2023-08-22 08:00:00

Although the history of apala music is somewhat difficult to unravel, its creation and popularity are forever associated with the late and legendary Haruna Ishola. Born in 1919 in Igbaire Oko-Sopin, a village located in the state of Ijebu-Igbo (today Ogun), Haruna Ishola Adebayo Bello, better known as “Baba Ngani Agba”, launched into music as soon as he was young age, and will be until his death in 1983, considered the father of apala music, achieving enormous success both locally and internationally.

Some claim that the apala originated in Ede, a town in southwestern Nigeria where the traditional account traces the genesis of this style to the year 1938, when a man named Balogun and his son Tijani began to make a name as apala singers. Another popular version affirms that this music already existed before this date – a certain Ajadi Ilorin having become a specialist in it since 1930. Finally, a last theory supposes that the apala would come from different branches of the Yoruba community, which would explain the diversity of styles that this music offers: “apala san-an”, “apala songa”, “apala igunnu”, among many others. Apala, like fuji music, developed as a style of improvisation from were; it is moreover under the name of “ere fowo beti” that it was first designated within the Yoruba Muslim community.

Therefollowing, and before Haruna Ishola gave the genre its final name in 1947, it was known as “oshugbo” and “area”. The genre’s founder’s own son, Musiliu “Haruna” Ishola, who has continued to carry on his father’s legacy as an apala musician, also revealed in an interview that his grandfather and ancestors used the term “ewele”. On this occasion, he also clarified that the music was not yet accompanied by drums, until his father came into contact with a drummer, following which he decided to incorporate drums and use the term “apala”.

Apala music is mainly composed of instruments such as the shekere (calabash rattle), agidigbo (thumb piano), and agogo (bell), as well as talking drums such as the gangan. A highly percussive music, apala was created as a form of cultural rebellion to the British Empire’s colonial rule over Nigeria, which did not end until 1960 when the country gained independence. Going once morest the trend of the time, apala performers resisted the incorporation of Western instruments into the genre. At the same time, the genre has gradually been stripped of its religious connotations over the years, gaining in popularity as a result. Without renouncing its African values, the apala began to draw inspiration from other genres such as Cuban music, adopting instruments such as the claves, the maracas and the ogido – locally known as akuba, it takes the form of a conga drum, larger in size, thus offering a wider range of sounds.

Although Ishola was introduced to singing by his father, an essential figure he lost in his early youth, it was not until 1947, at the age of 28, that the young man trained at the orfèvrerie moved to Osogbo to devote himself to music and form his first apala group. It was then that Ishola’s musical career officially and publicly started, with a first album entitled Orimolusi Adeboye, which was released in 1948 on the occasion of the coronation of a powerful “Oba” (king) in Ijebu-Igbo. If the label is British – His Master’s Voice (HMV) – the album will have little commercial impact and will not allow Haruna Ishola to gain fame. This did not prevent him from traveling all over the place as a performing artist, quickly making him one of the most requested artists by the Nigerian elites and social circles during Owambe parties. He reigned supreme throughout the 1950s, traveling the South West region with his apala group, with a repertoire that would leave a lasting mark on Nigerian high society with his musical repertoire.

Things took an even more favorable turn for the singer in 1955, when he recorded a new version of his 1948 album, following the death of Oba Adeboye in a tragic accident. The album peaked at number one, and Haruna Ishola was finally acclaimed, finally becoming Nigeria’s most popular and revered apala musician. It is through his very personal use of Yoruba proverbs and Koranic recitations in his songs that he made a unique reputation. Throughout her career, Haruna Ishola refrained from using Western musical instruments, as is usually the case for apala performers. His tenacity will have largely contributed to his success, in resonance with the people deeply attached to sharing local music devoid of any Western influence. In sum, Ishola’s apala was a way of challenging British colonial rule.

