November 2015: the first French monograph devoted to Georgia O’Keeffe is inaugurated at the Grenoble Museum. Long remained unknown in France, Georgia O’Keeffe is now exhibited at the Center Pompidou in a huge retrospective that spans the entire XXe century. How to explain this late recognition when its reputation is second to none across the Atlantic? Because she was a woman? Without a doubt. Because the fruitfulness of pre-war American art was only recognized very late, at a time when New York was establishing itself as the new scene of modern art, in the image of expressionism abstract displayed by Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko? Certainly. But perhaps also because the work of Georgia O’Keeffe is not easy to apprehend, does not belong to any predefined current and has never openly sought to “form a school”. From her beginnings at the Art Students League in New York to her last works in New Mexico, Georgia O’Keeffe has constantly moved back and forth between figuration and abstraction, thus refusing posterity the temptation to link his work to a current or a predefined artistic movement.

The obsession with the gaze

Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings reflect her perception of things, of shapes, of colors, of the space that surrounds objects. Wherever he vacations, O’Keeffe always strives to capture on canvas the impression of things left on his retina, from the New York skyscrapers to the rugged desert terrain that hugs his Ghost Ranch home ( New Mexico). “Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting came both from within and from without, from her feelings and from the physical qualities of the world”notes Alicia Inez Guzmán in her biography of the American artist (Georgia O’Keeffe, space for freedomFlammarion, 2021).

A nomadic artist, O’Keeffe carries from one place to another this unique look at his own experience of the world. It is this same look that attracted her very early on to photography, more particularly to Le 291, the beating heart of the New York art scene: created in 1905 (at number 291 on Fifth Avenue, from where it draws its nickname), the gallery officially called Littles Galleries of the Photo-Succession is directed by a certain Alfred Stieglitz, whose exhibitions of the European avant-garde are known throughout the Big Apple. It was this same Alfred Stieglitz who, in 1924, would become her husband, following having been the first to exhibit his works. He would produce countless portraits of her – over 300 – earning O’Keeffe the reputation of being the most photographed woman of the century.

American Beauty

Very early on, O’Keeffe showed his independence and his desire to make art his profession. Where most women of her day were encouraged to find a husband following high school, she enrolled in college and considered a career as a teacher, providing some form of financial security to pursue her art. She discovered gallery 291 during her first stay in New York in 1907, but her time had not yet come: not earning enough money to continue her studies and physically weakened, O’Keeffe returned to her family in Charlottesville, Virginia and is regarding to give up painting.

There, she enrolled in university and learned the aesthetic principles advocated by Arthur Wesley Dow: O’Keeffe then refined the harmony of her compositions, focusing as much on reduced subjects as on larger landscapes. . She obtains a teaching post in Texas, in an environment contrasting with the roaring modernity of New York where, during this time, Alfred Stieglitz exposes Picasso, Braque and Marcel Duchamp. All of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work will thus be traversed by this duality between the wide open spaces of plains and canyons, where earth and sky collide in a burning horizon, and the boring verticality of a city like New York.

In 1914, O’Keeffe finally returned to New York to follow Dow’s teachings and feed on the European avant-garde. The death of her mother the following year pushes her to leave town once more. But, a year later, she entrusted a series of abstract charcoal drawings to her friend Anita Pollitzer, who immediately passed them on to Alfred Stieglitz: captivated, he decided, despite the initial reluctance of his future wife, to exhibit his drawings at the 291.

Having left to teach in a small Texan town from 1916 to 1918, O’Keeffe took advantage of his free time to depict the effects of these wide open spaces on his sensitivity, while exchanging regularly with Stieglitz: from this correspondence a fusional relationship was born between the two beings. , who nourish each other with their art. Stieglitz photographs New York in full mutation; he photographs his muse from all possible angles, probes the mystery of his being over the entire surface of his bare and impassive body. A portrait exploded in time that embodies the dream they share of achieving a truly American art (« The Great American Thing », they call it) stripped of European heritage. These photos caused a scandal, but the two artists attached little importance to them.

In the 1920s, Georgia O’Keeffe was then at the top of her game. It was during this same period that she painted, with equal fascination, the skyscrapers bathed in light, which seem to want to defy the universe, and the flowers that she enlarges on the canvas like consecrated temples. with the same vital impetus. But her paintings of flowers are quickly associated with representations of an erotic nature, reminiscent of the portraits taken by Stieglitz, to the great regret of the painter.

The call of the desert

“I made you take the time to look at what I saw and when you took the time to notice my flower, you projected all of your personal associations onto it, and you write on my flower as if I thought and saw what you think and see of the flower – and it is not”, she says to critics who see in her work the expression of a specifically feminine sexuality. O’Keeffe sees in these Freudian interpretations the own projections of his commentators. For her, painting these flowers responds exactly to this same need to transcribe what she perceives and feels in contact with her environment. Flowers, canyons or bones, emerging or decomposed objects, Georgia O’Keeffe applies the same principles of composition and encourages the observer’s gaze to plunge into the unknown that an apparently banal object can convey.

