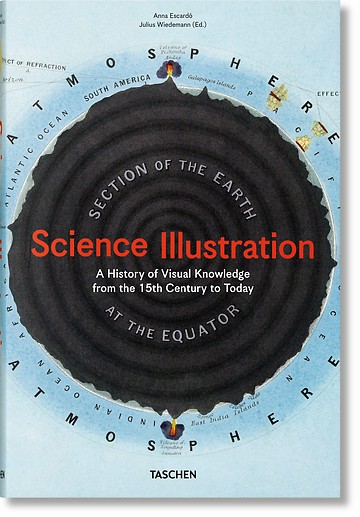

Scientific knowledge begins with an idea. This is usually only as good as its communication succeeds. With her compendium “Science Illustration”, Escardo makes it clear that this principle has been in place for around 500 years, in which she collects around 250 illustrations and tells the history of science from the early modern period to the present day as media history.

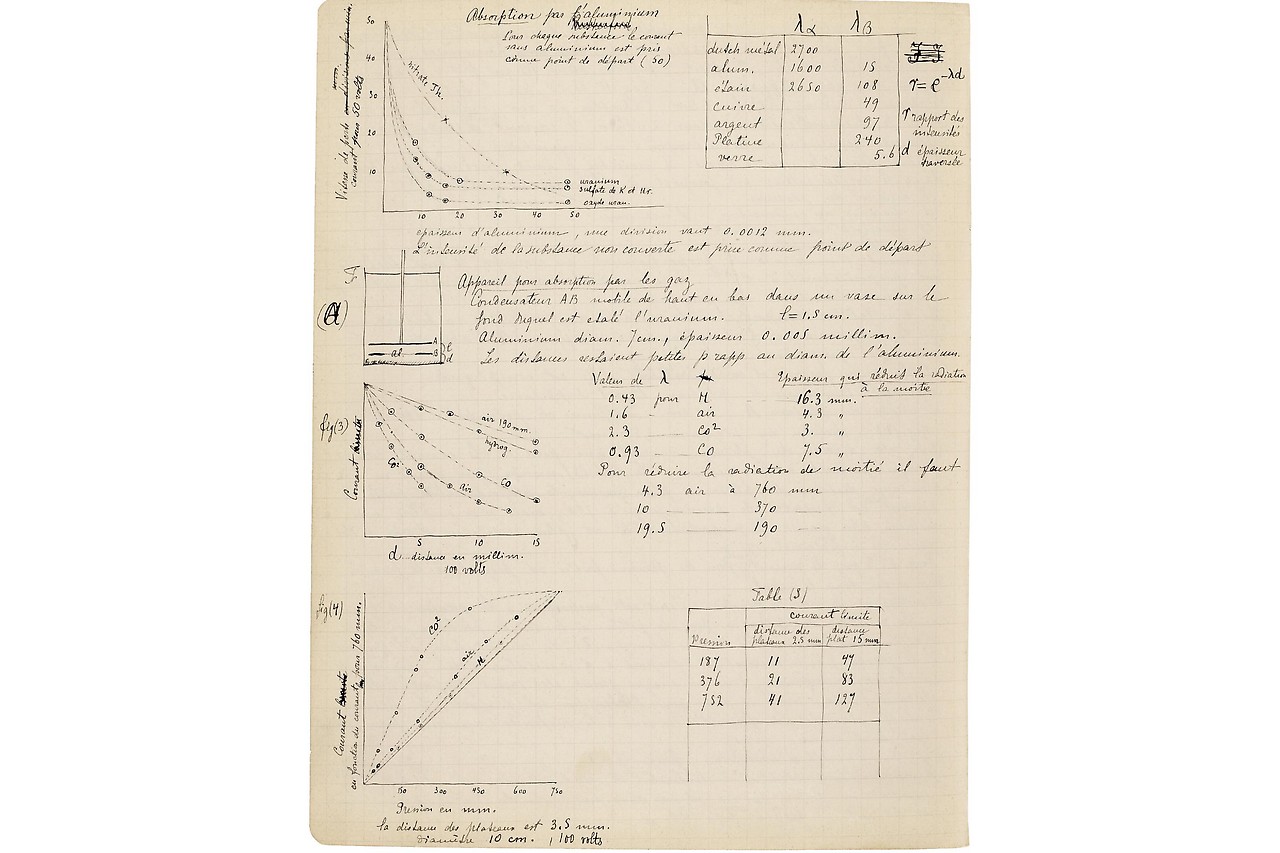

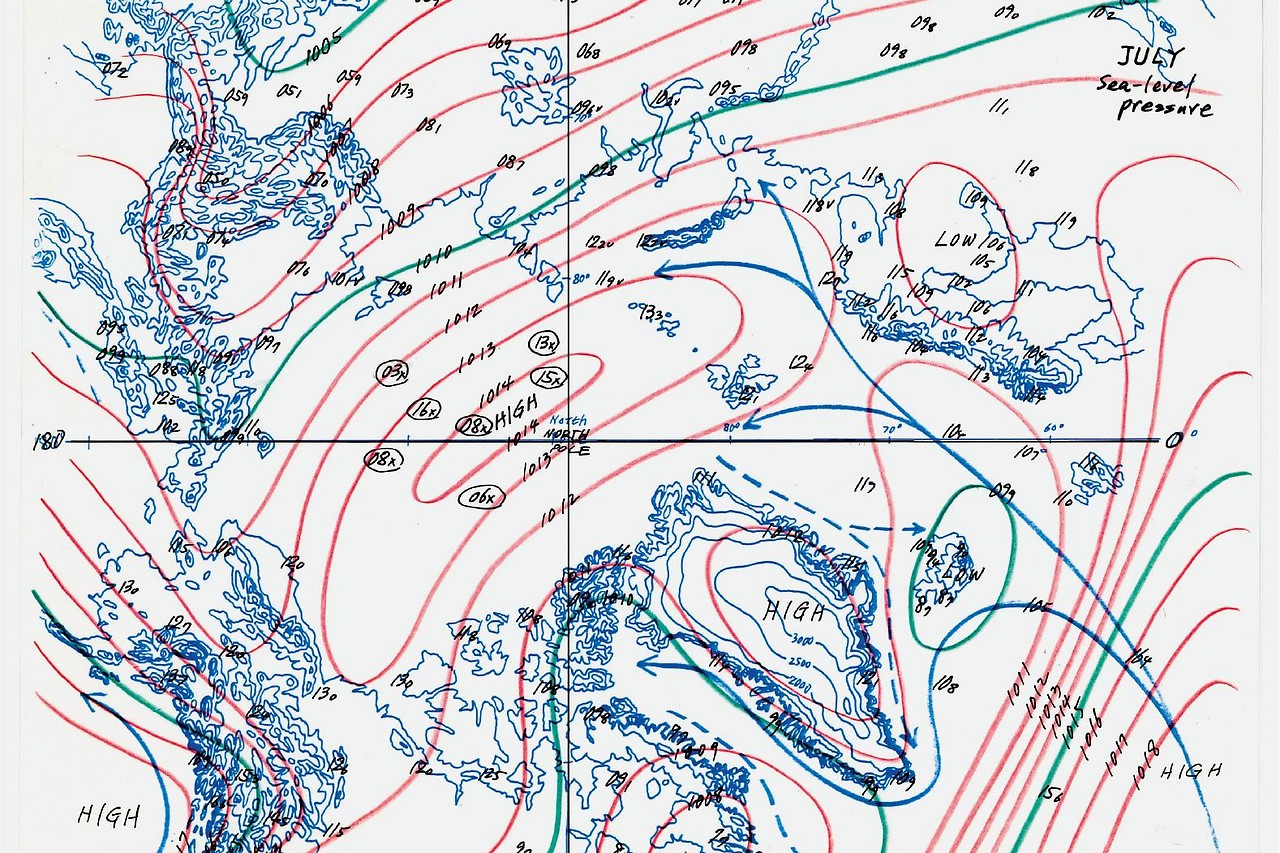