At his concerts, Haruna Ishola often sat alongside his band, a choir of singers and musicians specializing in the gangan, agogo, akuba and agidigbo (lamellophone), instruments that played a essential role in the unique sound of the apala. Ishola was exceptionally gifted in songs of praise and captivated his audience with the power of his voice. As his fame spread across the continent, the apala’s father became more than a musician: he was simultaneously an observer of society, a philanthropist and a chronicler of historical events. His lyrics are thought-provoking as he meditates on the meaning of life and other profound matters, singing in the form of parables and anecdotes. We hear it in particular on a record like What a healer where he declaims « If the fire enters, the darkness will escape. Fire helps the enemy not to burn »which means : “When the light enters, it drives out the darkness. When fire burns, enemies are set ablaze. »

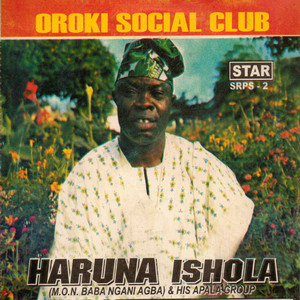

In 1960, following Nigeria gained its independence, Ishola released a song titled in English “Punctuality is the Soul of Business” on Decca Records (a British record company, in new, which would become a subsidiary of Universal Music Group in 1980). It was also on Decca Records that he released his best-selling album in 1971, Social Club song, which would have sold more than five million copies. The title is a direct reference to the “Oroki Social Club”, a political movement born in the 1960s, when the government led by Akintola continued to oppress the supporters of his 1962 electoral opponent, Chief Obafemi Awolowo. . Among the disciples of Obafemi Awolowo, 51 young people from the city of Osogbo, strongly welded and politicized, formed themselves into a political group. It was during a debate during which they were developing a plan to become more involved in the affairs of the city, that they decided to give this name to their “club”. Therefollowing, several members of the Oroki Social Club will become influential politicians who will largely contribute to the development of Osogbo and the liberal turn that the city will take. These young activists are recognized and respected by both elites and ordinary citizens for their attitude as members of a social club and for the impact they have on the socio-political affairs of Osogbo. The title track of Ishola’s album thus pays homage to the prestigious nightclub which is also the political headquarters of Osogbo, where Ishola often performed in front of enthusiastic audiences during performances which lasted four at ten o’clock. On this track, he sings: “Students, come and dance our music, apala is very easy Phoenician. » The massive success of the album will provide the club and its founding members with significant popularity.

Haruna Ishola will also be one of the first Nigerian artists and the first apala musician to go on a major musical tour around the world, including France, Sweden, the United States, the United Kingdom, India. Italy and West Germany. On his return from the London tour, he released the album On my way to Londonon which he sings « On my way to London ko s’ewu rara », which means: “On my way to London, there was no danger. Thanks to the continued interest of the public in his music, Haruna Ishola will be considered one of the richest Nigerian musicians of his time, arousing in passing the admiration of Westerners, amazed by the wealth and the ease of the African artist. He goes regularly to London where he received a more than cordial welcome from several bank directors.

