But for French researcher Bruno Lemaitre, the fruit fly has been an obsession since the first time he saw it under a microscope.

“When I started biology, we usually studied cells or molecules, but when I had this little fly under the microscope, I thought it was very beautiful and interesting,” he told the BBC’s Outlook programme.

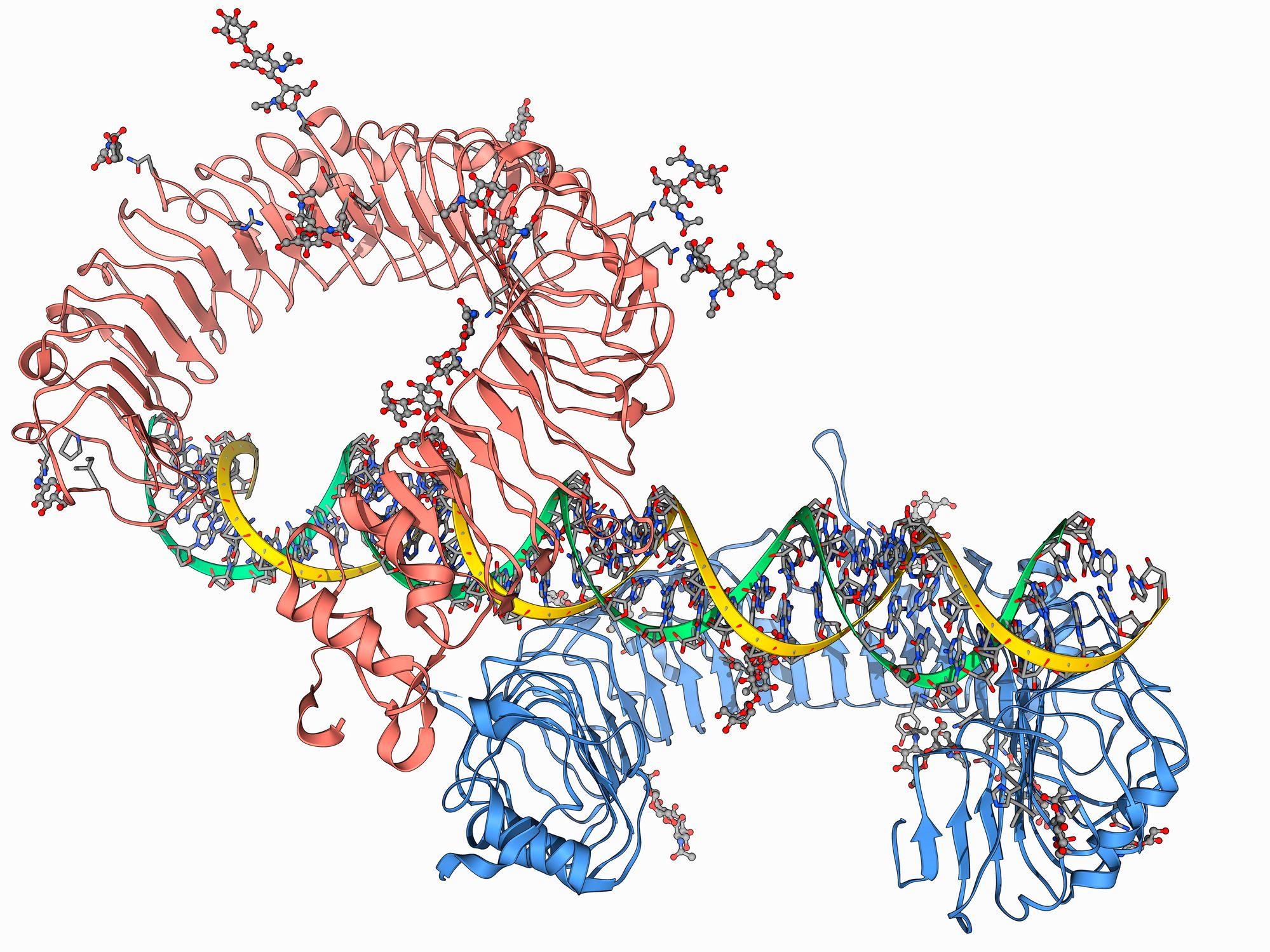

His obsessive curiosity regarding this insect led Lemaitre to make an important scientific discovery: that of how genes, known as toll-like receptors, are responsible for identifying an infection in the body and activating the immune response to combat it.

