2024-02-02 13:16:15

Few objects have gone through the history of African music like plastic sandals. Named “lêkê” in Ivory Coast, in the 2010s they became the emblem of “People’s China”, a name given to themselves by fans of DJ Arafat, because they were, in the words of the late artist: “ as numerous as the Chinese. Already in the early 1990s, they were the shoes for student marches and the early days of zouglou. Today, rap stars have reappropriated them, and the Gucci brand has offered its own variation. A look back at a story in music and images of the most famous sandals on the African continent.

From Auvergne to Eritrea, an African history

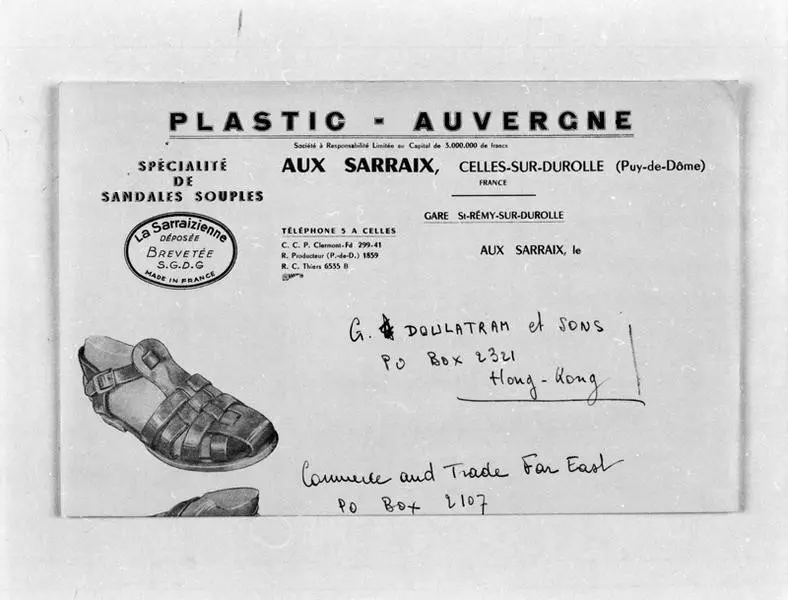

The story begins in a village whose name probably means nothing to readers: the place called “Les Sarraix” in Puy-de-Dôme in Auvergne, a rural and mountainous region in central France. It was there that in 1946, Jean Dauphant, a professional cutler, had to face a dilemma. He had just ordered several pallets of a new product that a salesman had sold him to wrap the handles of his knives, a supposedly revolutionary plastic which ultimately turned out to be completely unsuitable for this task: PVC. Not wanting to lose his investment, Jean Dauphant had the idea of using this soft plastic to replace the leather of the sandals. First called “sarraizienne” then “plastic – auvergne”, plastic sandals were born, but the product only met with very limited success at that time.

Florian Vallée, who investigated these sandals for three years to make his film “The Odyssey of the Plastic Sandal: the extraordinary destiny of an ordinary object”, explains that it was through the intermediary of a French trader based in Dakar, also from Auvergne, that these sandals will be exported to Africa, convinced that they can be successful there. But, contrary to his hopes, the settlers were not interested in these shoes, preferring leather models. On the other hand, the local “haves” appropriate them because they find them practical and adapted to the climate. In the 1950s, these were the shoes of the local elites in Senegal.

At the end of the decade, the manufacturer Bata, already established on the continent and feeling the wind of independence blowing – and a new market opening up – decided to reproduce these shoes to distribute them on a larger scale to Africans. In 1957, their promotion was done through music, with a piece to glorify this piece of plastic, recorded by the “grandmaster” of Congolese rumba who became the brand’s ambassador: Franco Luambo of OK Jazz.

Throughout Africa, the Bata model became the shoe of the lower middle class, propelled by this promotion of one of the biggest stars of the time. But at the end of the 1970s, the elites abandoned it for more bourgeois shoes and Bata stopped producing them, the factories no longer being able to compete with local producers. This marks the end of the brand’s empire on the continent.