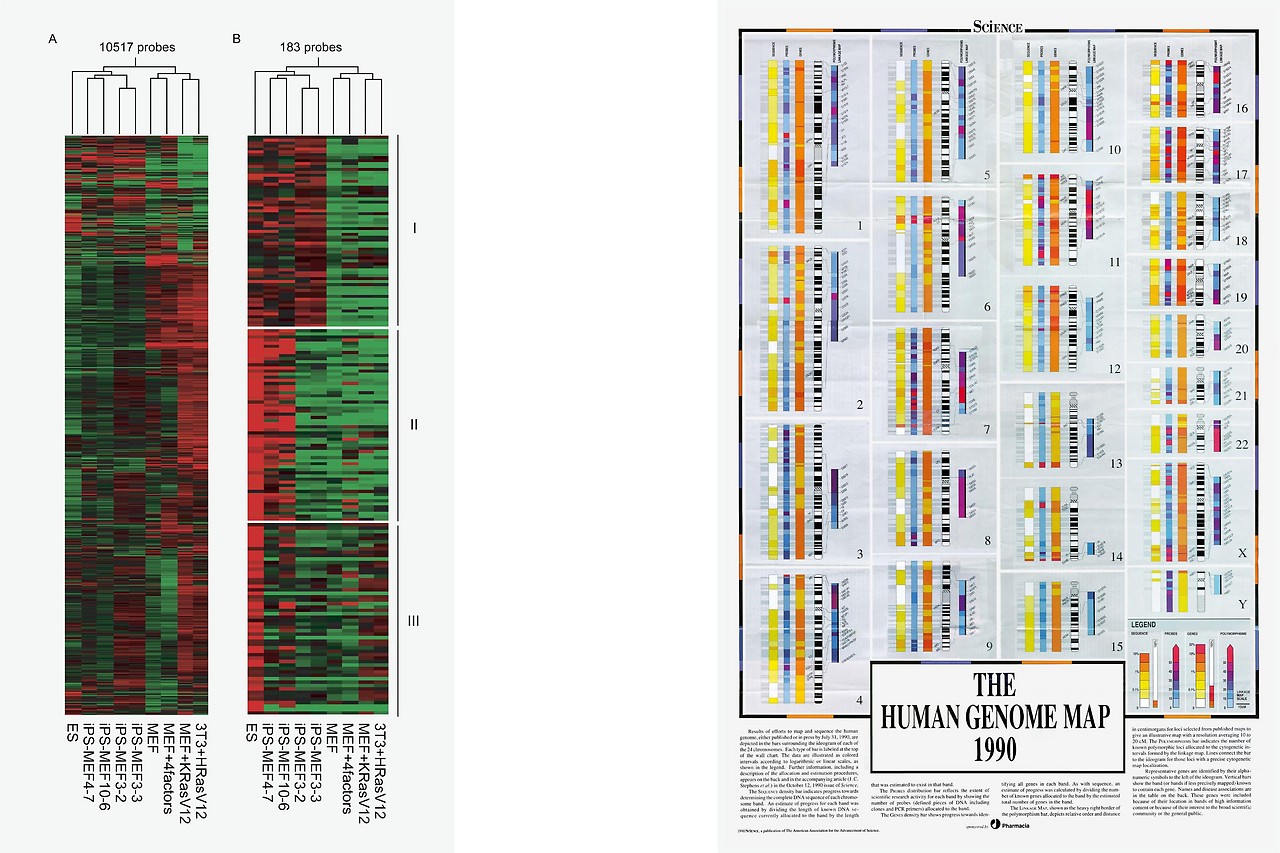

From an early nautical map of the Gulf Stream to the coronavirus, discoveries are often better captured by images than words. The pictures, some of which have become iconic, always went in step with technical upheavals. Innovations such as photography have never completely abolished earlier techniques – such as sketches – through history: “With an illustration, you can give a chronological sequence or complex data a visual form, a photo only shows a single moment,” Escardo explains to ORF .at. A ubiquitous example are maps with temperature profiles and climate diagrams.

Photo series with 8 pictures

Between art and science

Escardo locates the first scientific illustrations in the modern sense in handwritten medieval books that were written in monasteries and, like the “Tractatus de Herbis” created in Italy in 1440, wanted to convey systematic knowledge, there in botany, through comparative illustrations.

