Posted today at 2:17 a.m., updated at 5:10 a.m.

Reserved for our subscribers

InvestigationIn 2017, the Penelope Fillon case highlighted the role of MPs. The wave in motion! made them hope for a better future. But just days before the end of the work of the National Assembly, many are deploring their working conditions.

It’s a modest victory, one that doesn’t make noise but does good. By a letter received in September 2021, Grigori Michel learns that he won at the industrial tribunal. “Dismissal without real and serious cause”, indicates notification of judgment. Approximately 10,000 euros in compensation and damages. Far from what he claimed, but that’s still it. Especially since the ex-boss of the young thirty-year-old did not appeal.

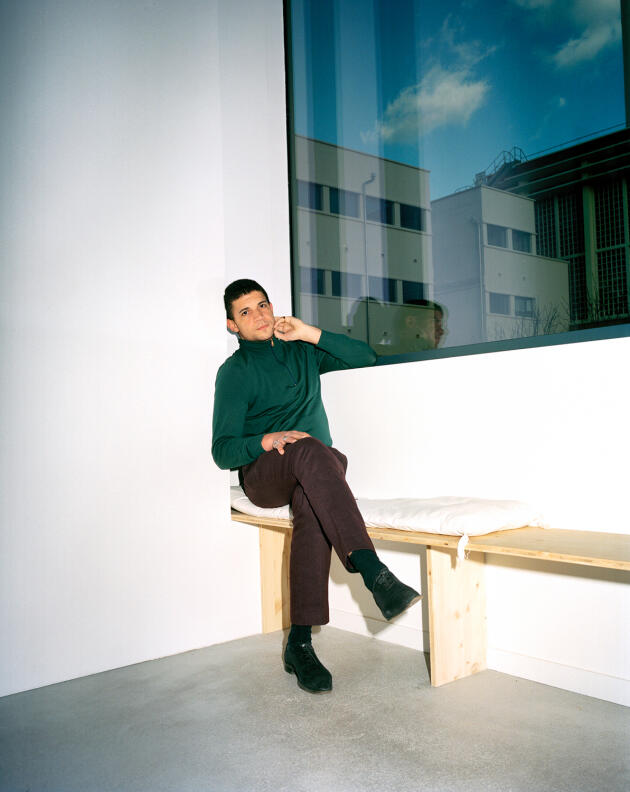

At the beginning of February, in a café on 11e district of Paris, Grigori Michel, round face and short beard, savors: for him, it is the end of an injustice. He claims to have made “Going out for one reason: I opened my mouth when I witnessed my boss sexually assaulting one of my colleagues”. He prefers not to comment on the criminal case, still in progress and in which his former employer denounces “false accusations”.

The boss in question is called Pierre Cabaré. Aged 64, he has been a deputy for Haute-Garonne since 2017, under the label La République en Marche (LRM). Grigori Michel was one of his parliamentary collaborators, from the summer of 2017 to the end of 2018. Now, politics are over, farewell to the dreams of ministerial cabinets, the young man has become an exhibition curator. Of his recent legal success, he did not inform the Palais-Bourbon. “I expect nothing from the National Assembly, he explains. The only thing I wanted was to clear my image and save my honor. »

Unpublished waltz

Emmanuel Macron was elected on the promise of the advent of a “new world”, another way of doing politics. Perhaps less professional, in any case more benevolent. The wave On! had taken everything in its path: the new presidential party had 314 of its candidates elected in June 2017. For the vast majority of novices in politics. Then begins an unprecedented waltz of employees: two-thirds (ie 1,400) lose their jobs. Almost as many arrive at the Palais-Bourbon for the first time, in a world hitherto unknown.

“Each time we highlight professional and legal obligations that are not respected, we are referred to the direct relationship, employee-MP employer. » Mickaël Levy, parliamentary collaborator

A turnover also reinforced by the first law of the five-year term, for confidence in political life, which, among other things, prohibits parliamentarians from employing members of their close family – children, parents, spouses – as assistants. Because, in January 2017, the Fillon affair had thrown a spotlight as unexpected as it was brutal on these great invisibles of parliamentary life, caricatured either in fictitious employment, or in the lumpenproletariat of “little hands” – an expression they hate – compelled to thank you and subject to the moods and schedules of their 577 bosses, the deputies, in the National Assembly or in the constituency.

You have 86.08% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.