sixty kilometers from Lagos, he was given the name Babatunde, which means “the father has returned”, because he was born barely two months following the death of his father, who was on his way to becoming the leader of the community. While those close to him hoped that he would take his father’s place, it was ultimately his mother, a potter by profession, who would determine the child’s path.

In his book The Beat of My DrumBabatunde says: “There was no percussion school, but any kid in the village is in contact with drums, dances and songs… I went further, because I decided to follow the players drumming wherever they went. They went from market to market, from village to village, and I didn’t let them go. » Aware of her son’s passion, Babatunde’s mother made him his first drum, a clay instrument called an “apesin”, and his destiny was sealed from then on.

As a teenager, he settled in the federal capital and continued his musical training within the Methodist Church, where he was hired as a chorister and accompanist. Young adult in the capital, it was by chance that he came across the magazine Reader’s Digest on an article mentioning a scholarship at the Morehouse Liberal College of The Arts of Atlanta, a “traditionally black university” [Historically Black Colleges and Universities – HBCU; NdT], to which he submits an application. Following his admission, he left Nigeria for the United States in 1950.

The Pan-African

“They had no idea regarding Africa”, Babatunde wrote regarding this time. Aware of the need to educate his peers within Morehouse, Olatunji laments, having considered a career as a diplomat before leaving Nigeria: “Africa had contributed so much to world culture, and yet they knew nothing regarding it. I would invite them into my room and we would talk regarding their African heritage. » Forming a drum and dance troupe, he began leading school programs on African performing arts. And now the transmission of the practice of drumming, which would become a life’s work, begins in earnest.

Elected president of the All-African Students’ Union of the Americashe participates in the All African People’s Conference in Accra in 1958, where he rubbed shoulders with no less than WEB DuBois, Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba. The same year, he came into contact with the arranger of Radio City Music Hall, Raymond White, who invited him to collaborate on a show given in this famous music hall in New York. Their African Drum Fantasy would be shown four times a day for seven weeks, and it was during one of these performances that Babatunde was spotted by Al Han, then head of Columbia Records.

Han immediately signed a contract with the young percussionist and thus began Babatunde’s “Year of Africa” with the release in February 1960 of his first album, Drums of Passion, at Columbia Records. With Babatunde’s arrangements for ensemble of drummers and voices, this glorious stereo recording features a song of praise to the orisha Shango performed on the transatlantic bell motif, extended version, which will inspire many jazz drummers such as ‘Elvin Jones and Art Blakey.

The album also includes the song “Jin-Go-Lo-Ba”, which deserves careful attention. Rhythmic conversation between the mother drum (yes ilu) and the baby drum (representative) which highlights a very catchy song in the form of a question and answer, “Jin-Go Lo-Ba” will be “borrowed” by Serge Gainsbourg four years later for his record Gainsbourg Percussion, hidden under the title “Marregarding”. Gainsbourg also covered some of the “Kiyakiya” and “Akiwowo” interpolations from Drums of Passion as well as certain elements of the “Umqokozo” of Miriam Makeba. Unfortunately, this premature sampling was carried out without the authorization of the authors, and Babatunde will never be credited. In 1969, it was the turn of the Latin rock group Santana to cover “Jin-Go-La-Ba” renamed “Jingo” on their first eponymous album, where we discovered that Carlos Santana was cited as songwriter, although the song was composed entirely around the musical riff of Babatunde’s track.

Nevertheless, Drums of Passion will sell five million copies and will even gain, in 2004, registration in the National Recording Registryarchives of recordings considered to be “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant and/or documenting or reflecting life in the United States”an institution in which the rhythms of Babatunde are preserved alongside the text of the speech « I have a dream » by Martin Luther King in 1963. With the release of Drums of PassionBabatunde officially went “hip” and began a historic career as a sideman (often credited as Michael Olatunji) on records by figures as varied as Cannonball Adderley, Horace Silver and Max Roach.

Babatunde became a regular at the legendary Birdland, a jazz club in New York, where he opened for jazz greats such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Quincy Jones. “We were playing Afro-jazz long before anyone used the term”Babatunde would later point out, and it was also in this same Birdland Club that he became friends with the saxophonist John Coltrane. In 1965, Babatunde and Coltrane created the Olatunji Center for African Culture [Centre Olatunji pour la Culture Africaine], with the aim of offering music and dance lessons to children in the New York neighborhood. John Coltrane even gave his very last concert there in April 1967, three months before his premature death, alongside his wife Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders.

Wool

During the last decades of the 20th century, Babatunde would lead his own troupe, “Drums of Passion” composed of his students, his daughter Modupe and seven of his grandchildren. It has continued to be popular, as evidenced by filmmaker Spike Lee’s decision in 1986 to include Olatunji’s song “Mystery of Love”, dated 1962, in his first film. She’s Gotta Have It. Olatunji also collaborated with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart on his album Planet Drumwinner of a Grammy Award in 1991 in the category of “Best World Music Album”, the year in which the North American institution inaugurated this musical category.

In addition to teaching percussion in person, Babatunde became a teacher on VHS, and published the educational video in 1993 Babatunde Olatunji: African Drummingin which he reveals the secret of his phonetic method “gun, go do, don’t”. Returning to the very accessible nature of his teaching method, Babatunde declared, in all modesty: “It’s been there all along!” It comes from the consonants of the Yoruba language. I didn’t invent this system, I just discovered it. » Indeed, Olatunji has been a devoted ambassador of the Yoruba language all his life.

“Anyone who does something so great that he or she can never be forgotten automatically becomes an Orisha”, he said in his autobiography. Babatunde himself entered the followinglife on April 6, 2003, just a day before his 76th birthday. Two years earlier, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame from Percussive Arts Societyalongside Baby Dodds, pioneer of New Orleans drummers, and Avedis Zildjian, Armenian manufacturer of world-renowned cymbals. His legacy as an educator continues to be passed on.

Let’s leave Babatunde with the last words, those he chose to define his concept of the drum circle as a sacred ensemble: “I am the drum, you are the drum and we are the drum. Because our entire world responds to a rhythm, and everything we do in life follows a rhythm. »

1714058198

#life #legacy #Babatunde #Olatunji