“May you be lucky” is the phrase that Olivia Zepeda hears most frequently while walking the streets of Yuma County, in the state of Arizona, right on the border with Mexico. She is the first Hispanic woman to launch her candidacy for the county Superintendent of Education position and luck is not exactly what she needs. What Zepeda needs is to mobilize a segment of Latino voters who traditionally vote poorly in midterm elections.

“If I can get Latinos in San Luis and Somerton to vote, I have a good chance of winning,” she says convinced at a support meeting where supporters and a small but effective army of voter promoters turned out, going from house to house inviting that people vote and that they know the candidate.

Olivia Zepeda prepares the campaign material that will be delivered during her tour through the streets of San Luis, Arizona.

(Alejandro Maciel)

Actually, Zepeda doesn’t need many introductions. Over 45 years she has exercised her vocation as a teacher in the classroom, and she has known first-hand generations of residents of that county. In a recent week in September in 95-degree temperatures with near 60 percent humidity, Zepeda is undaunted by the heat. Together with the promoters of her vote, she knocks on doors, she leaves information and talks with the neighbors.

“Your face looks familiar to me,” says a man who opens the door for him. “Didn’t you work at Rio Colorado Elementary School? I think you taught my daughter.” They both laugh and then Zepeda explains the importance of going to the polls next November. “Count on my vote,” she tells him.

But not only the classrooms is what Zepeda knows. For regarding 10 years of her career as an educator, she served outside the classroom as an associate county superintendent. There she learned regarding the administrative labyrinths of schools, budgets and the most pressing needs of teachers. But she also knew the problems faced by many of the 203,881 inhabitants of this county, where 65.5%, according to the 2020 Census, are Latino and the average family income is $48,790 per year.

“None of this is unknown to me,” says this 66-year-old woman, whose childhood was very similar to that of many of the children who study in this region, with a friendly smile.

Always forward

For someone who started working at the age of 4, necessity is the mother of all resources. Zepeda remembers the day his pride made him solve a serious problem. “I was 8 years old and the teacher mistreated me a lot and he told me that I had to bring a dictionary the next day or he would not let me enter the classroom. I asked my mom and she told me that she had no money, that she mightn’t buy the dictionary that cost 4 pesos”, Zepeda recalls and gets excited. “So I told my mom to help me sell popcorn. But we only had one peso. So my mom bought me 10 bags and made me popcorn. Sell them for 1 peso, she told me”.

To his surprise he sold them all, and from there began an activity that lasted a year. “My dad told me later that, during that time, thanks to the popcorn, the whole family got ahead,” he says with deep satisfaction.

That is perhaps one of the greatest talents that have been recognized in this woman from San Luis Rio Colorado and mother of 2 daughters: Her ability to find solutions when it seems that all roads are closed.