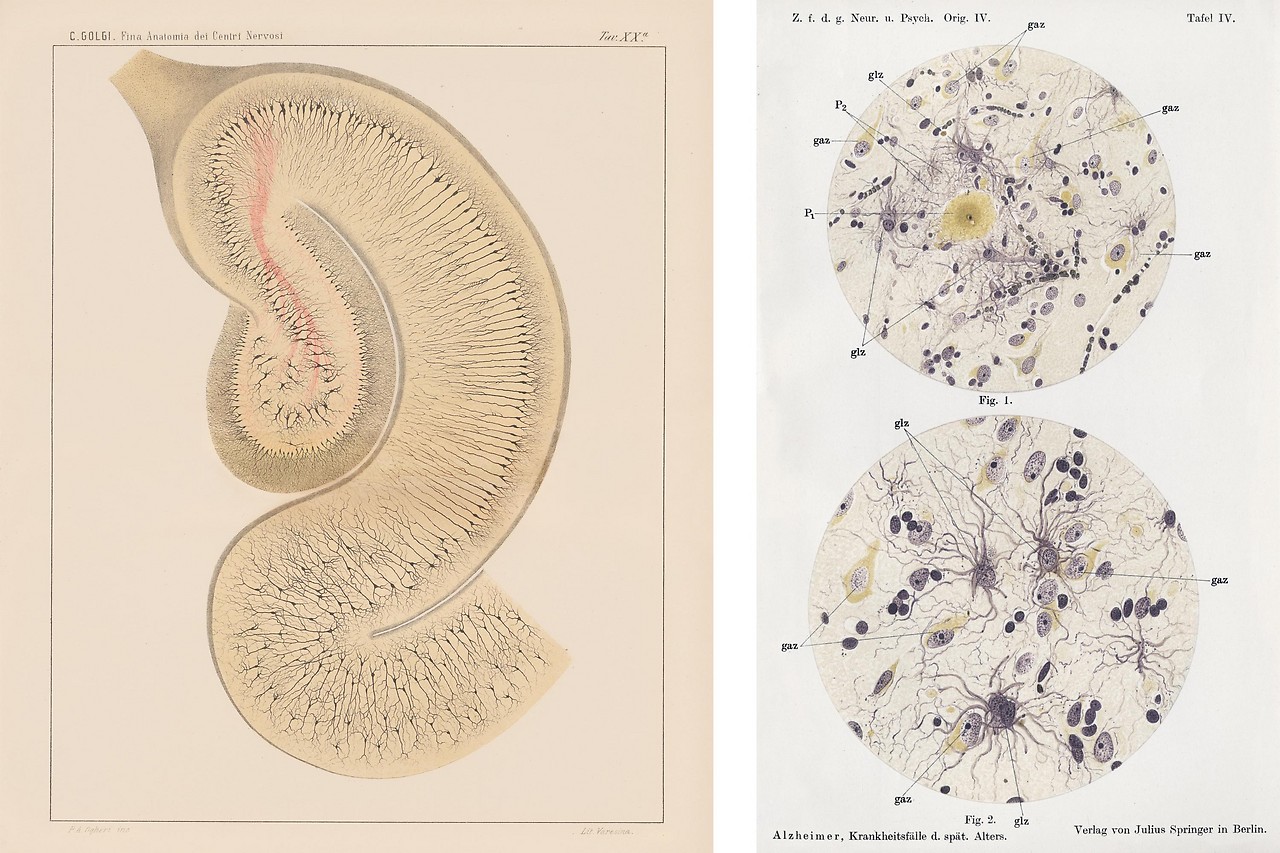

For her, however, the era of a visual history of science only began with the media revolution of the invention of the printing press. Andreas Vesalius’ “De humanis corporis fabrica” (1543), the first anatomy atlas in which corpses served as illustrative material for the studies, also dates from the early phase of this epoch. The artistic execution of the illustrations is attributed to the old master Titian. Here begins a fascination for the human body that extends to the visual arts of the present.

