The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, then the forced takeover of Credit Suisse by its rival UBS raised fears of a repeat of the 2008 banking crisis.

The essentials in a nutshell

- Whereas three years ago it was mainly equity volatility that activated “crisis mode”, today it is the expected fluctuations on the interest rate front that keep investors on their toes.

- The banking crisis will soon be forgotten and inflation will return to the center of attention

Almost three years have passed since the climax of the health crisis. Financial experts tend to coincide the March 2020 market low with the peak of the crisis. But regardless of the exact date, it is clear that this crisis is considered over. Obviously, the next crisis was not long in coming.

In less than two weeks, the bankruptcy of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, then the forced takeover of Credit Suisse by its rival UBS raised fears of a repeat of the 2008 banking crisis. Without even consulting the daily press, it would be possible to knowing with certainty, through the implied volatilities of options traded for different asset classes, whether the market anticipates an ordinary correction or a crisis. It should be noted that currently, it is more the volatility of interest rates that is raging than that of equities. Chart 1 shows, by way of example, the implied volatilities of equities, interest rates and currencies over the past twenty years.

Whereas three years ago it was mainly equity volatility that activated crisis mode, today it is expectations of interest rate fluctuations that keep investors on their toes. . Historically speaking, such volatility in rates corresponds to a VIX index of 50 to 60 and therefore to much greater stress in the equity market. However, the point here is not to evoke an alleged crash, but rather to focus on the subsequent evolution of interest rates. Obviously, the future strategy to fight once morest inflation and the management of the current banking crisis play a decisive role. After experiencing the fastest cycle of monetary tightening in decades last year in the wake of the restoration of monetary stability, in recent weeks we have witnessed a sharp fall in interest rates. High realized volatility logically led to high (implied) expected volatility. And now, what does the future hold for us?