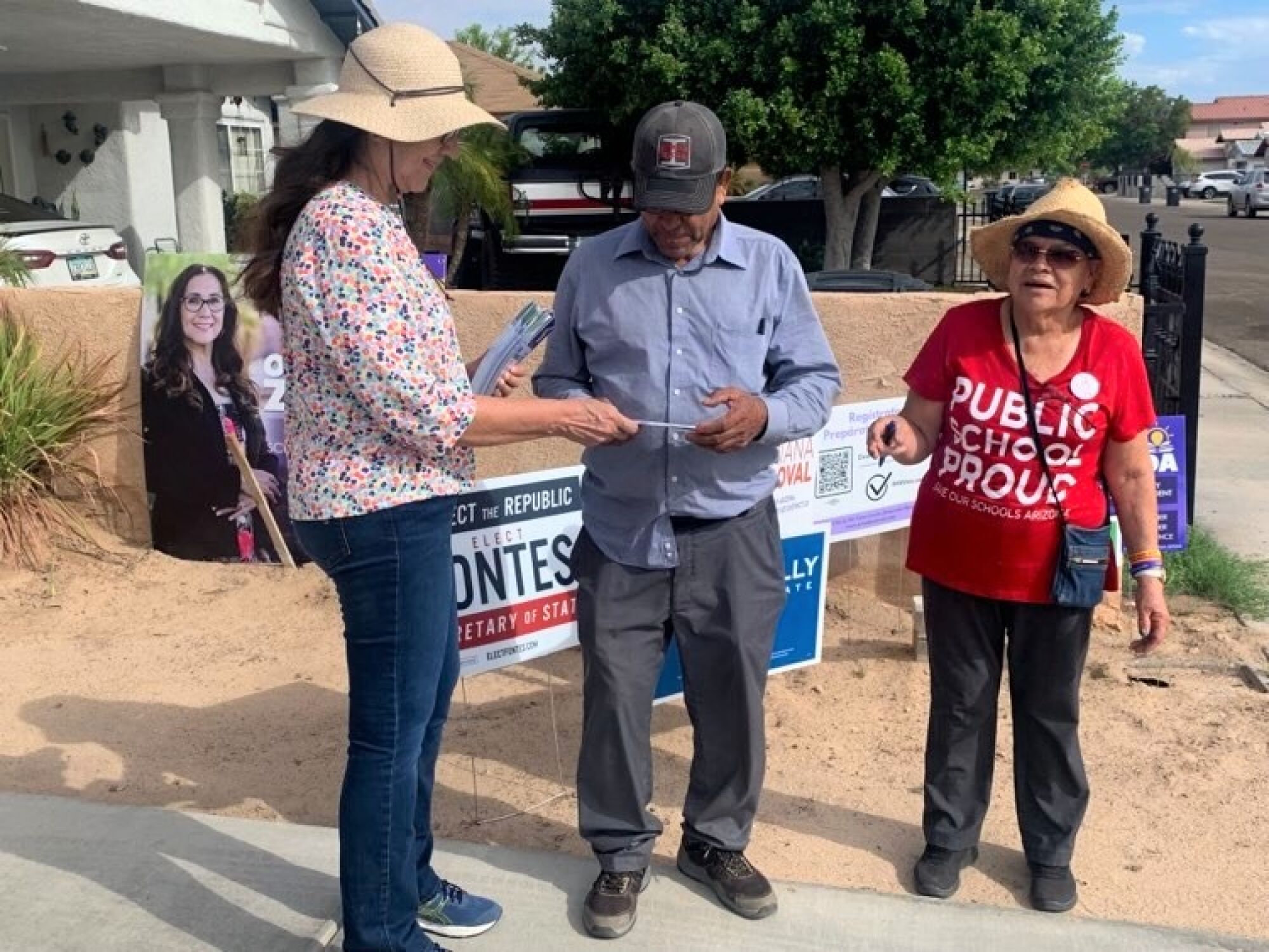

Olivia Zepeda and Juana Toledo talk with a resident of the city of San Luis.

(Alejandro Maciel)

As associate superintendent she was required to solve problems that the incumbent himself did not want to face. She has many stories from that time, such as when school cafeteria workers were willing to sue the District for mistreatment and abuse. “But the workers, as they knew me, wanted to talk to me and no one else… in the end I managed to find a solution and the district avoided a million-dollar lawsuit.”

“The Republicans pass by in their trucks, with the flags and they are following us and recording, they try to scare us, but they will not be able to. They are afraid of losing, but they don’t scare us.”

— Juana Toledo, volunteer promoter of the vote

But perhaps his toughest challenge was when a student died inside one of the schools due to a poorly anchored goal that fell on the boy and died. “It’s the worst thing I’ve ever experienced, because I know first-hand the suffering of parents and just like on many other occasions, I was the one in charge of dealing with things.”

In that moment of crisis, she showed what she was made of and why they trusted her. She mobilized resources, set up rooms to help parents, students, and teachers, called counselors, organized meetings, and managed to negotiate with parents who were enraged by what happened. “In the end I was able to tell them that, in their situation, I would be just as upset as they were, but it reassured them that the schools were safe and that they would do whatever it takes to improve student safety.”