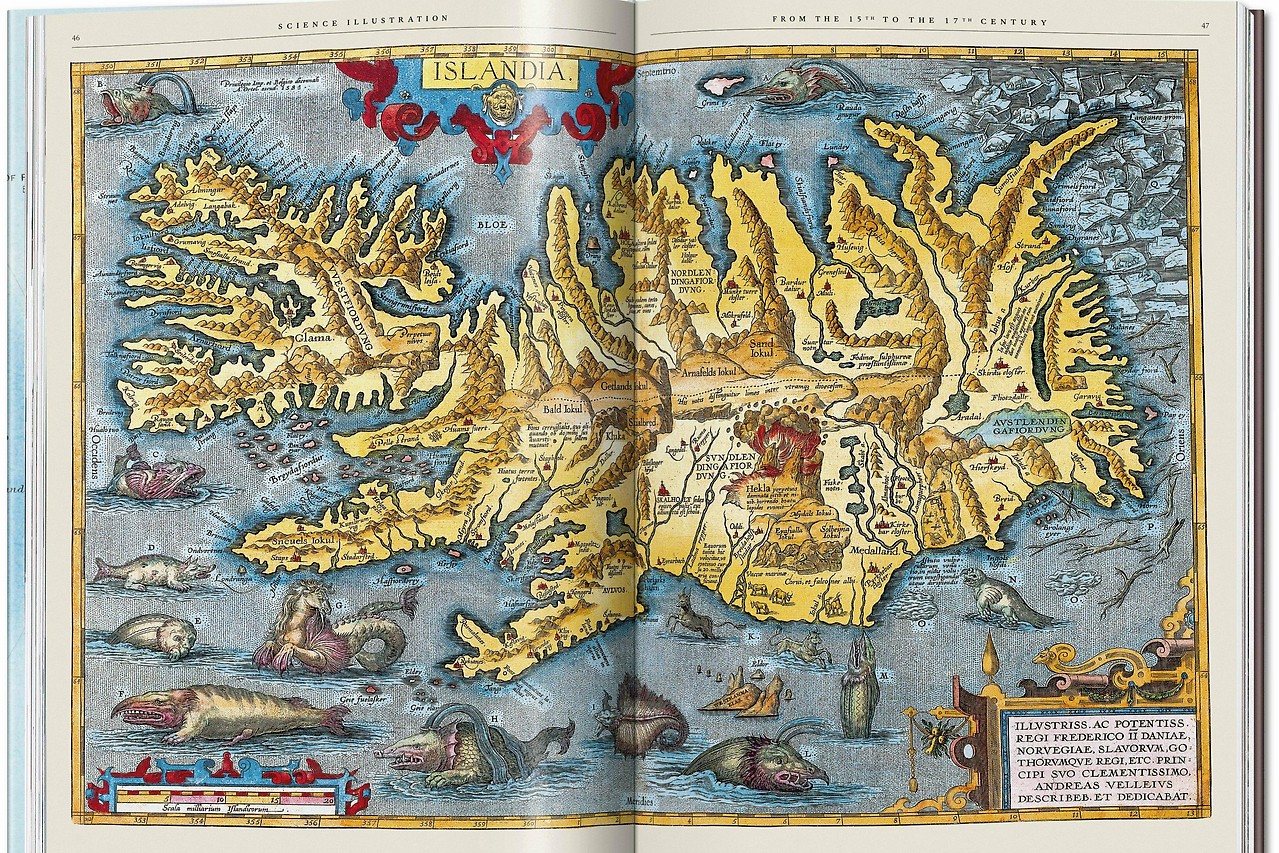

With scientific illustrations, the more complex and colorful they are designed, the more likely they are to be produced for the general public. It is precisely there that the distinction between illustration and art becomes thin – and some “knowledge” is so outdated that its depiction stimulates the imagination rather than illustrates knowledge. Such is the case with a map of Iceland from Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1585), where sea monsters surround it, communicating the island as a dangerous area rather than accurately describing its geography.