As expected, the discovery generated a stir in the scientific community and his work ended up being selected as a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2011.

But instead of him receiving the award, or being included as one of the main authors of the work, all the credit went to the person who wrote the scientific study: the head of the unit in which Lemaitre worked.

Today, Lemaitre is dedicated to studying narcissistic personalities and wrote a book titled “An Essay on Science and Narcissism,” and says he is at peace with what happened.

But getting to this point was not easy.

Interest in everything

Lemaitre remembers that as a child he would have loved to be an encyclopedist: to be able to learn everything he might regarding the world around him.

“I was also curious to understand, scientific knowledge interested me a lot. At first I wanted to learn everything regarding astronomy, physics and biology. But at some point I realized that it would be impossible, that I had to focus on one thing and the fruit fly was the object of my passion.”says Lemaitre.

Growing up as a shy child in a house with many brothers and sisters, Lemaitre says he spent a lot of time collecting things, including insects.

“Somehow, my passion for insects brought me into contact with other people and gave me some recognition within my family. My parents were proud of me, some friends told me that they were fascinated by my room, which was full of stones and insects.”

His ability took him to Paris, where he learned other aspects of science.

“Fight for power”

For Professor Lemaitre, it is still difficult to talk regarding what he found when he arrived at the “City of Light”: “How do I say it? “The research structure in France and in French universities is relatively complicated, with a large number of administrative layers.”

“I discovered that professors do not necessarily choose the best students or that professors often had their wives hired in the laboratory. Many cases of favoritism. Maybe I was very sensitive to that but I quickly felt that academic research was not the simple pursuit of knowledge or trying to do the best.”

“It was a fight for power, for jobs, for recognition. Suddenly I was a little naive when I came across this very human aspect in research because, following all, it is in all human dimensions and all communities.”

In the midst of that environment, he found a group of researchers that needed an intern to collaborate on fruit fly studies.

He continued to delve into his new passion, working with Dr Michael Ashburner’s team at the University of Cambridge, and obtained his PhD. Furthermore, during this time he met his wife, of Lebanese origin, and started a family, which required that his search for his next job be limited to the vicinity of Paris.

Of flies and men

There are regarding 1,500 species of flies Drosophila, which we call the fruit fly. It is an animal that has evolved to benefit from the fruits that we grow, and has been the star of several Nobel Prizes.

So much so that the Nobel Foundation recognizes its role: “The Drosophila melanogaster It is used in laboratories around the world and has been integral to the work of many Nobel laureates.”.

“The Drosophila It has many advantages in the laboratory. They have short generation times, and are easy and cheap to breed. In fact, the Drosophila “It is so easy to reproduce that they have been bred on a space shuttle to understand how space flight might affect the human immune system.”

When Professor Lemaitre went to work in a small laboratory on the outskirts of Paris, directed by Professor Jules Hoffman, He says that “he was investigating the immune system of flies, but without looking at the genetic component.”

“Genetics was my area of knowledge and I knew that genetics had been very powerful in understanding other issues. So I fell in love, I said to myself ‘here you can discover something, you can find a place to exist’.”

“We must understand that science always has a collective aspect. You will never be the first person to work on something, and there will always be individuals who influence you. But there is always room for an individual who can compile the information in a new way. “For me it was understanding how fruit flies responded to infections using genetics.”.

The discovery

Although the laboratory did not have much recognition, Lemaitre was content with the great attraction that studying how flies defended themselves from infection represented for him. But his first year in the lab was full of “necessary” failures.

Lemaitre says that, during those months of failures, the laboratory lost interest in the genetics team and he was left working with a colleague, often discussing discoveries among themselves, without necessarily discussing them with his superiors.