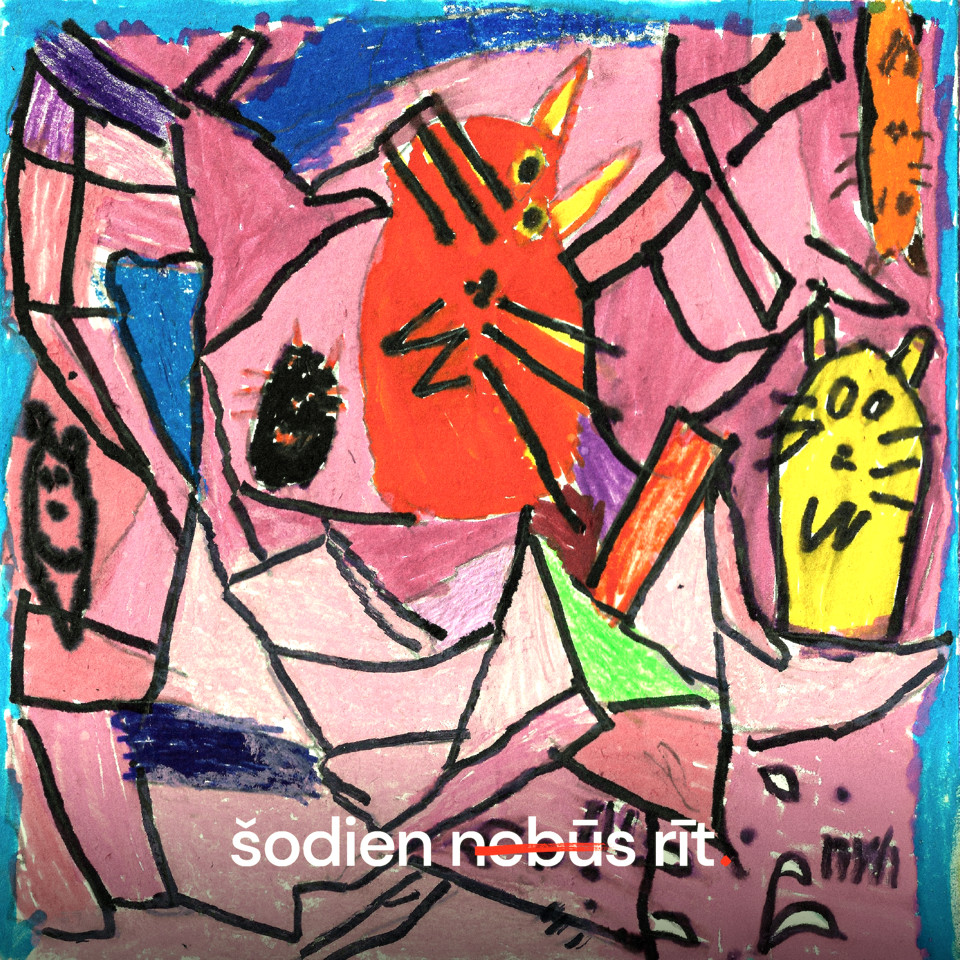

In the streets of Yuma County, Arizona, there is a great electoral ferment, where Latino candidates dominate the scene.

(Alejandro Maciel)

why did he never hold the position of county superintendent of schools, i ask?

“Because they always put obstacles in my way, and I preferred to retire from the superintendence to take charge of a school,” he answers.

But for a person like Zepeda, who is used to meeting challenges and overcoming herself, the idea of being a county school superintendent never quite went away.

“Yuma County has been my home for over 50 years. My experience is in curriculum development, instruction, budget management, human relations, and educational leadership. The qualities that I will bring to the county as a school superintendent will be consistency, dedication, reliability, and innovation,” she says with conviction. “I have prepared my whole life for this moment.”

forged in the field

Olivia Zepeda, (first from the right) in her teens, at work in California.

