nusantara’s Shadow: Land Disputes hamper Indonesia’s New Capital

Table of Contents

For Kamarudin, a 62-year-old farmer from Maridan village, East Kalimantan, life revolved around his seven-acre plantation. For decades, his family had cultivated rubber trees, oil palms, and various fruits on land they had owned since 1955, earning a steady $260 USD per month.That changed abruptly when his land was seized for Indonesia’s ambitious new capital city project.

“I was furious when I saw what they’d done,” Kamarudin recalls, his voice heavy with the pain of losing his livelihood. Five months after his plantation was razed, the government offered $63,000 USD in compensation. However, payment for his destroyed crops remains outstanding. “The land bank stole it,” he asserts, holding up a 2017 land certificate proving his family’s long-standing ownership.

Kamarudin’s case underscores a critical challenge facing Indonesia: the delicate balance between large-scale advancement and the rights of local communities. His story serves as a stark illustration of the tensions inherent in such projects. The government agency responsible wields the power of eminent domain, allowing land acquisition for public works even without the owner’s consent, provided fair compensation is given.

In East Kalimantan, this agency oversees more than 4,000 hectares slated for redevelopment as part of Nusantara, the new capital city. This $35 billion project,initiated by former President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo,aims to alleviate Jakarta’s overcrowding and environmental woes,envisioning a sustainable,technologically advanced metropolis.

Spanning 260,000 hectares of Borneo,Nusantara is projected to house 1.9 million people by 2045. While infrastructure development—roads,bridges,and government buildings—is progressing rapidly,notable obstacles remain. Land disputes, funding issues, and environmental concerns surrounding borneo’s unique biodiversity continue to threaten the project’s timeline and ultimate success.

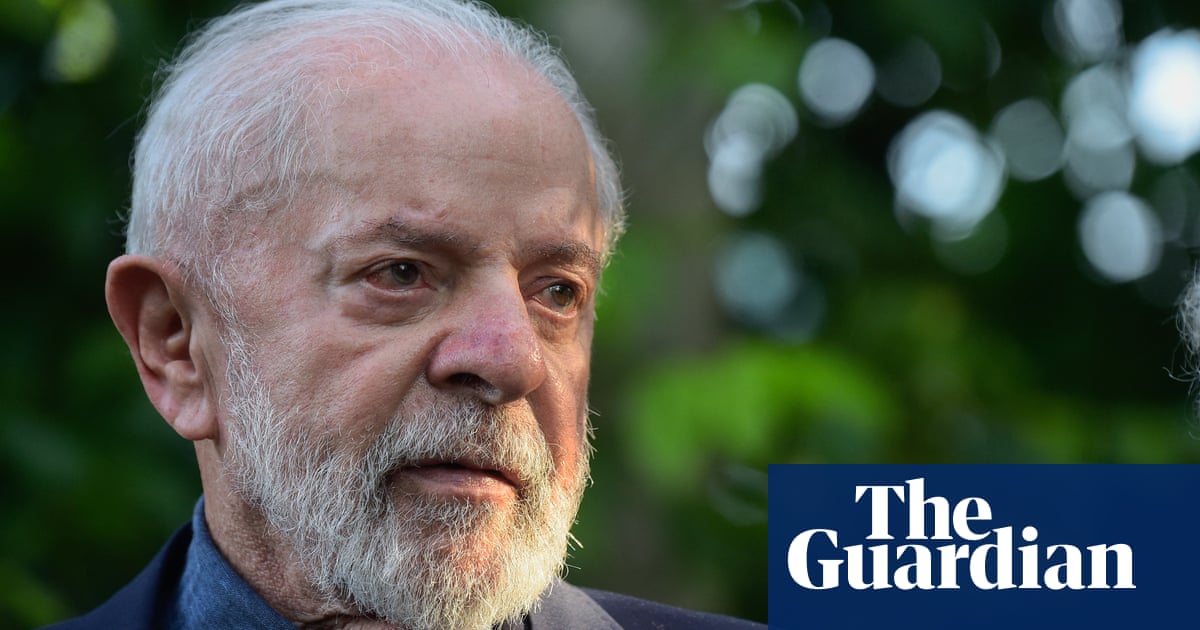

Nataatmadja, head of the National Land Agency (BPN), points to the construction of Nusantara International Airport in Penajam Paser Utara, East kalimantan, Indonesia, June 11, 2024. [Land Bank Agency]

The ambitious project to build Indonesia’s new capital city, Nusantara, is facing mounting criticism over its land acquisition practices. While officials maintain thier commitment to fair dealings, accusations of land grabbing and inadequate compensation are fueling protests and raising serious ethical questions.

Parman Nataatmadja, head of the National Land Agency, insists the agency is working to resolve agrarian conflicts. In a statement,he declared, “We are here to provide a solution for resolving agrarian conflicts. For investors, we guarantee that the land is clean and clear, while respecting community rights.” He acknowledged challenges, stating, “Ther are gaps in understanding between the agency and local communities, requiring constant interaction to align perceptions.”

However, these assurances are not convincing all stakeholders. Husen suwarno,an activist with the East Kalimantan Coastal Working Group,alleges the land acquisition process is essentially state-sanctioned land grabbing. “In practice, they are seizing land in the name of the state through the Land Bank Agency,” he asserts.

