It was one of the large Chilean business groups in the ’90s and ‘2000s, formerly a Corpgroup shareholder and the first bank holding company to install a flag in the United States. But ten years ago her influence began to wane, along with the success of her business (see sidebar).

Today, in Chile, little is known regarding the Rishmague family. But that, only here, because an unknown conflict arose in the United States that splashed one of its most iconic companies and put them back in the eye of the hurricane.

Last year computers at the US Market Abuse Unit (MAU) Analysis and Detection Center – which goes following suspicious employers in the financial industry – received a rare alert that targeted two companies: UCB Financial Advisers Inc and UCB Financial Services Limited, both companies indirectly linked to Union Credit Bank (UCB), the first bank of Chilean origin in Miami (which is no longer in operation). Said message stated, in simple terms, that unusual movements had occurred in the accounts of some clients in said financial institutions.

With this, the chips of MAU and the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) moved fast. The first inquiries were carried out by the official Jeffrey Oraker, in conjunction with Danielle Voorhees and Joseph Sansone, all members of the SEC and experts in market abuse. In June 2021, the entity from the northern country filed a lawsuit once morest UCB Financial Advisers Inc, UCB Financial Services Limited and Ramiro Sugranes, one of the Rishmague partners in the United States, before the Florida federal court.

According to the North American entity – in charge of protecting investors and maintaining the integrity of the stock markets – Sugranes “participated in a long-lasting fraudulent operations allocation scheme, commonly known as ‘cherry picking'”, through the companies UCB Financial Advisers Inc and UCB Financial Services Limited. With this, he is accused of transferring money to his parents.

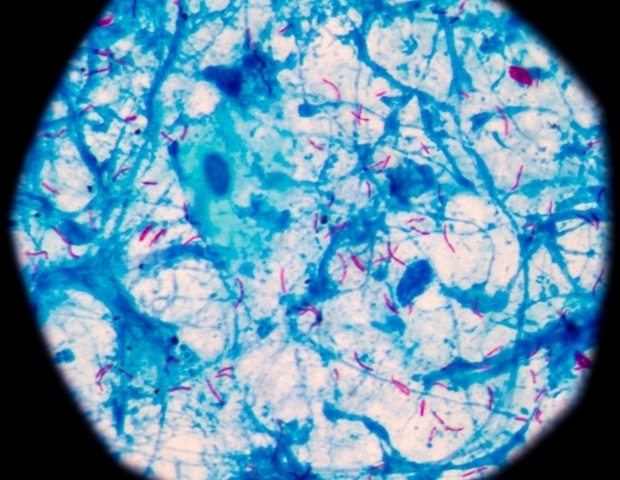

Cherry picking, in American financial jargonis a complex fraud to locate and practically invisible to human supervision. That is why the SEC relies on specialized software to detect suspicious movements.

In particular, this crime is generated when stockbrokers “select” investments by looking at the performance of their trades throughout the day and stick with the best-performing stocks. “This allows brokers to enjoy the benefits of trading without risk, while their investors suffer unfair losses,” explains the specialized law firm Kurta Law on its website.

Specifically, according to the SECthe defendants assigned “thousands of profitable trades of more than $4 million in shares to two preferred accounts maintained in the UCB companies in the name of Ramiro Sugranes Hernández and Thelma Lanzas, the parents of Sugranes”.

And in addition, the Rishmague partner would have assigned “millions of dollars of unprofitable operations to other customer accounts”, which would have generated economic damage of approximately US$ 4.6 million to dozens of users.

The formula

To understand what the SEC accused, it is essential to know Ramiro Sugranes (58), a shareholder of UCB Advisers and according to his LinkedIn, still executive director of UCB Group, the holding company that brings together the investments of the Rishmagues in Chile and abroad. He is a Nicaraguan citizen but has lived for decades in Miami, and has historically been linked to the companies of the national family.

According to the legal action, the UCB group entities had 100 clients from the United States (with addresses in New York, Florida, Texas and Minnesota), Colombia, Nicaragua and Chile. Since September 2015, Sugranes and his partner (Lina Garcia, who was a senior vice president at UCB Group and who also appears in the SEC’s complaint) fraudulently assigned thousands of trades “to carry out their deceptive selection plan.”

Before understanding the methodology, it is essential to know the characteristics of “options”, a contract to buy or sell a security in the future at a certain price and that UCB offered. Many advanced investors prefer this instrument to limit risk to a certain amount.

According to data collected by the SEC, Sugranes used the credentials of Lina García to carry out the “cherry picking”. What was he doing? According to the regulator, they diverted stock market operations with positive profits to “own” accounts. In this case, from his parents.

