Han Kang, the South Korean author renowned for her powerful prose and haunting narratives, is a figure who prefers to let her writing speak for itself. While her rise to international acclaim with the International Booker Prize-winning novel “The Vegetarian” in 2016 marked a turning point in her career, she remains a private individual, rarely offering insights into her personal life. This quietude is reflected in the limited facts readily available about her biography.

Following her impactful Nobel Prize win in 2024, it was widely reported in South Korean media that she was married to literary critic Hong Yong-hee. This information proved to be outdated. The couple has been divorced for years, adding another layer of mystery to Kang’s persona. kang’s novels frequently enough explore complex themes of identity, trauma, and societal expectations, drawing parallels with her own experiences. Readers intrigued by the parallels between her characters and her life story are often left wanting more, creating an air of intrigue around the author.

Despite the desire for personal revelations, Kang’s literary voice remains the primary focus. Her novels, such as “Human Acts,” published in 2017, continue to captivate readers with their raw honesty and unflinching explorations of the human condition. Ultimately, it is through her captivating storytelling that Han Kang truly connects with her audience, leaving them to piece together the intricate tapestry of her life through the prism of her words.

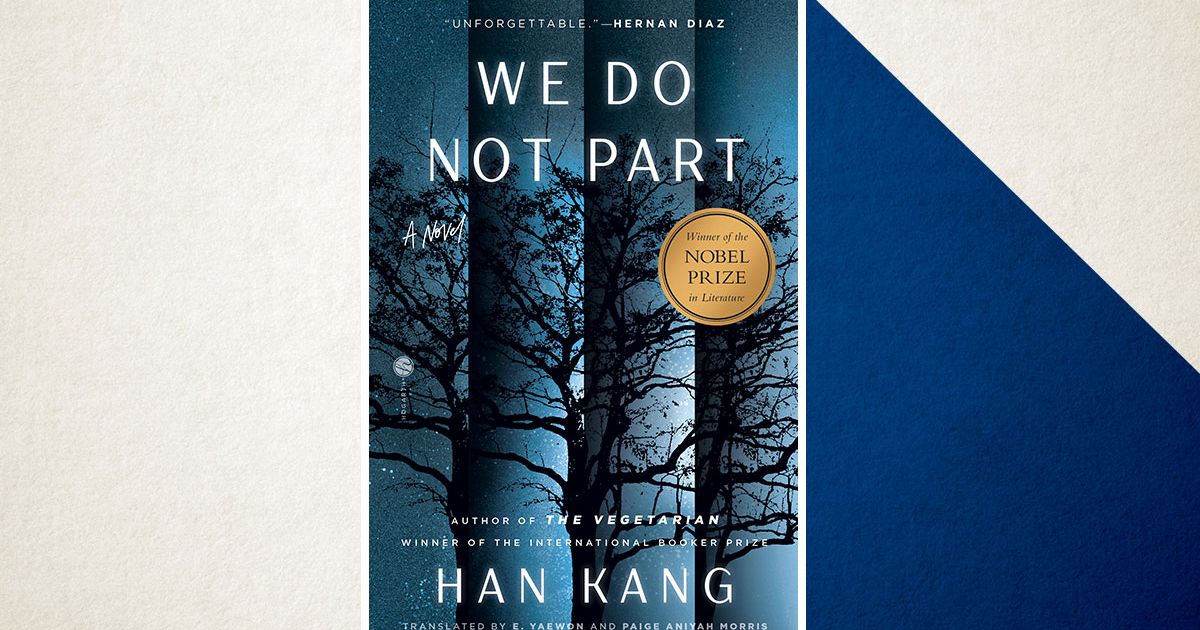

Han Kang’s latest novel, We Do not Part, explores the fragile nature of existence through the lens of a writer grappling with profound inner turmoil. Originally published in 2021 and recently translated by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris,the book delves into the depths of human suffering and the crippling effects of trauma.

Kyungha, the protagonist and narrator, is haunted by disturbing nightmares – visions of murderers, massacres, and women fleeing violence into the abyss of a well. A recurring dream of a rising sea engulfing a valley of black tree trunks particularly weighs on her, symbolizing a growing sense of despair and isolation. Insomnia, migraines, and debilitating abdominal spasms further torment her, pushing her to the brink of collapse.