Change of imaginary worlds

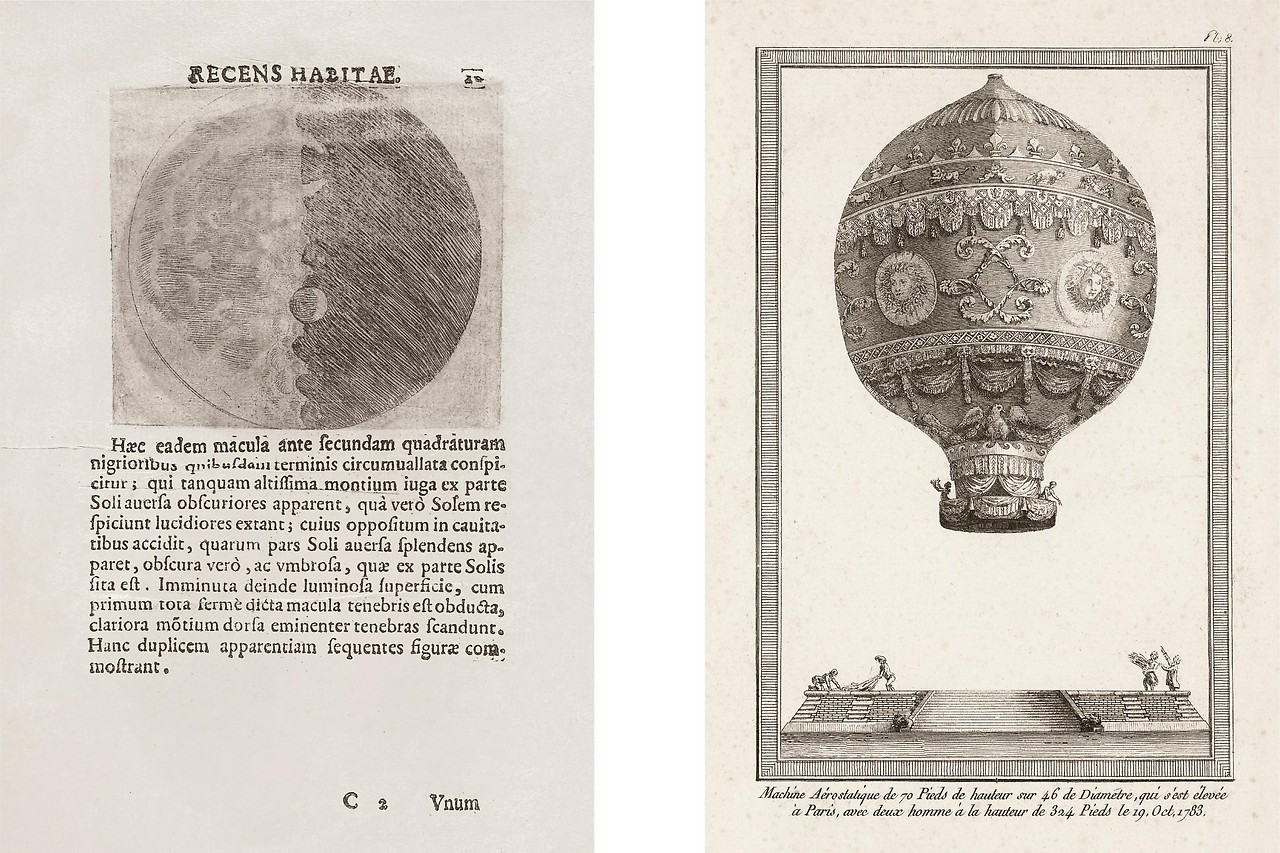

In general, breaks in the imaginary worlds of earlier times can be understood on the basis of the illustrations collected in the volume. Galileo Galileo’s sketches of the moon in his “Siderius Nuntius” (1610) were made following he had built more than 60 prototypes and was able to build a telescope that made 20x magnification possible has an irregular and cratered surface.