(Olivia Zepeda Archive)

Zepeda lives with her husband in Yuma. Her house is surrounded by extensive agricultural areas. While she drives her husband, she identifies the crops. “That one there is lettuce, those trees will soon be giving oranges and lemons.” Zepeda gets excited when she talks regarding the way dates are grown. “It is a machine that has a wheel that rotates in which several workers are placed who cut the dates that are already in the bags.” Her husband, Manuel Zepeda, nods.

Actually, she has always been surrounded by the farm fields. And when she has had a need, she has come back to them.

Manuel Zepeda repairs one of his wife Olivia’s posters.

(Alejandro Maciel)

“My dad was a bracero and we traveled with him following the crops. We would go near Modesto, California, and when we were lucky, we would sleep in a little house provided by the butler, but when we were unlucky, we would settle under the trees.”

From those difficult years comes an inner strength that is impossible not to see. Despite his sweet face, she has an energy and unwavering will to make things happen.

“I very much remember my mother who, despite the shortcomings and having nothing, never lost her optimism. I remember her accommodating the wooden house that they gave us in some fields. I remember her cooking, and the smells of the dishes that she prepared with all dedication for my dad, my sister and I to eat”.

And I say that she remembers the smells, because she lost her sense of smell at the age of 11, when one day, while working in the fig harvest in Planada, California, a small plane passed by and sprayed them with insecticide. “Since then I don’t have the sense of smell, but I have the memories of how things smell.”

“My dad told me later that, during that time, thanks to the popcorn, the whole family got ahead”

— Olivia Zepeda

For a migrant girl going back and forth between California and Arizona, the prospects for a formal education were slim to none, and what was expected of her was to finish high school and then go to work in a store. That was the aspiration of her father, who saw it as a way out of poverty and escaping grueling farm work.

But that was not in his plans.

Throughout his childhood, Zepeda remembers that every free day he had, holidays, weekends or vacations, he used to work with his father. “Those memories don’t hurt me, on the contrary, I value them a lot because I know that they shaped me into the strong woman I am now.”

And without a doubt for this electoral competition, he is going to need all his strength. His opponent, Republican Tom Hurt, won him by just over 3,000 votes in the primary election last August.

“There are not so many votes,” I tell him optimistically.

“Here there are a lot of votes, but that doesn’t stop me. We know that if we can get Latinos to vote, we can win.”

scare tactics

This is the “army” of voter promoters who support Olivia Zepeda’s campaign.

But convincing Latinos to vote is not his only challenge. In recent weeks, his army of voter promoters has felt the harassment of groups of Republicans who persecute them and record them with video cameras. “It scares me a lot, they are people who are very angry,” says Eloísa (she asked that her name not be used for security reasons). “They want people not to go out, not to vote, they want nothing to change,” she says as she adjusts her mask so that her face cannot be seen.

Juana Toledo is 77 years old. And since 1985 she has worked as a volunteer convincing people to register and go out to vote. “I know where the votes are,” she says as she walks heated down one of the streets of San Luis. “Yes, they persecute us, they record us, they say rude things to us, but they don’t stop us. What happens is that they are very afraid of losing, because they know that we can completely transform this county, ”she says as she hurriedly walks from one house to another.

Joining Zepeda is Zahid Templates, a 23-year-old running for the Gadsden School District Board of Directors. “We need to start taking political positions, moving forward from below, in order to solve the serious academic problems in our schools,” he says in impeccable Spanish and with a personality that demonstrates enormous political potential.

Tony Reyes, former mayor of San Luis, expressed his support for Olivia Zepeda and asked the promoters of the vote to continue their work. “You will be the ones to help change the political face of the county,” he said.

They and other candidates who support Zepeda are part of that new generation of young Latinos, who are convinced that it is time to participate and make things change in this county that during the election on August 2 voted 39.56. % in favor of the Republicans once morest 25.29% of the Democrats.

“It’s Olivia’s time,” says Tony Reyes, a former mayor of San Luis, Arizona. “She is a luxury of a candidate. I wish we had so many people like that to support.”