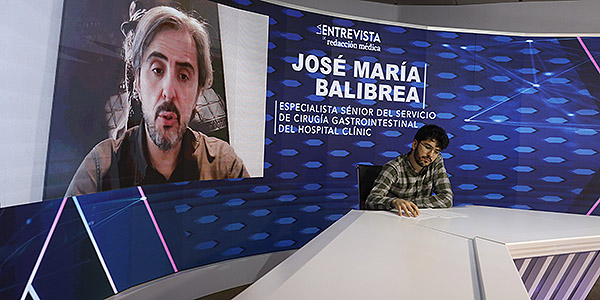

José María Bailbrea, senior specialist in Gastrointestinal Surgery at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Near 11,000 patients are in the queue to be able to access a bariatric surgery in Spain, one of the surgical procedures aimed at weight loss. The Covid-19 pandemic has accentuated the delay, which has already lasted on average up to 400 days, according to figures from the Spanish Society of Obesity Surgery (DRIED).

On Medical Writingwe reflected on this reality with Dr. Jose Maria Balibrea, senior service specialist Gastrointestinal surgery of the Hospital Clínic and full professor at the University of Barcelona. His testimony makes it possible to clarify the consequences of postponing this operation for patients with morbid obesity, its impact on public coffers or when it is advisable to perform it in adolescent patients.

|

Complete interview with José María Balibrea, senior specialist of the Gastrointestinal Surgery service of Hospital Clínic. |

What is the current waiting list to access bariatric surgery in Spain?

More than the waiting list, I would say that less than 1 percent of the patients who might benefit from this resource, which is still a part of the global treatment that is the operation itself, have access. So it depends. There are important differences between communities but the standard mean, let’s say, might be between 9 and 11 months. There are communities that may go faster and even within the autonomies there are differences but it is difficult for a patient to have surgery quickly, so to speak.

How has Covid-19 changed this reality? Have the waiting lists been lengthened?

Obviously, during the pandemic what we have had to do has been to prioritize other types of surgeries and in fact from the Spanish Association of Surgeons our working group tried to make it more or less clear what the priorities were. Emergencies, cancer surgery, oncological surgery, when resources were not available for everyone, were the priority. Benign surgery, such as obesity surgery, suffered a lot. So, these lists have increased, but I think that the fundamental effect is not so much that they have increased, but that during this time the patient with obesity worsens because he gains weight in most cases. And there are already publications regarding this. Our group and several Spanish and international groups have confirmed this. And, on the other hand, because the diseases associated with obesity also worsen.

What is the main handicap that prevents these waiting lists from being reduced? Bearing in mind that the availability of personnel, operating theaters and also public investment play a role here…

|

José María Bailbrea explains the impact of the pandemic on bariatric surgery |

Bearing in mind that the process of treating obesity is not a solely exclusive treatment, so to speak, independent of the surgical intervention, we have the part of the operating rooms. Obviously, these are surgeries that cannot be done in any facility and that in order to have optimal results, like the ones we have today, the practice of all groups that dedicate ourselves to this need appropriate facilities, with a trained team: surgery, anesthesiology, operating room nursing… The same thing happens, with adequate operating rooms. They are not usually patients who need intensive care but a few hours of observation, etc.

In addition, what is needed is the rest of the team and this is closely linked to other things that the pandemic has revealed, since we work in multidisciplinary teams where the role of endocrinology is absolutely key. The role of dietitians and nutritionists as well. Of course, the role of the psychology and psychiatry team, but also Primary Care since they are often the first to detect the disease and refer us to specialized units.

Not only do we need more operating rooms, more trained personnel or more material, we need more infrastructure to be able to guarantee that the multidisciplinary units can attend correctly and not only the pre and intra, but also the postoperative and adequate follow-up for all these patients. During the pandemic, for example, the issue of mental health is closely related. We also need mental health for our patients and Primary Care the same. The collapse of Primary Care means that these patients arrive less and later at our units.

|

José María Bailbrea, senior specialist in Gastrointestinal Surgery at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

Before you told me that you can gain weight as a result of this delay in waiting lists, what other consequences does it have for a patient that the time is prolonged until they can access an intervention?

We have easily assessable consequences, such as a patient who has accompanying diseases or comorbidities as it was called before, such as type 2 diabetes, which is very frequent. Perhaps their control is worse and that can affect in the medium and long term the evolution of the complications associated with that diabetes itself, hypertension, dyslipidemia… but also the work that the rest of the teammates do , which is extremely complicated as it is to prepare the patient emotionally, psychologically, educationally. That is, the patient has to learn new habits. If that stops suddenly, the patient goes backwards and then we would have obvious consequences for his health.