She seeks refuge in a solitary apartment outside Seoul, her days consumed by a monotonous cycle of ordering takeout and purging it, a stark reflection of her emotional emptiness. “A desolate boundary,” Kyungha reflects,“had formed between the world and me,” indicating a profound disconnection from everything around her.

The concept of fragmentation permeates Han’s literary world.her characters frequently enough experience a profound unraveling, losing their ability to speak, see, eat, sleep, or even remember. This disintegration is not simply a result of external forces; it is indeed an outward manifestation of an inner turmoil that consumes them.Kyungha, once a stable individual with a family and a writing career, has undergone a radical transformation over the course of four years. She describes her severance from her past life as “a snail coming out of its shell to push along a knife’s edge.”

Underlying this transformation is a haunting connection to the Gwangju Uprising, a pivotal event in South Korean history. Like Han herself, Kyungha wrote a book about the massacre, where around 2,000 students and workers were brutally killed by the Korean army in 1980. The memories and emotions associated with this tragedy intertwine with her nightmares, further fueling her psychological distress.

Haunted by the past and tormented by her present, Kyungha grapples with a pervasive sense of vulnerability. “Life was exceedingly vulnerable,” she observes, “The flesh, organs, bones, breaths passing before my eyes all held within them the potential to snap, to cease — so easily, and by a single decision.” Her words echo the fragility of existence, highlighting the ever-present threat of violence, both physical and emotional, that permeates human experience.

Exploring Trauma Through Art: Han Kang’s ”We Do Not Part”

South Korean novelist Han Kang,known for her haunting exploration of trauma in works like “Human Acts,” returns with a new novel,”we Do Not Part.” This deeply affecting story weaves together personal grief and national history, focusing on the enduring legacy of the Jeju Uprising, a brutal massacre that took place in 1948.

Kyungha, the novel’s protagonist, is struggling to cope with her own brush with death.While grappling with personal loss, she receives a desperate plea for help from her friend Inseon. Inseon, living in isolation on Jeju Island, has suffered an accident, leaving her hospitalized and unable to care for her beloved budgie, Ama. Kyungha, weakened but unable to ignore Inseon’s plight, embarks on a perilous journey to jeju, facing a blizzard that mirrors the harsh realities of the island’s history.

“How to make art about such an atrocity?” Han asks in the novel, reflecting on her previous work, “Human Acts.” While that book offered multiple perspectives on the Gwangju massacre, Han seems to feel this approach falls short. In “We Do Not Part,” Kyungha confesses to omitting particularly gruesome details from her own book about Gwangju,such as ”the people rushed to emergency rooms on improvised stretchers,burn blisters on their faces,their bodies doused in white paint from head to toe to prevent identification.” Faced with the sheer horror of the event, she admits to turning away.

“We Do Not Part” appears to be an attempt to confront this past head-on.Han fills the narrative with documents, memories, photographs, and facts, creating a complete account of the Jeju massacres. Yet, instead of sensationalizing the violence, Han focuses intently on Kyungha’s journey, creating a compelling blend of concrete reality and unsettling mystery. Upon arriving at Inseon’s home, Kyungha finds Ama dead, and she buries the bird. Upon waking,however,Ama is alive,and Inseon is asleep in the workshop. Are these glimpses into the afterlife, hallucinations, or fragments of memory? Is Kyungha, perhaps, dead herself, lost in a blizzard or alone in her apartment, her spirit wandering?

The novel unfolds as a tapestry woven from personal and national histories. Inseon’s mother survived the massacre by sheer chance, while her father spent years in hiding, eventually arrested and imprisoned.Both returned to their village, rebuilding their lives while carrying the trauma within them. They retreated to caves, haunted by memories, sleeping with a saw beneath their mattresses, as if prepared for any further violence.

In Han Kang’s masterful novel, We Do Not Part, the ever-present specter of violence lingers after the cessation of wartime conflict. This haunting reality permeates the lives of the characters, leaving them forever marked by the trauma of the past. Violence, as Han portrays it, isn’t a singular event, but rather a constant tension that weaves itself into the fabric of everyday existence.