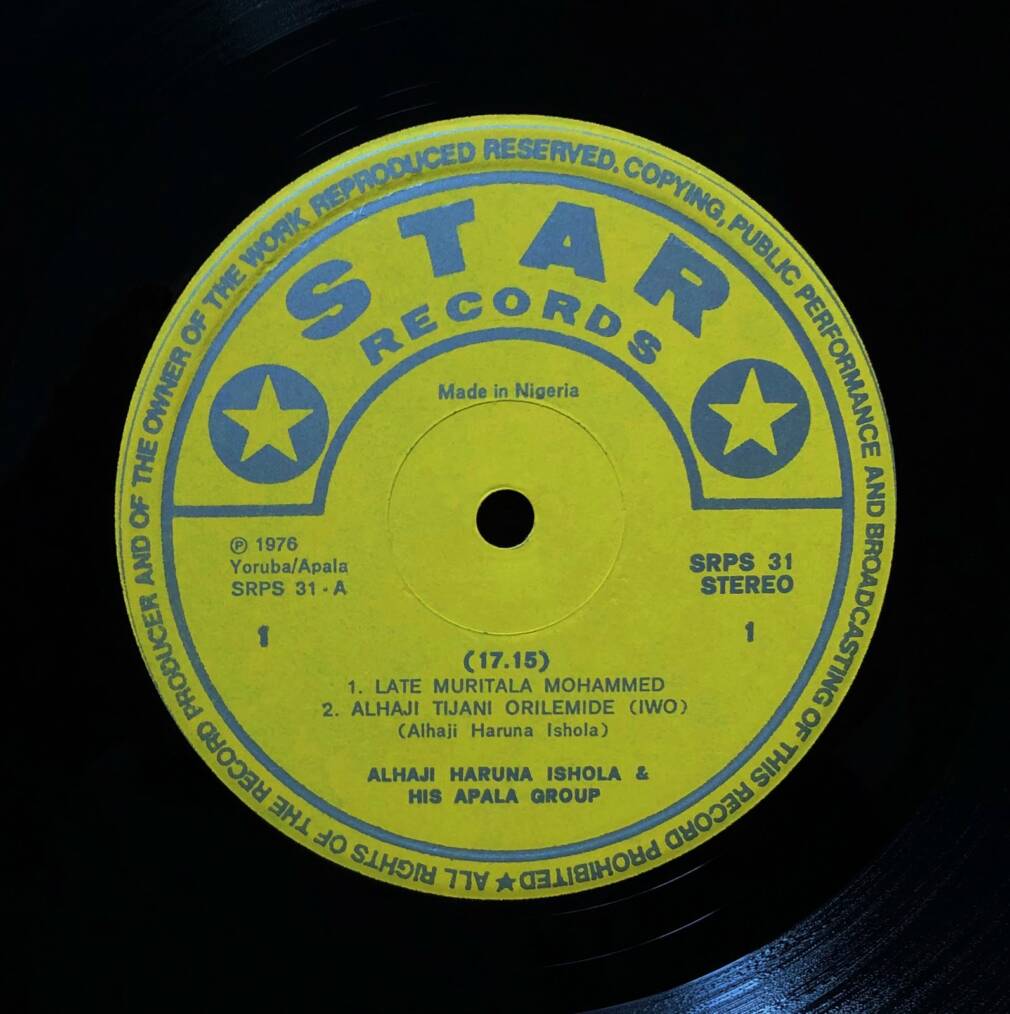

In 1969, Haruna Ishola founded the label STAR Records Ltd. in partnership with the famous juju musician, IK Dairo. First label belonging entirely to African artists, it is thanks to him that Haruna Ishola will continue to develop her artistic career, publishing records such as Who God Made For, Good luck with Tomi Dakun’s son et Information on Our Own. In the early days of the label, most records were pressed by Record Manufactures Nigeria Ltd. or Decca (in London), before the musician-entrepreneur finally founded his own record company in 1979, Phonodisk, with its own pressing factory and recording studio. The label will have welcomed many emerging artists who then benefit from a professional structure. It should be noted that before founding STAR Records, Haruna Ishola had first created a label in partnership with Nurudeen Alowonle, general manager of the company, as well as with two other businessmen. The collaboration ends following the general manager is caught in the act of embezzling revenue from record sales. After the dissolution of the society, Haruna Ishola and Nurudeen Alowonle would engage in an endless legal battle over the right to use the name of the society.

The music industry changed profoundly in the 1980s, with the proliferation of digital music caused by regular concert bans. However, even at this time, Haruna Ishola continues to thrive and continues to be widely recognized as the pioneer of apala. In 1981, he even became a “Member of the Order of Niger” (MON) in recognition of his prowess, a title bestowed on him by Alhaji Shehu Shagari, then President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Although he had competition from other artists like Kasunmu Adio, Sefiu Ayan or Ajao Oru (supposedly the first African artist to record an album for a British record company, Philips Recording Company), the only other name that reached commercial heights and rivaled Haruna Ishola in apala music is that of Ayinla Omowura. The latter frankly argued with Haruna Ishola before later recognizing the superiority of the veteran. Haruna Ishola would pass away in 1983 and his son, Musiliu “Haruna” Ishola, would carry on his legacy, experiencing huge success in the 1990s and early 2000s, following in his father’s exact footsteps.

While apala experienced a sharp decline in the mid-2000s, an era that saw Nigerian music change in sound and style, neo-fuji artists like Terry Apala, Qdot and Seyi Vibez would continue to infuse elements of apala in their own music. A specificity particularly evident in the cadence of the songs, but also in the ingenious use of the Yoruba language to recite captivating poetic texts, and tell stories that fascinate listeners, once once more restoring the image of Haruna Ishola and recalling the influence of apala on contemporary Nigerian music.

1693053389

#Haruna #Ishola #father #apala #music