So, “if the position increased in value during that day, it would typically be sold or closed, thus locking in the profit,” the lawsuit explains. Then, this utility was assigned to the preferred account, which was in the name of Sugranes’ parents. In the opposite case, if the position decreased in value (and therefore suffered a loss), it was artificially assigned to one or more of the non-preferred accounts, that is, of other clients of the company.

During that time, 1,600 stock market operations -95% of them profitable- were placed in the preferred accounts “generating profits -on the first day- of US$ 3.9 million.” In this same period, 1,400 operations were located in non-preferred accounts but with a return of 32%. This generated losses of US$ 4.6 million for customers.

The agreement with the SEC

A little over a year following the filing of the lawsuit, and without having accepted or denied the charges filed by the SEC, the defendants decided to reach an agreement with the North American agency. “(Sugranes and the UCB entities) consented to a final judgment being issued that would permanently prohibit them from violating the anti-fraud provisions,” the US regulator explained.

Part of the agreement was as follows: that Sugranes pay restitution for US$4.6 million “partially jointly and severally with the other parties, with prejudice interest, and a civil penalty of US$500,000.” On behalf of UCB Financial Advisers Inc and UCB Financial Services Limited, it was agreed to pay a civil penalty of US$250,000 each.

In addition, on October 24, the SEC initiated an administrative proceeding that prohibits Ramiro Sugranes from associating “with any broker, stockbroker, investment advisor, municipal securities dealer, municipal advisor, transfer agent, or statistical rating organization recognized to Nacional level”.

This directly interferes in the business of both Rishmague family companies, which, says an insider, will be “deeply affected” by the explosion of the case.

This same source believes that, despite the fact that Sugranes was a close executive, the Rishmague family claims that they were not aware of the fraud committed.

And despite having been a diversified economic group and with successful investments in various latitudes (banks, finance companies, construction companies, health centers, sports clubs), today UCB Group is minimizing its bets and is cutting staff. Its offices in Santiago are being leased and the few remaining workers are teleworking.

DF MAS communicated by telephone with senior executives of the group, who responded that the family did not want to issue statements.

The Ten Mosques

History says that in 1964 the businessman Odde Rishmague -22 years old at the time- arrived in the United States with 6 thousand dollars under his arm, accompanied by his wife (Edith Piddo) and his son Miguel, just one year old. He had one thing in mind: achieving the “American dream”, as he declared to the Chilean media. And he did it. This, thanks to a series of investments. One of them was the Rishmague Tire Company, a firm focused on producing raw materials for the manufacture of tires, which was sold to Goodyear in 1988.

In 1986, following receiving an invitation from businessman Carlos Abumohor, he returned to Chile to buy, along with other Chilean businessmen of Arab origin -such as Espir Aguad, Salomón Díaz, Alberto Kassis, Jorge Selume, Álvaro Saieh, Fernando Abuhadba, among others-, Banco Osorno and La Union. It was an operation that gave rise to what later became known as “The Ten Mosques”, a group of high-net-worth families that later diversified their businesses, especially in the financial, industrial, retail and agricultural sectors. Ten years later, in 1996, Banco Osorno was sold to Banco Santander for US$495 million.

In that same decade, some members of Las Diez Mezquitas founded Infinsa, a holding company that invested in a series of firms in the financial sector (including banks Concepción and Buci, from Argentina). In 1997 the company was renamed CorpGroup. Rishmague came to have 24.5% together with the Díaz and Awad families, ceding control to Álvaro Saieh.

At the end of the 1990s, Odde Rishmague planned his next big project, but this time as an independent: Union Credit Bank (UCB), the first Chilean bank to set foot in the United States. He did the paperwork and in eight months he obtained the license to operate in Florida. He opened his first branch in the late 2000s in Brickell, the financial district of Miami. It began operating in October 2001, weeks following the attack on the Twin Towers.

The business did well. They expanded it to Central America and then to Brazil, received recognition from the United Nations and continued to open branches in Miami. One of the obstacles was the subprime crisis, which allowed them to turn around the business. They got partners and planned their “second chapter,” says an insider.

“We are in a position to acquire one of the banks that are in the hands of the government. We are at it, because now we have too much capital. We can increase our size by almost three times with the capital we have,” Miguel Rishmague, Odde’s son, told Diario Financiero in April 2010. Years later, the bank added investors and became Apollo.

Before the subprime crisis, Odde and Miguel commissioned a study from North American economists to outline the “safest” industries to invest in. The result was the medical, gastronomic and financial (non-bank) loan category. With this in mind, they developed Medicenter, a medical branch company that started in Chile and later expanded to Peru and Colombia.

But since 2012 no more has been heard from them. They continued to invest in Chile (here, for example, they are minority shareholders of Palestine), the United States and Central America, but with an extremely low profile. That, until the United States SEC arrived and exposed one of its top executives.