The family in the novel grapples with this relentless weight of history. Each member carries the scars of conflict, both physical and emotional. Kyungha, the protagonist, seems to be fracturing under the strain. She struggles to construct a barrier around herself, a shield from the past that threatens to consume her.

“I don’t want to open it,” she confesses, referring to Inseon’s collection – a repository of memories that threaten to shatter her fragile peace. “I’m not the least bit curious.” However, despite her desperate attempts to shut out the past, Kyungha is drawn inexorably into its web.

Han masterfully blends fact and fiction, weaving together threads of history and personal narrative. We Do Not Part gives voice to the unsung stories of survival, offering a glimpse into the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable horror. The narrative suspends time,blurring the lines between past and present.The novel is both a poignant exploration of grief and a celebration of the enduring human capacity for love and connection. It’s an intricate tapestry of sorrow and hope, leaving an indelible mark on the reader’s soul.

Through evocative imagery and powerful storytelling, Han Kang invites us to confront the enduring legacies of violence and to remember the importance of human connection in a world consumed by darkness. Like the bird that Han often uses as a metaphor, We Do Not part soars with splendid vulnerability, a solid form navigating the turbulent currents of history.

How does Han Kang’s approach to exploring trauma in “We Do Not Part” differ from her previous work, “Human Acts”?

Archyde Interview: Han Kang on “We Do Not Part” and Exploring Trauma

archyde: Welcome, Han Kang, to Archyde. Your latest novel, “We Do Not Part,” delves deeply into trauma and its enduring effects. What inspired you to explore these themes in your new work?

Han Kang: Thank you for having me. I’ve always been drawn to exploring the human condition, particularly the ways in which we experience pain, loss, and trauma. In “we Do Not Part,” I wanted to explore how personal grief can intertwine with national history, and how the past continues to haunt us. The Jeju Uprising, a brutal massacre that occurred in 1948, served as a poignant backdrop for this exploration.

Archyde: Your protagonist, Kyungha, is a writer haunted by her own experiences and the Gwangju Massacre. How much of Kyungha’s journey reflects your own experiences or feelings?

han kang: While kyungha is a fictional character, there are indeed aspects of her journey that resonate with my own experiences. Like Kyungha, I’ve grappled with the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre, both in my personal life and my writing. Though, it’s vital to note that Kyungha’s story is not a direct reflection of my life. I’ve taken creative liberties to craft a narrative that explores these themes in a deeper and more profound way.

Archyde: In “We Do Not Part,” you employ a multi-layered narrative structure, incorporating documents, memories, and photographs. What compelled you to use this approach?

Han kang: I wanted the narrative structure to mirror the fragmented nature of Kyungha’s experience, as well as the fragmented nature of collective memory and history. By incorporating various forms of text and visual elements, I aimed to create a more immersive and holistic reading experience that reflects the complexity of trauma and its impacts.

Archyde: Your previous novel, “Human Acts,” offered multiple perspectives on the Gwangju Massacre. Did your approach in “We Do Not Part” differ due to your feeling that the previous approach “falls short”?

Han Kang: “Human Acts” was an attempt to explore the Gwangju Massacre through a multiplicity of voices and experiences. With “We Do Not Part,” I wanted to take a different approach. I felt the need to confront the atrocities of the past head-on, without necessarily filtering them through multiple perspectives. In this novel, I wanted to take a more direct and unflinching look at the horrors of the Jeju Massacre and its enduring effects on those who experienced it.

Archyde: Kyungha reflects on how art can grapple with such atrocities. How do you as an author approach writing about these horrific events without sensationalizing them?

Han Kang: It’s a delicate balance, and one that I continually grapple with as an author. I believe that art has the power to both confront and humanize the most grim realities of our world. To avoid sensationalizing these events, it’s crucial to approach them with empathy, nuance, and a deep respect for the human dignity of those who experienced the trauma. This means seeking to understand and represent the full complexity of their experiences, rather than solely focusing on the most gruesome or shocking details.

Archyde: Thank you, Han Kang, for sharing your thoughts and insights with Archyde.your work continues to captivate readers and prompt important conversations about trauma, history, and the human condition.

Han Kang: Thank you for inviting me to share my thoughts. It’s always a pleasure to discuss my work and its themes with readers.