The striking photograph above vividly captures the spores of a parasitic “zombie” fungus (Ophiocordyceps) as they spring from a host’s body fly in exquisite detail. No wonder it won the BMC Ecology and Evolution 2022 image competition, featured with eight other winners in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution. The winning images were chosen by the journal’s editor and senior members of the journal’s editorial board. According to the journal, the competition “gives ecologists and evolutionary biologists the opportunity to use their creativity to celebrate their research and the intersection of art and science.”

Roberto García-Roa, an evolutionary biologist and conservation photographer affiliated with the University of Valencia in Spain and Lund University in Sweden, took his award-winning photo while hiking in a Peruvian jungle. The fungus in question belongs to the Cordyceps Family. There are over 400 different species of Cordyceps mushrooms, each targeting a particular species of insect, be it ants, dragonflies, cockroaches, aphids or beetles. Consider Cordyceps an example of nature’s own population control mechanism to maintain the life cycle balance.

archyde news

Selon Garcia-Roa, Ophiocordyceps, like its zombifying relatives, infiltrates the host’s exoskeleton and brain via airborne spores that attach to the host body. Once inside, the spores grow long tendrils called mycelia that eventually reach the brain and release chemicals that turn the unfortunate host into the fungus’ zombie slave. The chemicals force the host to move to the most favorable location for the fungus to thrive and grow. The fungus slowly feeds on the host, sprouting new spores all over the body as a final indignity.

These germs burst and release even more spores into the air, which go on to infect even more unsuspecting hosts – what García-Roa calls “a conquest shaped by thousands of years of evolution” . Board member Christy Anna Hipsley praised García-Roa’s winning photograph for its “depth and composition that simultaneously convey life and death – a matter that transcends time, space and even species.” . The death of the fly gives life to the fungus. »

The winners and runners-up in the individual categories are below.

Winner: Relationships in Nature

This image of a bohemian wax wing (Cottontail chatter) feasting on fermented rowan berries is the work of ecologist Alwin Hardenbol, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Eastern Finland. According to Hardenbol, the birds love the berries so much that they will migrate to where the berries are most abundant, not only in Finland, but also in Western, Eastern or Central Europe. Waxwings can eat twice their own weight in rowan berries in a single day. The birds feed and the berries disperse their seeds.

However, “although this relationship is very beneficial for seed dispersal, it is not without cost to birds,” Hardenbol said. “As the berries become overripe, they begin to ferment and produce ethanol which poisons the waxwings, sometimes causing problems for the birds and even death. Unsurprisingly, Waxwings evolved to have relatively large livers to deal with their involuntary alcoholism.

Finalist: Relationships in Nature

Alexander T. Baugh, a behavioral biologist at Swarthmore College, took this image of a hungry fringe-lipped bat (Trachops cirrhosis) feasting on a male tungara frog (Physalalamus pustulosus) at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. Bats’ hearing is fine-tuned to detect the low-frequency mating calls of frogs, naturally stinging, and sexual selection once morest each other. And if their froggy prey turns out to be of the poisonous variety, the bats’ salivary glands can neutralize toxins from the skin.

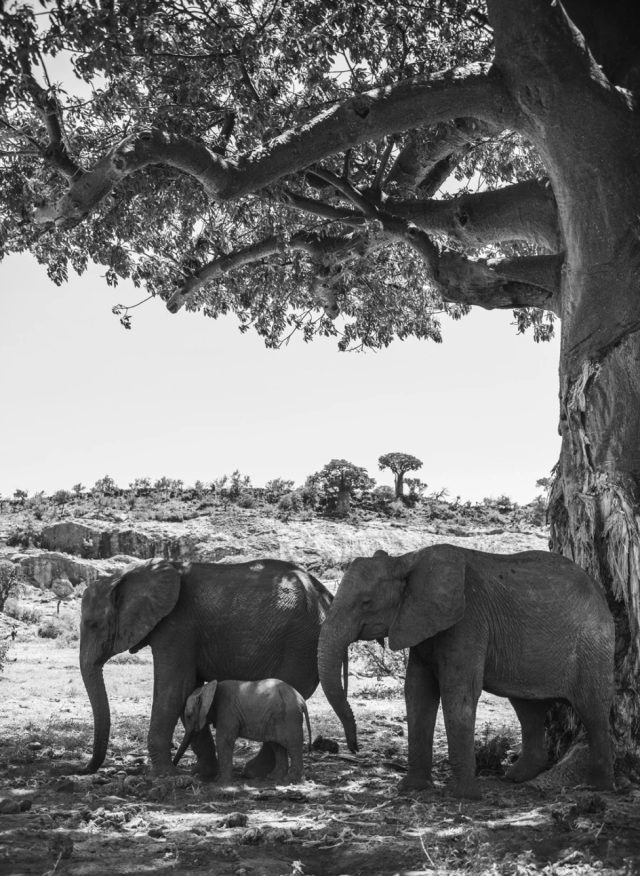

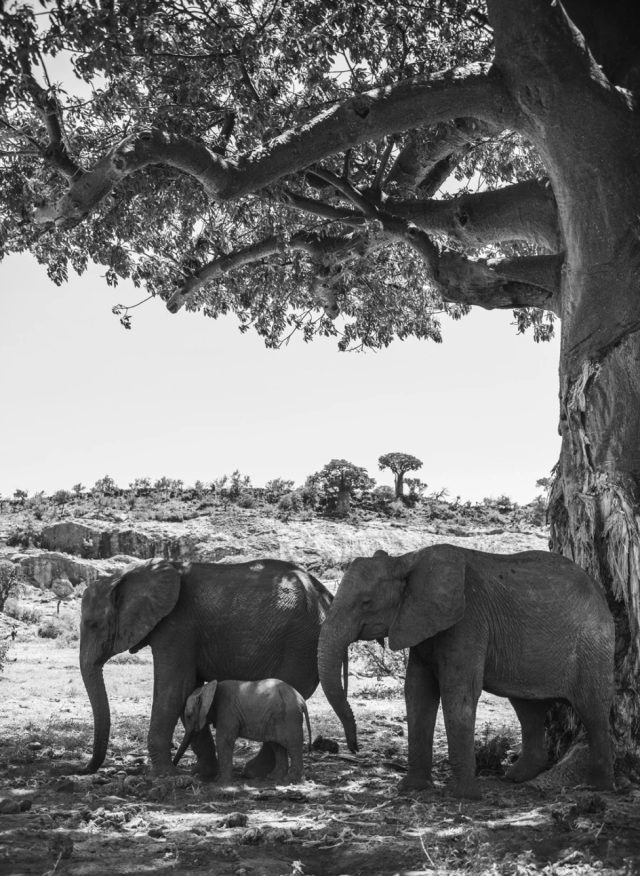

Winner: Biodiversity under threat

Samantha Kreling from the University of Washington captured a trio of African elephants sheltering from the sun under a large baobab tree in Mapungubwe National Park, South Africa. The baobab has evolved to thrive in extremely dry climates by storing water in its trunk whenever drought strikes. Elephants, in turn, can burrow into these trunks to obtain water to drink.

The image shows visible marks where elephants have stripped the bark in search of precious water. Baobab trees have historically healed quickly from this type of damage, but climate change has brought more drought and elephants have stripped the bark faster than trees can heal. The editorial board felt that this image “underscores the need for action to prevent the permanent loss of these iconic trees.”