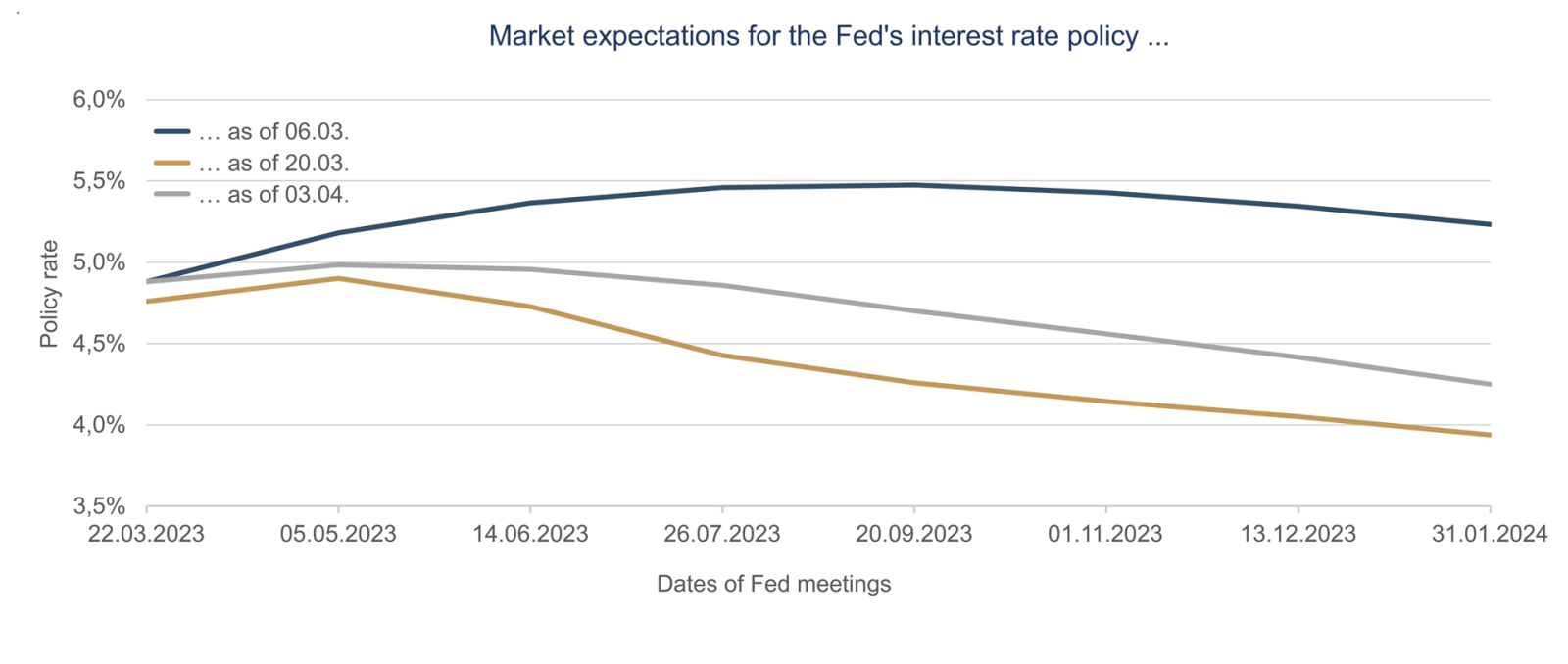

The current scenario is as follows: recent strains in the banking sector might help central banks fight inflation by tightening lending and credit conditions, especially for smaller banks. In other words: the tightening of financing conditions will partially offset the rate hikes needed to bring inflation back towards the Fed’s 2% target. Faced with tensions in the banking sector, markets expect the Fed to have less need to raise rates. Not because there would be no more inflation, but because the tightening of lending conditions will do all or part of it in its place. In this context, it is not surprising that investors’ expectations regarding the monetary policy of the Fed and the ECB have changed radically. Expectations reversed in record time, going from multiple rate hikes to multiple rate cuts. Chart 2 shows the Fed’s monetary policy expected by the market, in other words, priced in, on three different dates: March 6, 2023 (before the crisis), March 20, 2023 (announcement of the CS takeover) and currently (April 3, 2023). We clearly see a sudden disappearance of expectations of rate hikes from March 20. Expectations were then somewhat relativized.

In our assessment of the situation, however, we come to a completely different conclusion. The banking crisis will pass relatively quickly and attention will once once more turn to inflation. We believe that the consequences of the current crisis on the real economy are overstated. First, we must not forget that these are idiosyncratic risks that can lose their magnitude relatively quickly. Secondly, the measures taken by the Fed and the US Treasury to inject liquidity, calm the market and above all, restore confidence, seem sufficient to us. US officials have learned lessons from past crises and, in this case, acted hard and fast. Investor protection and liquidity injections have durably reduced the risk of a bank run and the likelihood of it becoming widespread. To reduce future burdens, the Fed also launched a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

In addition to the time-limited discount window, which allows the lending of a wide range of securities at a discount to market value, banks can obtain, through the BTFP, liquidity for one year at the face value of treasury bills, mortgages and agency loans. It is important that these facilities allow banks to build up liquidity in an orderly fashion, instead of frantically seeking funds or selling assets at a discount and realizing losses, which would only increase the likelihood of ‘subsequent hemorrhage of deposits. To assess the impact on the real economy, one must know the role of banks in the American credit system. It should be noted that the share of bank loans in private sector borrowing is relatively low.

Lending by small banks accounts for around 2% of GDP, compared to 3% for large banks, while the vast majority of credit comes from the financial market and other sources. In other words, the loans granted by the banks have only a minimal influence on the economy. If we look at the weekly bank balance sheet data, we also see that bank funding activity had started to slow last year, so well before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. The current crisis and the exodus of deposits from small banks to large institutions might further accelerate the decline in credit granted by small banks, but the growth of credit within large banks might partly offset this phenomenon. There is therefore no reason to say that the strains in the banking sector and their repercussions on financing activity will slow growth to an extent equivalent to one or more rate hikes.

On the other hand, what has not changed is the problem posed by inflation. The job market remains tight, the excess savings accumulated by households and businesses during the pandemic are still there, while income and spending growth seem to be stabilizing well above the level they inflation would have to settle at around 2%. These tensions still need to significantly ease. Until the current financial stress does not lead to a sharp slowdown in economic activity, it will be difficult for the Fed to move to a less restrictive course, let alone lower interest rates. If central banks manage to contain financial stability risks as expected, inflation risk might soon (and will) turn once morest them.