“I’m not sure that our vision of art really matches our time”wrote Georgia O’Keeffe to the novelist Sherwood Anderson. Thirty-five years following the death of the American artistthe first one retrospective dedicated to him by the Center Pompidou seems to prove him right.

In his monograph Georgia O’Keeffe: an American icon (2021), Marie Gerraut presents Georgia O’Keeffe as a nonconformist artist who rejected purely figurative art to establish her own rules, and, at times, went once morest the modernist canon and the avant-garde ideas of her time .

While the Center Pompidou exhibition mainly associates Georgia O’Keeffe with modern American art of the 1910s and painting of the 1930s, other satellite movements are evoked there, such as the romanticismfrom landscapingfrom minimalismof orientalism and of committed art. Georgia O’Keeffe seems to be a “unique artist, with an unclassifiable work”, to use the words of Marie Gerraut.

Alfred Stieglitz et de Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (2021).

The cult of “hyper”

If in her time, the work of Georgia O’Keeffe seemed difficult to classify, the latest theoretical advances, particularly with regard to the overcoming of modernity, its causes and its modalities, invite us to perceive the artist from a new: that of a visionary prefiguring thehypermodernity.

Hypermodernity, a term popularized by sociologist Gilles Lipovetsky to describe a society weakened by the crises of the twentiethe century, is marked by three notions: loss of identity, urgency and excess, which disfigure reality.

And the artist’s best-known paintings – hyperfocal close-ups of hypertrophic flowers – precisely outline a “cult of the hyper”.

Showing an ambivalent identity

If hypermodernity evokes the disappearance of identity, the work of Georgia O’Keeffe does not seem to fall into this category. The theme of identity is abundant and multiplied under the effect of axial symmetry. His paintings are haunted in particular by the figure of the double, while each brushstroke is duplicated in his paintings, whether buffalo skulls whose shape follows a line of vertical symmetry as in Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills (1935) or landscapes whose colors respond to each other following a line of oblique symmetry as in Nature Forms – Gaspe (1932).

This aesthetic may also symbolize the desire to be a mother of the artist, who had no children. If specularity – i.e. the action of looking into its dimension of fascination – associated with flower petals or buffalo skulls whose shapes recall the female reproductive system, echoes the themes of childbirth, of life and reproduction, the bones can evoke sterility and the death drive, just as much as the desert landscapes dear to the artist, although she breathes life into them through painting.

The painter shows us an ambivalent identity, as fertile as it is destructive.

Abstraction et art hyperfocal

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (2016).

The second pillar of hypermodernity is theemergency ; Georgia O’Keeffe constantly emphasizes the urgency of seeing, through hyperfocal art. Nevertheless, are these very close-ups on details of flowers or bones a matter of abstraction? The etymology of the word “abstract” comes from the Latin abstract which means “separate from”. Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers are indeed extracted from their natural environment and therefore constitute a microcosmic representation which may seem abstract at first sight, but which one cannot help but associate with known forms, often associated to female anatomy.

Yet, as the podcast of the Center Pompidou exhibition points out, Georgia O’Keeffe was fascinated by “the power of the cosmos”, and her works actually form a synthesis of the microcosm and the macrocosm, showing her desire to go beyond the dichotomy opposing the close and the distant, and therefore abstract art and realistic art. The artist even said:

“I’m always surprised how people separate abstraction from realism. Realistic painting is never good if it is not successful from an abstract point of view. »

Georgia O’Keeffe’s work is at the crossroads of representations, but also of senses.

An eminently sensory art

The syncretism at work in the art of Georgia O’Keeffe creates topographic shortcuts (the proximity of a flower makes the viewer aware of the extent of the cosmos), cultural (the bones evoke both pagan relics and the Christian liturgy), and sensory: Georgia O’Keeffe is indeed very inspired by the essay “Spiritual in Art” (1912), in which Vassily Kandinsky – a notorious synesthete – establishes the pictorial foundations of orphism and of theinstrumentalism inherited from René Ghil by declaring in particular that “the colors are the keys of a keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, and the soul is the piano itself, with its many strings, which vibrate”. This enthusiasm for correspondences between the arts is found in synesthesia suggested by the titles of Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings, like Blue and Green Music (1919-1921).

This aesthetic of the shortcut between the arts aligns with the hypermodern concept of urgency, form of hedonism contemporary that pushes the individual to want to see everything, do everything, feel everything simultaneously. In hypermodern theory, this cult of urgency is also associated with that of excess and overflow, which translates into works that extend beyond themselves – beyond their parergonDerrida would say – at Georgia O’Keeffe.

See beyond the frame

If the artist’s close-ups are disturbing, it is as much by the crudeness of their evocations as by the out-of-frame, or the unknown, that they suggest.

Provided by the author

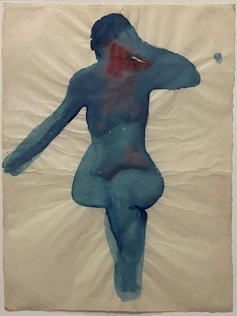

Where does Georgia O’Keeffe’s work stop? Can it really limit itself to the framework that is predefined for it? The texture of the artist’s paintings first suggests a work that escapes from its frame: the relief formed by the pleated canvas in Nude Series VIII (1917), the watercolor technique which, by definition, extends beyond the forms which are predefined for it, and the jerky brushstrokes of Series I, No. 3 (1918) reveal that the painter’s techniques follow a movement of rapprochement and distancing similar to weaving, a pictorial phenomenon comparable to what Jacques Derrida calls the « stricture » in Truth in Painting (1978), this paradoxical contraction and dissemination of the work. Georgia O’Keeffe’s hypertrophic canvases therefore invite us to see beyond the boundaries fixed by the frame, thus responding to the principle of hypermodern excess.

Provided by the author

Other works like Pelvis (1943) seek to represent the unrepresentable, or nothingness, in a meta-artistic movement of mise en abyme of frames constituted by the gaps of bones within which meaning is briefly short-circuited to allow the feeling of operating. The spectator is no longer passive but active in front of the painting, a phenomenon thanks to which the work exceeds its contemplative function, echoing once once more the concept of hypermodern excess, and prefiguring ideas that will be developed much later, such as active participation of the public in the creation of the work of art.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (2020), Provided by the author

Georgia O’Keeffe, visionary artist

All in all, the Center Pompidou exhibition is the prologue to a hypermodern look at the work of Georgia O’Keeffe, a field of research as innovative as it is fertile. The works of the artist do not in fact correspond to the prerogatives of the modernism : Georgia O’Keeffe does not reject realism but exaggerates it by means of close-ups.

Her art therefore prefigures the symptoms of a crisis of modernity which marks the emergence of the hypermodern era: loss of identity, urgency and excess give rise to a hyperpolarised, hyperfocal and hypertrophic art which defines Georgia O’Keeffe as an artist. visionary.

His techniques continue to influence artists of the XXe and 21e centuries: by completely occupying the space of the canvas and by suggesting the cosmic immensity, his close-ups on details inspire maximalist artists such as Julian Schnabel while her audacity enthuses many feminists, including Mary Beth Edelson, a recently deceased contemporary artist. Georgia O’Keeffe was thus ahead of her time, and it is only today that it becomes possible to identify and theorize the full extent of her work.