Protests Erupt Over Low Compensation

In late November,the simmering discontent boiled over. Dozens of Pemaluan villagers,whose land was taken for two new toll road sections near Nusantara’s administrative centre,rallied to protest what they deemed woefully inadequate compensation. the government’s offer ranged from 145,000 rupiah to 218,000 rupiah ($9.30 to $14) per square meter. This prompted Abdul Kahar, the local neighborhood association head, to declare, “We don’t agree with the offered price.” Villagers argued the compensation didn’t reflect the land’s true value or its agricultural potential.

Related Stories

- Indonesian president will finish out his final term working from future capital

- Indonesia’s Nusantara to host I-Day events despite drinking water, construction delays

- Indonesia’s new capital project stirs controversy again with backlash over demolition notices

- Indonesia celebrates Independence Day in future capital city

nusantara’s Shadow: Land disputes Cast a Pall on New Capital Project

The construction of Nusantara,Indonesia’s new capital city,is progressing,but a shadow looms large over the ambitious project: widespread land disputes. While president Joko Widodo’s July 28, 2024, inspection of the new toll road connecting Nusantara to Balikpapan showcased infrastructure development, the human cost of relocation remains a pressing concern.

One farmer, Kamarudin, paints a picture of displacement and uncertainty. “They said it would be paid in stages,” he recounts, his voice laced with frustration, “But there has been no news about it.” Kamarudin’s plight is echoed by others who feel pressured into accepting inadequate compensation for their land and livelihoods. He fears that even if compensation arrives, the soaring cost of living will swallow it whole, leaving him unable to invest in new farmland and rebuild his life.

The issue extends beyond individual cases. kahar, another affected resident, describes the coercive tactics used to secure land: “When they mention court proceedings, people just comply,” he explains, highlighting the intimidatory pressure faced by those resisting relocation. This underscores the lack of equitable negotiation and the daunting legal battles faced by many landholders.

While the head of the land agency,Parman,asserts that monitoring systems are in place to prevent land misuse and overlapping claims,stating,”If conflicts arise,we resolve them through persuasive methods,” the reality on the ground tells a different story. Disputes persist, raising serious questions about the effectiveness of these measures.

Trubus Rahadiansyah, a public policy analyst at Trisakti University, criticizes the government’s approach. He argues for a fairer system, advocating for self-reliant valuations to ensure market-value compensation. “This is essentially a sale and purchase process,” he stresses. “There must be negotiations, not confiscations.” His call for clarity and fair compensation resonates with the concerns of those displaced by the new capital project.

## Nusantara’s Shadow: A Dialog on Land disputes

**Avery Parker:** The Nusantara project, while ambitious, is facing important backlash due to its land acquisition practices. The article highlights instances where compensation offered to displaced communities, like Kamarudin’s, is far below market value, leading to accusations of land grabbing. Kamarudin, a farmer with a decades-old land certificate, received only $63,000 for his seven-acre plantation, despite earning a steady $260 a month from it. This raises serious questions about the fairness and transparency of the process. What are your thoughts on the government’s approach?

**Jordan Reed:** The government insists they’re committed to fair compensation and resolving conflicts,citing the efforts of the National Land Agency. Parman Nataatmadja, the head of the agency, emphasizes their work in clearing land titles and ensuring investor confidence while supposedly respecting community rights. Though, the reality on the ground, as illustrated by cases like Kamarudin’s and the Pemaluan villagers’ protest over ridiculously low compensation ($9.30-$14 per square meter!), paints a drastically different picture. The discrepancy between official pronouncements and the lived experiences of affected communities is striking. The government’s claim of resolving conflicts through “persuasive methods” rings hollow when faced with widespread discontent and protests. The assertion that the process is a “sale and purchase” as suggested by Trubus Rahadiansyah is crucial here; without genuine negotiation and fair market-value compensation, this is simply a forceful seizure of property. The low compensation offered to Pemaluan villagers, who lost land for new toll roads, further underscores this issue.

**Avery Parker:** The article mentions the use of eminent domain, which allows the government to acquire land for public works even without consent. But the key is “provided fair compensation is given.” Clearly,that condition isn’t being met.The scale of the project – 260,000 hectares – exacerbates thes challenges.How can the government reconcile the ambition of Nusantara with the fundamental rights and livelihoods of its citizens? Is the current system adequately equipped to handle the complexities of such a large-scale undertaking?

**Jordan Reed:** The fundamental problem lies in a lack of transparency and a failure to prioritize genuinely equitable valuations. It seems the current system prioritizes the project’s rapid advancement over the well-being of local communities. The government needs to implement stricter regulations and self-reliant oversight mechanisms to ensure fair compensation is steadfast via obvious means, involving community participation in the valuation process. Instead of relying on the current land bank agency, possibly biased toward the project, self-reliant valuation methods led by independent assessors could prevent future injustices. The government also needs to actively engage with affected communities in meaningful negotiation, rather than using coercive methods that appear to prioritize the state’s needs over individual ones. Only through genuine dialogue and equitable compensation can the trust of the local populations be restored and the project’s sustainability be secured in the long run.Ignoring this is not only ethically wrong, but it’s also a recipe for continued social unrest and potential project delays.