Local production, however, continues to develop, but the sandal loses its aura and becomes the shoe of the poor, except in Eritrea, where, during the 80s, it is the shoe of combatants who make it with recycled tires on a unit clandestine production. The shoe is so popular among them that they are buried with it when they die in battle. After gaining independence from Ethiopia, sandals became an Eritrean national emblem, praised in poems, frescoes and monuments.

At the same time as these plastic sandals beat the mountains at the feet of the fighters, it is at the other end of Africa, in Ivory Coast, that their musical history will be forged.

In Ivory Coast: lêkês, marches and “People’s China”

If, in the 1980s, Monique Seka stood out on stage by wearing a model of plastic sandals with heels, still known today as “sekamania” in Ivory Coast, it was especially from the early 1990s that the lêkê will become a musical emblem of a new genre: zouglou. For Pat Sako, the leader of the Espoir 2000 group:

The lêkê first of all is a shoe which, at the time of the 1980s, was initially the least expensive. It was made of rubber, you might get it cheaply. And in 90 when zouglou arrived we made it a fashion, we even saw Uncle Bouba [célèbre animateur ivoirien] which had concepts of lêkê and everything, so they associated this shoe with zouglou. This is how lêkê came to zouglou, and how people later adopted it.

As explained by Didier Bilé, considered among the students at the origin of zouglou as the “Z1”, the first artist of the genre, the movement very quickly became popular in the slums of Abidjan from Yopougon to Anoumabo, from where The most famous artists of their generations will emerge: Les Salopards, Yodé & Siro, Espoir 2000 and Magic System. These young people then wore lêkê for economic reasons, but will transform these sandals into a fashion object by showing off with them. Even today, while he has become an international star, A’Salfo, the leader of Magic System, proudly assumes this heritage.

In the 2000s, the lêkê will also become politicized in Ivory Coast because they become the shoes of the great patriotic marches, this movement of young people who supported the current president Laurent Gbagbo in the face of the armed rebellion. We notably see the lêkê on the feet of the leader of the movement, Charles Blé Goudé, a great fan of zouglou from whom he borrowed the style. During his trial at the International Criminal Court, during which he was acquitted, he went to his hearing in… lêkê.

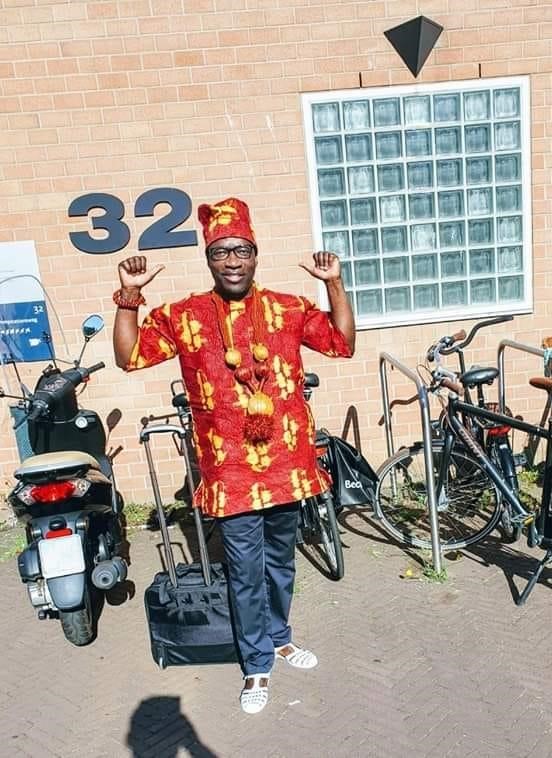

Throughout the 2000s, the Zouglou movement lost steam for a while with the immense success of the coupé-décalé, whose first stars preferred to ostensibly display JM Weston or Italian luxury shoes on their feet. But that was without taking into account the rise of the “Zeus of Africa”, one of the biggest stars in Ivory Coast and French-speaking Africa for almost a decade: DJ Arafat. The latter, who ardently frequents Princess Street and its DJ booths, sometimes sleeping on the floor, wore these shoes as an emblem. “People’s China”, its many fans, have reappropriated them and wear them for all occasions. As one of them, met at the Adjamé market with his lêkê worn over sports socks, tells us:

It’s in chokoya mode. What we call chokoya means you dress well, you wear socks. Instead of putting pancakes there [chaussure sebago], you put on white socks and white lêkê. With tight jeans, it’s just the chain that’s missing to make Arafat.