He says that the director of the institute, Hoffman, gave a certain autonomy to his teams and remained on trips outside the city obtaining funds for that institution.

But when Lemaitre discovered that by removing the toll receptors from some flies, their immune systems were no longer able to identify an infection and they died, he realized he had found something important.

“I would say that in that article I played a leadership role. “You have to understand that the discovery of toll receptors was not a ‘eureka’ moment in which someone saw how everything worked from the beginning.”

“Tolls were discovered by researchers from Tübingen, Germany. The molecular characterization was done by an important woman in the field called Catherine Anderson. “My part and that of my team was to show the role of tolls in the immune response.”

Lemaitre reported the results to the head of the institute, Dr. Hoffman, who took on the task of writing the research given his extensive experience with the scientific community.

“At first, I wrote the results with the help of my colleague, but then my boss, who wrote better, played a more important role. I appreciated that when you have problems with writing, someone can inject some style into the discovery, that is important.”

The study was published in a medical journal known as Cell.

The Nobel Prize

Fifteen years later, the study on the role of tolls in the immune response had opened the doors for other scientists to begin studying this mechanism in mammals.

Lemaitre had left Hoffman’s laboratory to found his own and there was still uncertainty in the scientific community regarding who would take credit for the discovery of the role of tolls in the immune system.

It was when the Nobel Prize announced that the winner of the Medicine prize was Jules Hoffman.

“You have to understand that these Nobel Prize winners have a political side. By giving a Nobel to work on the fruit fly, they were validating the work in the field I worked in, so I was relieved when I heard regarding the award.”

“But at the same time I was frustrated, hurt.”

“I felt that I had contributed more than him and he had received the Nobel, even though he had helped make it visible and had contributed his knowledge to the development of the laboratory.”

The Outlook program contacted Jules Hoffman, who categorically denied appropriating anyone else’s work or having been closely involved with Lemaitre’s work. On the contrary, he claimed to have been happy when he learned of the scientist’s progress and said that he had two chief researchers who helped him keep up to date with what was happening with his more than 50 scientists.

Regarding the fly experiments, he did recognize that they had been directly carried out by Lemaitre.

In fact, during his award acceptance speech, Hoffman mentioned Lemaitre’s name, but the scientist says it wasn’t enough.

The doubt

With the announcement of the award, Lemaitre says he began receiving calls of support from colleagues, and remembers one in particular.

“I was contacted by an Englishman who told me that he had been an advisor for the Nobel Prize and admitted that this prize had generated many doubts, that not everyone was satisfied with the nomination of Jules Hoffman, who had not always been seen as a researcher but as “a figure that gave visibility.”

“He encouraged me to write a blog in which I tried to explain my contribution to the discovery process. I published the blog and it was a very stressful time in my life. He did not have the strength to claim full authorship, as several people had received credit. But I wrote it to reveal the realities of the investigation.”

The publication generated controversy in the scientific community and put an end to relations between Hoffman and Lemaitre. But for Lemaitre it was necessary.

“In the end I did receive some recognition, I am a professor at a university in Switzerland, but there are some who do not receive any recognition”assures Lemaitre.

He says that delving into the psychological analysis of narcissistic personalities has brought him some understanding of the situation he went through.

“When you go through an experience like this, you need to explore other areas of science, such as psychology, to understand better. That brings some peace. And I received part of my recognition despite my frustration.”

Although as a good scientist, he says that he is left wondering what would have happened if he had acted differently: “I have always wondered something: if the normal attitude of someone in my position would have been to accept with modesty that the boss takes all the recognition and wait my turn.”

“I felt good, but I might have ended up paying the price. Who knows”.

* This is an adaptation of an episode of the BBC program Outlook, which you can find in its original English, here.

Click here to read more stories from BBC News World.

You can also follow us on YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, X, Facebook and in our new whatsapp channelwhere you will find breaking news and our best content.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.

#key #discovery #win #Nobel #boss #prize