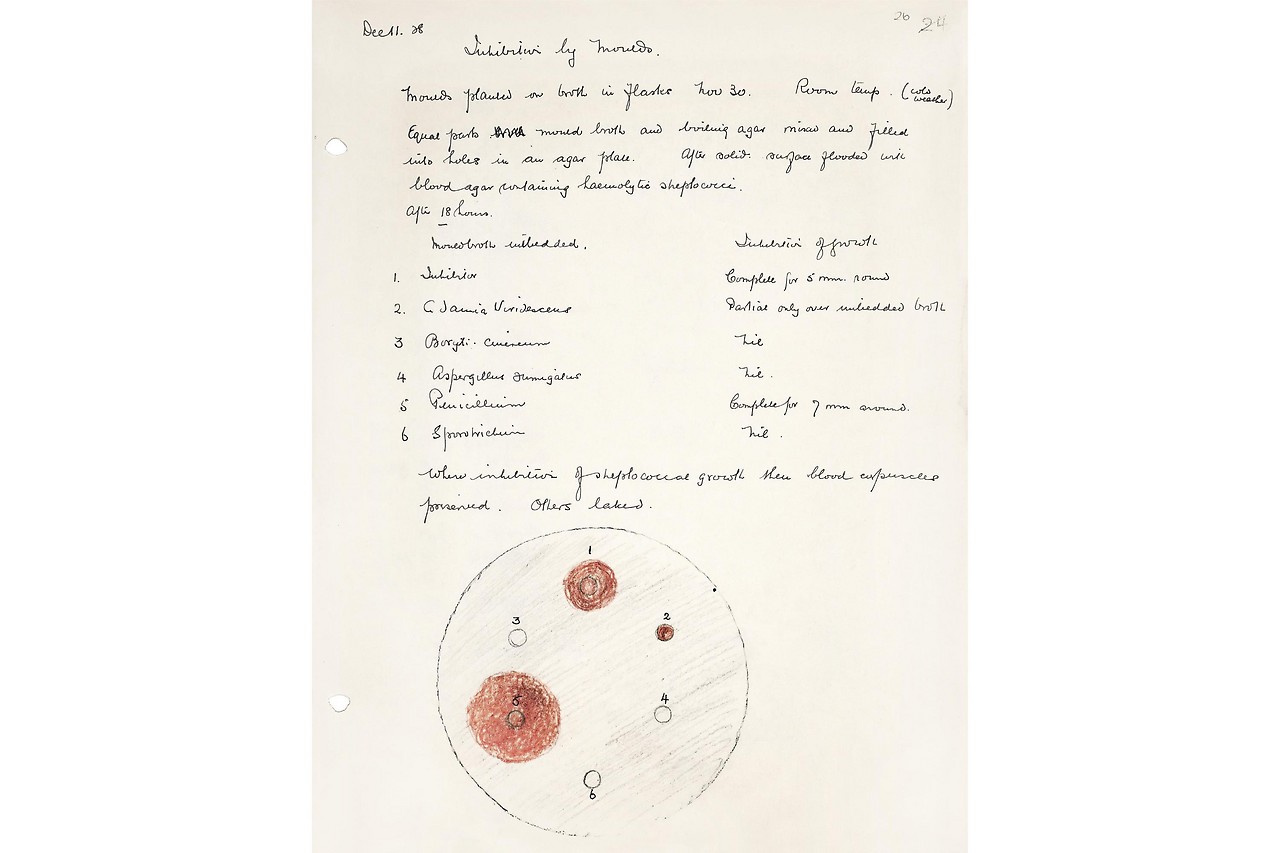

This expansion into space corresponds to another space that is significantly smaller than previously known: In 1665 Robert Hooke published the results of his experiments with a microscope – according to Escardo, his “Micrographia” became the first popular scientific bestseller in which the English scientist used the term “cell “ coined. Inside is one of the author’s favorite illustrations, a detailed sketch of a flea: “People at the time found it incredibly fascinating to see such a small creature enlarged.”