Faced with this craze for lêkê, manufacturers have not remained passive and have developed new ranges which differ in slight details such as the position of the buckles or the tangle of the straps, but they maintain a very low price, less of 1000 Fcfa (1€50) per pair. They give the lêkê the names of personalities: Boli, Drogba, Messi. Counterfeits also feature the logos of major streetwear brands, and the shoes come in multiple colors. Lêkê are worn as much for going to work, playing football and maracana as for going out flirting or relaxing, each pair has its own purpose.

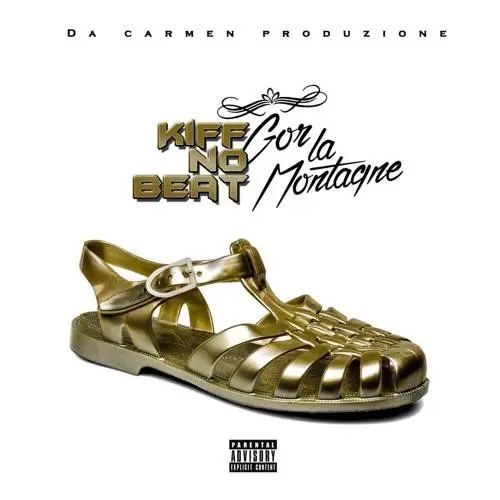

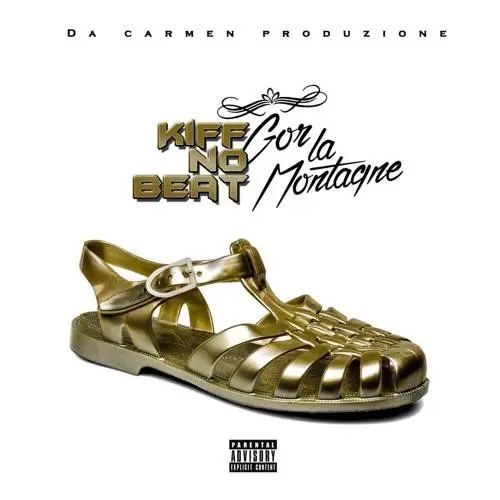

Today, fashion hasn’t slowed down and it’s rappers who are reclaiming these shoes. Kiff No Beat, who almost single-handedly launched the ivory rap fashion in the early 2010s, notably chose golden lêkê to illustrate one of their single, “Gor La Montagne”, in homage to one pioneers of the Ziguehi movement (the “big arms” of the 1990s).

