- Mariana Alvim

- BBC Brazil correspondent, Sao Paulo

August 12, 2022

image source,Getty Images

Research suggests that shrew may be an animal host for the virus.

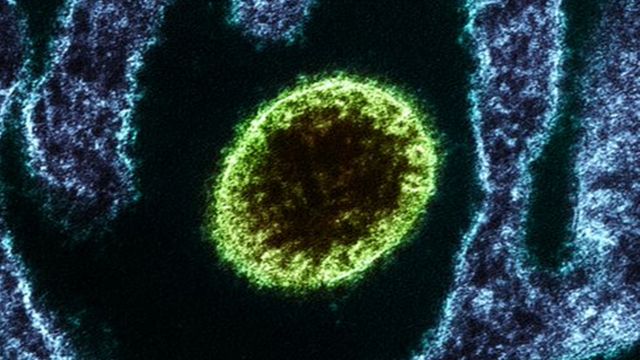

An international team of scientists has announced the discovery of a new virus of the Henipavirus family, which is known to cause outbreaks of highly lethal infections in humans.

The research team said that between 2018 and 2021, the “Langya henipavirus” (LayV, commonly known as “Langya virus”) infected at least 35 people in China.

In a letter published Aug. 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine, the scientists wrote that there is no indication that the “Langya virus” can be transmitted through human-to-human contact. They also suggested that the source of infection may have come from an animal — the team found evidence that shrews may be the natural reservoir for the virus, but further research is needed to confirm this.

Of the 35 cases identified in China, 26 have been carefully studied. The study revealed that all patients had a fever, and some cases were accompanied by symptoms such as tiredness (54%), cough (50%), headache (35%) and vomiting (35%). Scientists also found some abnormalities in liver function (35% of patients) and kidney function (8%). But there is no information on any fatalities yet.

Experts interviewed by the BBC say the discovery of a new virus does not necessarily mean a new pandemic will occur. But the discovery of a new virus in the Henipaviridae family is worrying because other pathogens in this family have previously caused outbreaks and severe infections in Asia and Oceania.

“No hot spots”

These outbreaks are caused by the “cousins” of the “Langya virus”, Hendra virus (Hendra henipavirus, referred to as HeV) and Nipah virus (referred to as Nipah virus, referred to as NiV). Hendra virus is rare, but has a 57 percent fatality rate, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

In the case of Nipah virus, it had a fatality rate of 40-70% of outbreaks reported from 1998 to 2018. Both viruses can cause respiratory and nervous system problems.

India suffered one of the worst known outbreaks of Nipah virus in 2018, with 17 deaths from 19 confirmed cases in the Indian state of Kerala.

image source,Getty Images

China finds cases of infection among some patients who come to hospital with fever (file photo)

Comparing this data with Covid-19 mortality is difficult due to the use of different methods and differences in data provided by different countries and over time. However, it can be said that the lethality of Hendra virus and Nipah virus at the time of the outbreak was significantly higher than that of the new crown epidemic that first broke out in China in December 2019.

Jansen de Araujo, a professor at the Emerging Virus Research Laboratory at the University of São Paulo, believes that the discovery of “Langya virus” does not mean the beginning of a new pandemic, because the researchers who discovered the new virus have been monitoring it for a long time. .

“What’s being observed is not a hotspot (where there is an increase in disease prevalence) like Covid-19,” said Prof. Araujo. It differs from the virus that causes Covid-19, which spreads very rapidly around the world.

Ian Jones, a professor of virology at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, pointed out that so far the “Langya virus” has not shown the ability to transmit effectively from person to person.

“No obvious sign of mutation”

“More importantly, neither Hendra nor Nipah is showing signs of a pandemic,” Professor Jones told the BBC.

“There is no clear sign that they are mutating to be more transmissible, and there is some suspicion that this will also be the case with the ‘Langya virus’,” added Professor Jones.

Still, both experts see the need to continue monitoring new cases.

image source,Getty Images

Nipah virus is the “cousin” of New Langya virus.

The team that discovered the “Langya virus” reported that all infected patients were residents of Shandong and Henan. There was no close contact between these patients and no history of passing through the same places. The researchers traced contacts between the nine patients and their relatives and found no cases of infection that might prove human-to-human transmission.

More than half of those infected were farmers, which is relevant given that the virus was contracted through some form of contact with animals.

When trying to look for genetic traces of “Langya virus” in domestic and small wild animals, scientists found that shrews had the highest detection rates for the virus — more than 25 percent of shrew assays found them to carry traces of the virus. The team thinks shrews may be the virus’ “natural hosts” — animals that are infected with the pathogen, but don’t get sick themselves, unlike their ultimate hosts, such as humans.

bat host

Langya’s “cousins” Hendra virus and Nipah virus are known to use bats as their natural hosts. There are no known human cases of Hendra virus transmission, but people can become infected through contact with the bodily fluids, soft tissues or feces of infected horses, the CDC said.

On the other hand, Nipah virus is known to be contracted through contact with infected animals, such as bats and their bodily fluids, or through close contact with infected people, the CDC said.

Dr. Michele Lunardi, an animal virologist at the State University of Londrina in Brazil, and colleagues published a 2021 review of research on heniba virus. The authors note that there are currently no known treatments for human infection with Hendra and Nipah viruses, and they conclude that Nipah virus has “the capacity to cause a devastating pandemic.”

image source,Getty Images

Fruit bats are known hosts of Henibaviridae viruses

However, Professor Jones sees no reason to panic.

He explained, “In my opinion, Nipah does not have a high risk of causing a pandemic. The risks posed by the virus to humans are understandable, but they can still be prevented through education rather than, say, the development of a vaccine.”

Professor Jones also pointed out that what we currently know regarding Nipah virus is that it replicates better in the human nervous system, which makes it less transmissible from person to person than the new coronavirus that replicates the virus in the respiratory tract.

“It’s important not to panic when a new virus is discovered,” he said. “Scientists are always looking for new viruses, especially following Covid-19.”

“The world has many terrible viruses, but that doesn’t mean we’re going to be exposed to them,” he said.

Note: Additional reporting by Fernando Duarte for this article