ive here. Richard Murphy describes how companies prefer dividends over employee wages as if that’s a bad thing!

Written by Richard Murphy, Chartered Accountant and Political Economist. The Guardian has described him as a “poverty activist and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University of London and Director of Tax Research in the UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Forum for Progressive Economics. Originally published in Tax Research UK

Having taken a quiet Friday followingnoon Posted this thread on Twitter This morning:

Conservative Party and Bank of England politicians constantly tell us that companies should not give employees wage increases that may be commensurate with inflation as this would create an inflationary spiral. But what regarding profits? Are they not the real cause of the problem? string…

The data I use on this topic has been researched by me with @adamleaver and others at the University of Sheffield School of Management and Queen Mary, London, and is available here. https://productivityinsightsnetwork.co.uk/app/uploads/2021/06/PIN-Report-29-6-21-FINAL.pdf

We looked at 182 companies that were consistently in the FTSE 100 from 2009 to 2019 to provide data for research. Some of these companies are among the biggest I’ve heard of. Others are somewhat smaller. The sample is wide.

The results were absolutely amazing. What we were looking for is:

- profitability

- Bonuses paid to shareholders

- employee costs

- Investments

- borrow

- What companies have you been investing in?

What was clear from the data was how strange that was. If 2009 is ignored as a crisis year, the value of these companies has grown by 54% in a decade, but sales have increased by only 21%, and value added has fallen by 18.6%.

What is also clear is that while employee salaries grew by 21%, earnings fell on average, but shareholder bonus payments such as dividends doubled with those at the end of the decade 218% higher than those at the beginning.

Notably, headcount at these companies has remained nearly stagnant over the decade and capital investment has risen by only 14%, with some variation on the way, with 2012 and 2013 being the best years ever.

But that is not all that is strange. We then divided these companies into five quintiles, which simply means we categorized them into groups of 36 or 37 companies each. We ranked them by the percentage of their net profit they paid to shareholders and got this data:

The 36 largest companies paid out 178% of their profits on average. The next 36 or so paid less: they only rewarded their shareholders with 88% of the earnings earned. Together, these companies represent 60% of the market capitalization of the companies surveyed and 56% of total sales.

As evidenced by the data, small businesses paid less than their dividends to their shareholders. On the other hand, its value was also lower.

However, looking at the data regarding how these companies actually behave suggests that it is difficult to justify these valuation differences. Take real sales growth, for example where real means we have removed the effect of inflation:

In fact, companies that overpaid in profits saw their real sales decline. The second group lags far behind the fourth and hardly outperforms the fifth group. Obviously, the value was not related to the ability to actually grow a company.

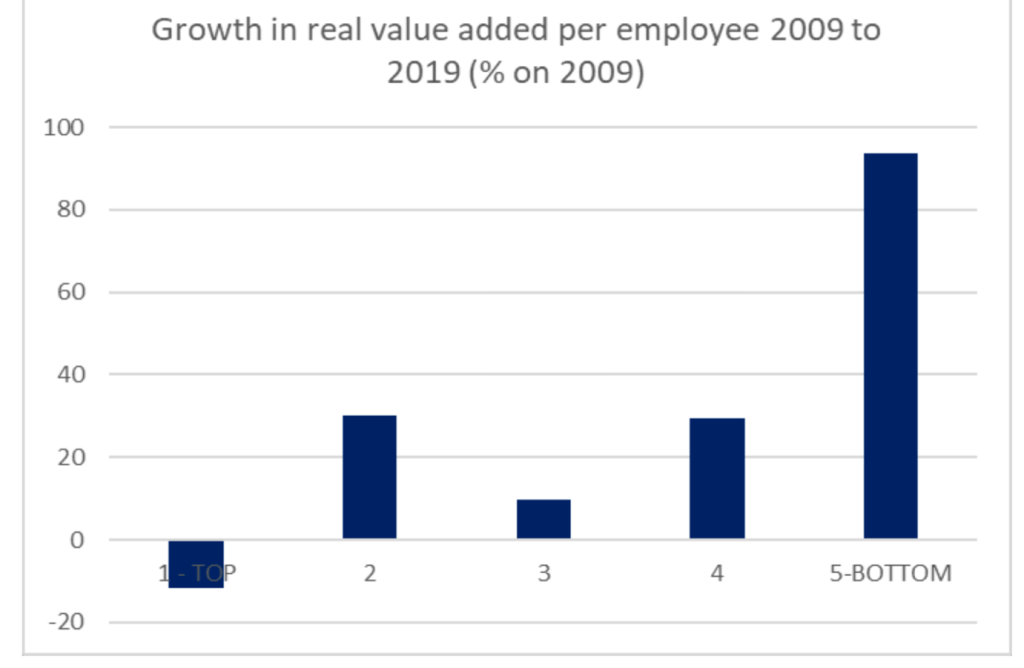

Then we looked at the real added value of each employee (i.e. once more, the rate of inflation). This may be seen as a measure of how much growth within a company is actually being generated by its skills and those of its employees.