This misunderstanding of the critics of her time coincided with the gap that was to widen between her and Stieglitz from 1929. While she discovered New Mexico, where she felt truly fulfilled, her relationship with Stieglitz gradually split, even if they continue to support each other. It is in the solitude of the desert that Georgia O’Keeffe will henceforth draw her inspiration.

“I discovered that I might say things with colors and shapes that I mightn’t otherwise express. I had no words for it.”

Georgia O’Keeffe multiplies the round trips between the city and its desert. It was a time of crisis for America, which had not recovered from the stock market crash of 1929; it is also the crisis for O’Keeffe, who, following an episode of nervous breakdown in 1933, renews his palette in contact with the ocher earth of New Mexico. In 1934, she fell under the spell of Ghost Ranch, an oasis lost in the middle of tables, where she would stay every summer before buying a house there six years later, which she would soon never leave. Stieglitz’s death in 1946 confirms his desire to settle there for good. Three years later, Georgia O’Keeffe moved permanently to Ghost Ranch, in this “Distant” whose memories she systematically brought back on her canvases once she returned to Lake George (the Stieglitz family home north of New York).

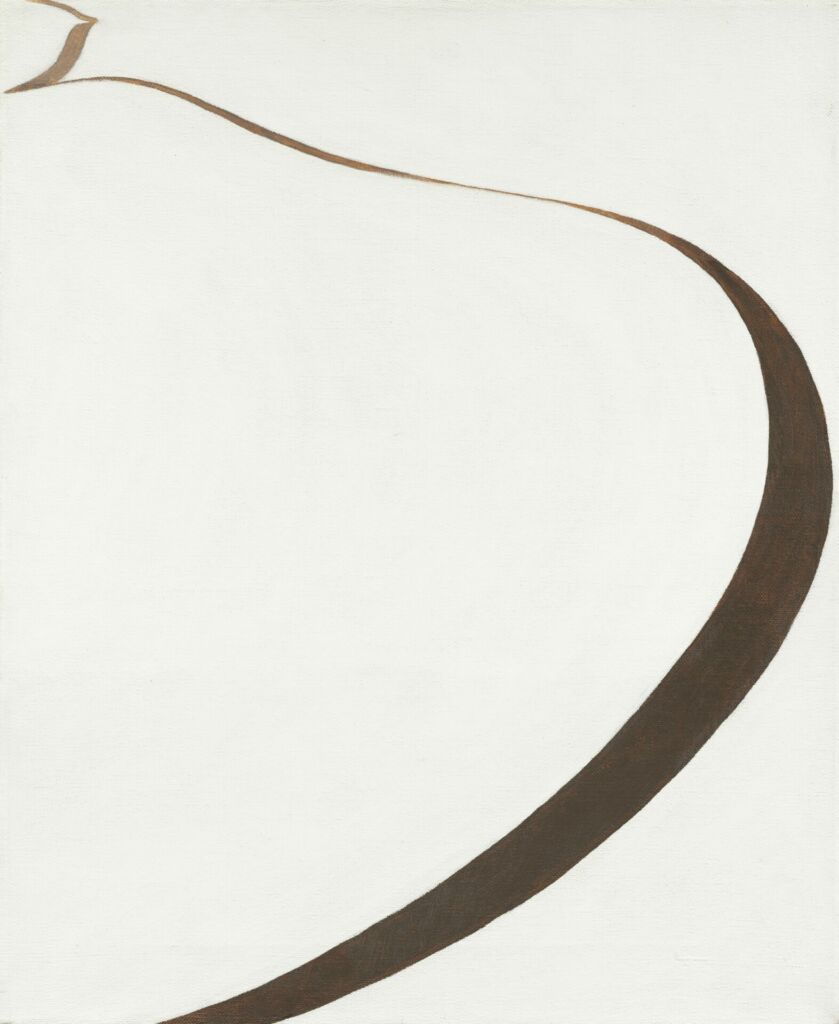

She will then not stop painting what is offered to her: the azure sky, the door opening onto her patio, the waterways, the skulls of animals, the road she sees from her house or the clouds that she observes during her air travels. Over time, his paintings seem to tend towards simpler and simpler forms; small flat colors – squares, circles and curves surrounded by emptiness – replace the overflowing forms of earlier works.

Suffering from macular degeneration, her eyesight deteriorated: almost blind, she continued to paint without assistance until 1972. “Painting had become a reflex, something she did even when her eyes might no longer fully distinguish their subject”, according to Alicia Inez Guzmán. His latest productions then recall the abstract works of his debut, as a final effort of remembrance: for, with Georgia O’Keeffe, art and life were one and the same thing.

Practical information

Georgia O’Keeffe, Centre Pompidou (Paris 4th), until December 6, 2021 – Every day from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. and Thursday until 11 p.m., closed on Tues. – Ticket office here