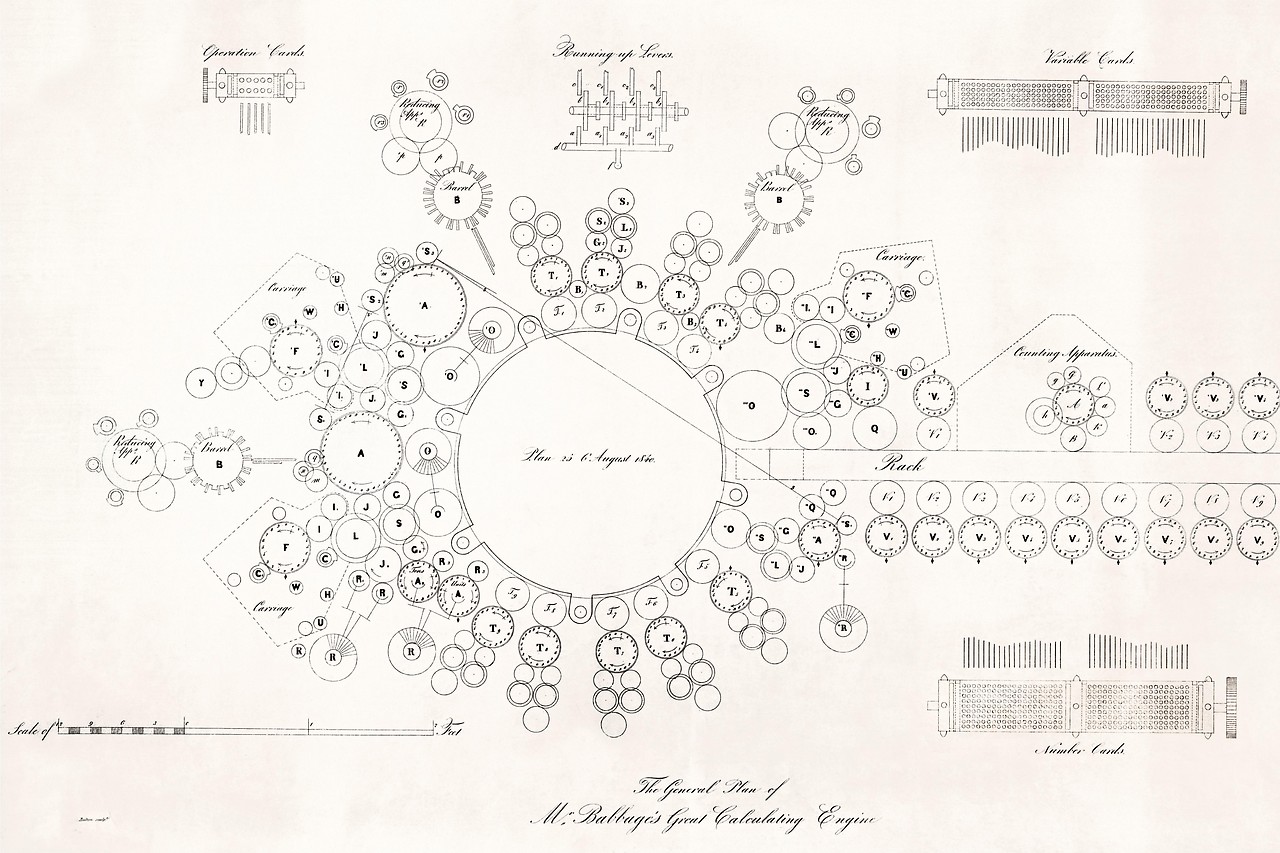

All too often, what was sketched in pictures was on the verge of being credible for contemporaries: This was certainly true of the first automatic robots by inventor Jacques de Vaucanson in the mid-18th century, as was the depiction of the first manned flight in a hot-air balloon by the Brothers Joseph and Jacques Montgolfier 1783 and the technical sketches for the first attempts at radio communication by the engineer Nikola Tesla 1896.

illustration and imagination

While illustration often conveys knowledge gained, in other areas it operates at the origin of scientific ideas, according to Escardo. The sketch is not only at the beginning of the development process in technology, the building also follows the design in architecture.

When asked regarding the most successful scientific illustration, she refers to the Russian chemist Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev, who in 1869 presented the 63 chemical elements known at the time in his periodic table – although he left room in his illustration for those elements whose existence he was able to calculate before they were discovered . Knowledge, as Escardo makes clear with its historical longitudinal section, required and still requires the power of the visual, especially if it is to be conveyed beyond a small circle of specialists.