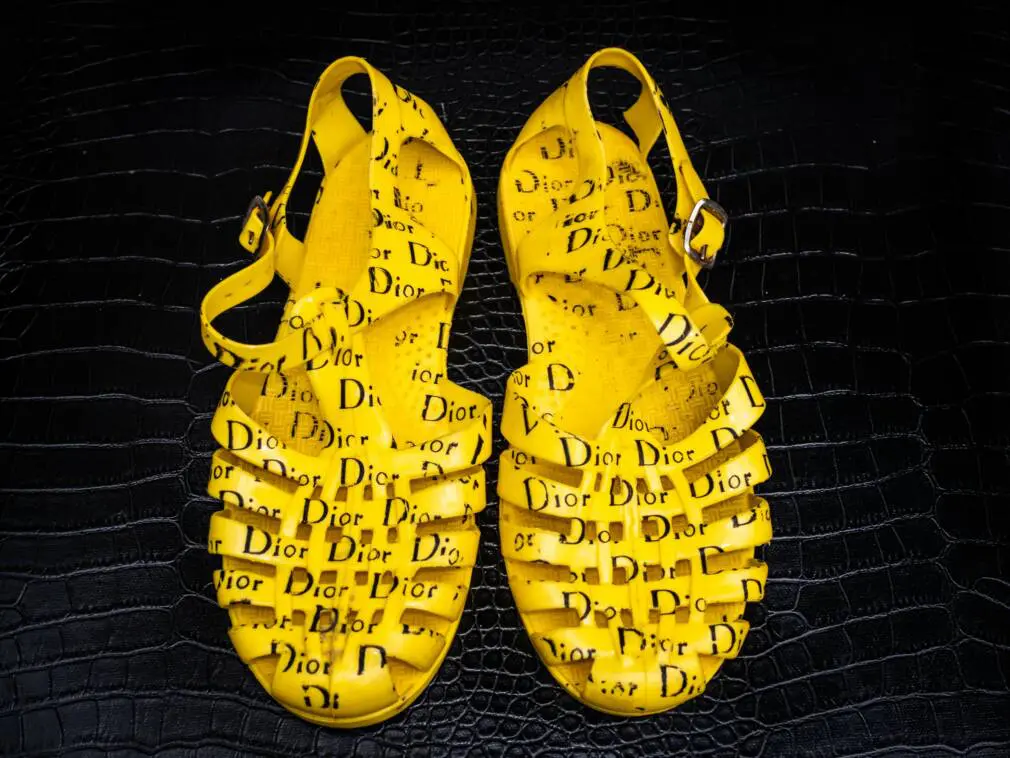

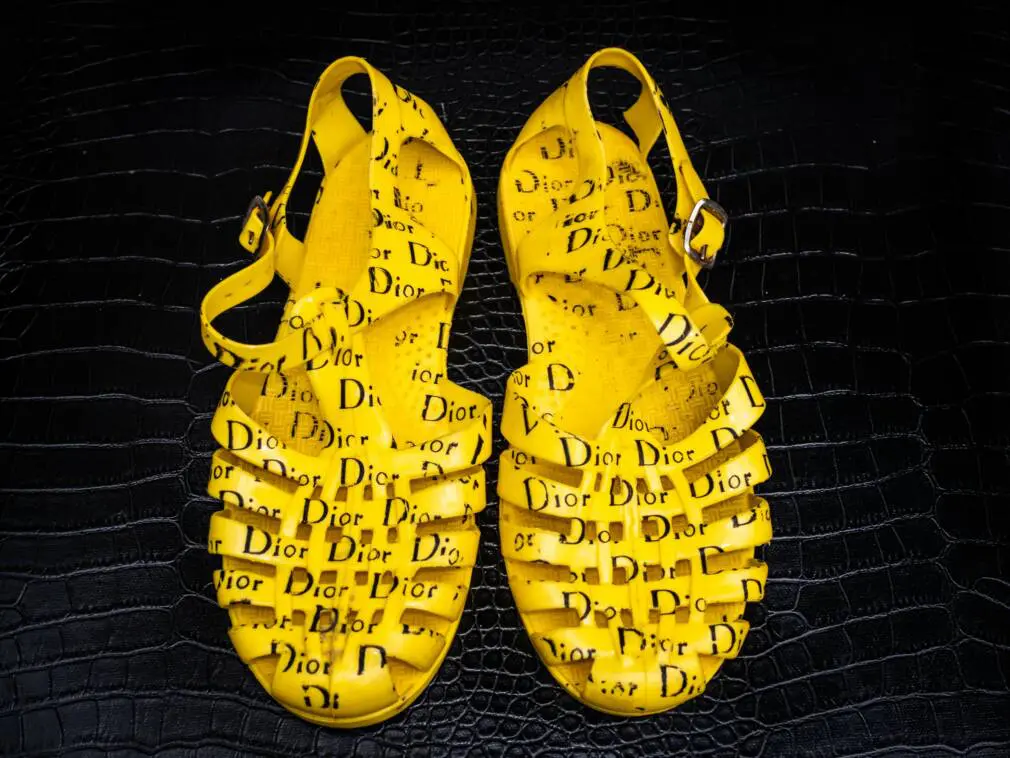

Mosty, one of the new sensations of ivory rap, dedicated his first “freestyle”, in 2020, to these shoes. As for personalities, we can no longer count those who appear in lêkê, from the Ivorian international footballer Didier Drogba to the Congolese rumba star Fally Ipupa, perhaps in homage to his illustrious ancestor Franco Luambo? In any case, Fally Ipupa does not wear the Bata model promoted by his illustrious predecessor, he preferred a somewhat more luxurious variation, lêkê produced by… Gucci, price: €450 (300,000 Fcfa).

1708171736

#Lêkê #music #sandals