There are times when we have patients who urgently need the operation, patients who are even awaiting a kidney or liver transplant. But those who may not need this procedure so urgently do a very thorough preparation and are ready for a change in their lifestyle. If this stops suddenly, obviously, it costs a lot to recover it.

José María Bailbrea, senior specialist in Gastrointestinal Surgery at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

Containing the waiting lists would imply an economic effort on the part of the Administration. What impact do you think this might have on the National Health System? Could it become efficient?

The issue of the cost-benefit balance of the efficiency of bariatric surgery for years has been quite clear that it is very positive. In fact, I remember a post on The Economics, which I think is from three or four years ago, in which obviously the patient with obesity is a patient who consumes many resources, not only pharmacological, which is the most obvious, but visits to the hospital. And let’s not forget the indirect costs, that is, what the patient stops doing: sick leave, inability to integrate into a community, into a society. And, of course, the intangible costs that are the suffering, the isolation, the discrimination that these patients may suffer.

So, from that point of view of the coldest, that is, cost-benefit, the strategy is favorable. It is clear that if an overeffort were made or basically a reorganization of resources taking into account epidemiology and more funds were allocated, more resources to promote the treatment of obesity, deep down we would be benefiting many patients. In addition, that would generate a much more favorable cost-benefit balance. We are talking regarding the fact that around 6 or 7 percent of the global population might be a candidate. I understand that there are other pandemics, I understand that there are other diseases whose prognosis in the medium or short term is worse, but obesity, as recognized by the WHO, is one of the great problems we have and obviously a better investment or a reconsideration or redistribution of funds would surely be favorable cost-benefit.

How many interventions should be done to get closer to an average that would be ideal?

That is quite a difficult question because it is striking that perhaps a neighboring country, such as Portugal, has a strategy in which proportionally, of course, the number of surgeries is greater. We should probably be doing, and I don’t want to be too alarmist, twice as many interventions as we are doing now. In figures from the Spanish Society of Obesity Surgery, in the Obesity section of the Spanish Society of Surgeons, the Spanish Association of Surgeons, we should probably be doing around 8,500 surgeries a year. It would be appropriate in our context.

José María Bailbrea, senior specialist in Gastrointestinal Surgery at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

To understand a little better how this type of intervention works, when is it advisable to do it in pediatric patients and what impact does it have on containing obesity?

Actually, the experience in pediatric patients is very limited. However, in adolescents it is a strategy that has been implemented and, in fact, in groups like Vall d’Hebron, which was the institution where I used to work, they did have a comprehensive program and what was achieved was to intervene adolescents because the child is of developmental age. It is an issue that is quite controversial on which there is no conclusive scientific evidence. However, in adolescents – we are talking regarding patients from 16 or 17 years old -, in the United States, where this problem is also pressing, it has been recommended. I insist, in the context of multidisciplinary programs. Carrying out this type of intervention has been seen to have good results in the medium and long term and this has been published in prestigious journals such as the New England Journal Of Medicine. So it might be an option but in the case of children especially I don’t think surgery should be the first option at all.

Taking into account this quite complete x-ray that we have done, what message would you send to the Ministry of Health or to those responsible for the Ministries of the autonomous communities?

In this I believe that it is necessary to be clear and fortunately I believe that we have good representatives in the technical positions of this type of institutions. In fact, I work in Catalonia and the truth is that a truly commendable effort is being made to reorganize resources and how obesity is treated. But I think that globally what needs to be done is to look at the epidemiology of the society in which we live and how resources should be distributed.

I believe that today, and I speak of my specialty, there are problems that are fortunately being solved without surgical treatment, such as liver transplants. It is a procedure that is going to decline basically because we already have an effective treatment for the C virus and, however, oncological pathology, obesity or abdominal wall pathology are going to continue to grow due to the progressive aging of society and because many habits have not changed. So I think my message would be: let’s look at epidemiology in the face of attribution and redistribution of resources, not only in what doctors receive to work, but even in how we train doctors, especially surgeons.

Although it may contain statements, data or notes from health institutions or professionals, the information contained in Medical Writing is edited and prepared by journalists. We recommend the reader that any questions related to health be consulted with a health professional.