Again, the first group did really poorly. In fact their performance declined. Companies paying less via dividends than dividends were the best, by far.

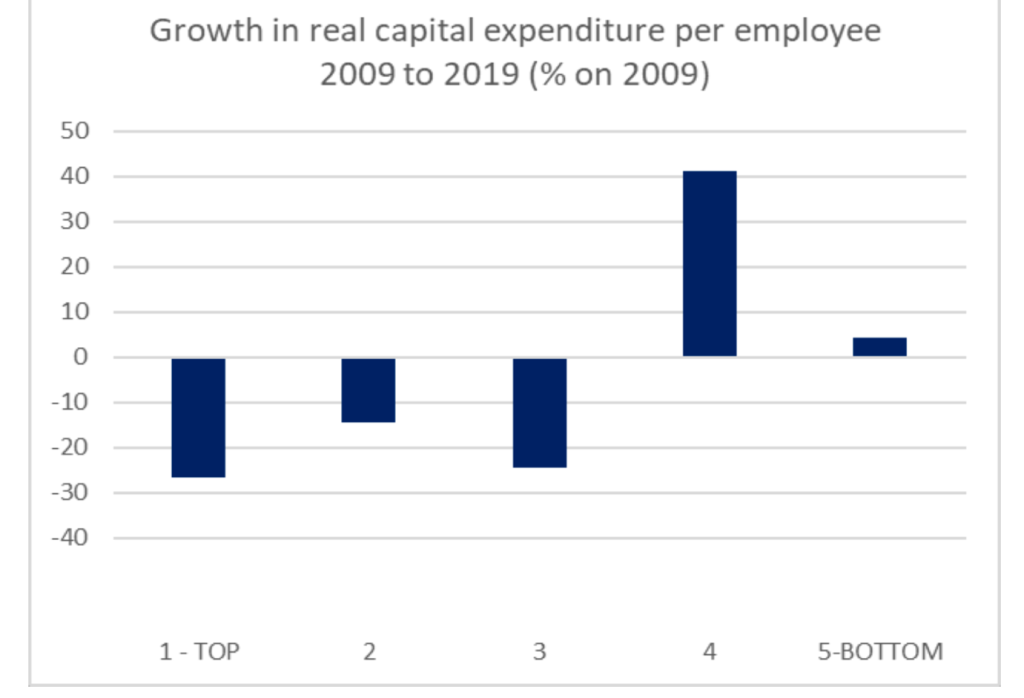

This may not be surprising: We then looked at each employee’s capital investment, with comparison by employee allowing us to consistently rank companies of whatever size:

Companies that paid less via dividends invested more in new capital equipment per employee. No wonder the real added value for each employee was even better.

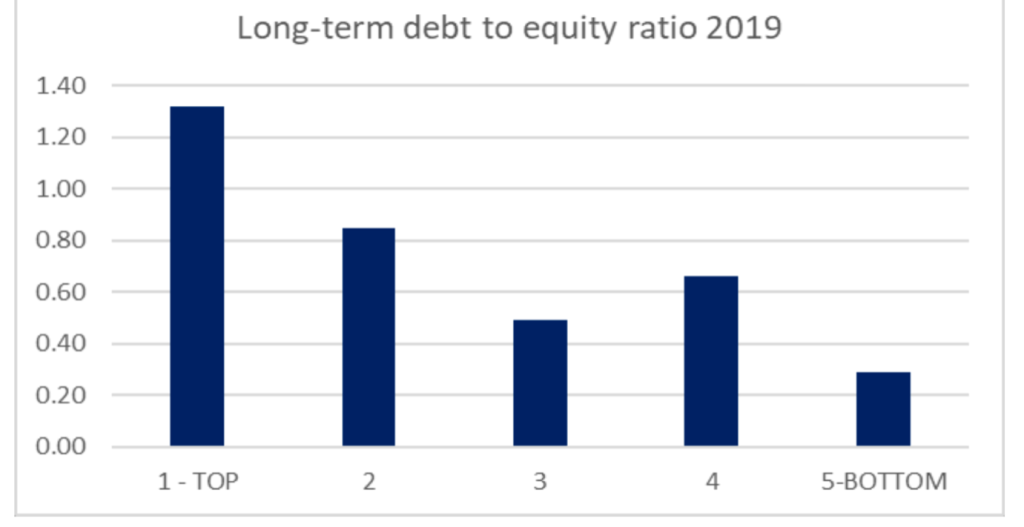

So, we then asked the obvious question, which is how do you manage these companies that pay more by way of dividends than they earn by way of profit? And they achieve it, of course, by borrowing much more than the average:

The less a company borrows and the more it relies on shareholder funds to support its activities (including dividends not paid out via dividends), the more it can withstand financial shocks, because it still has the ability to borrow when the unexpected happens.

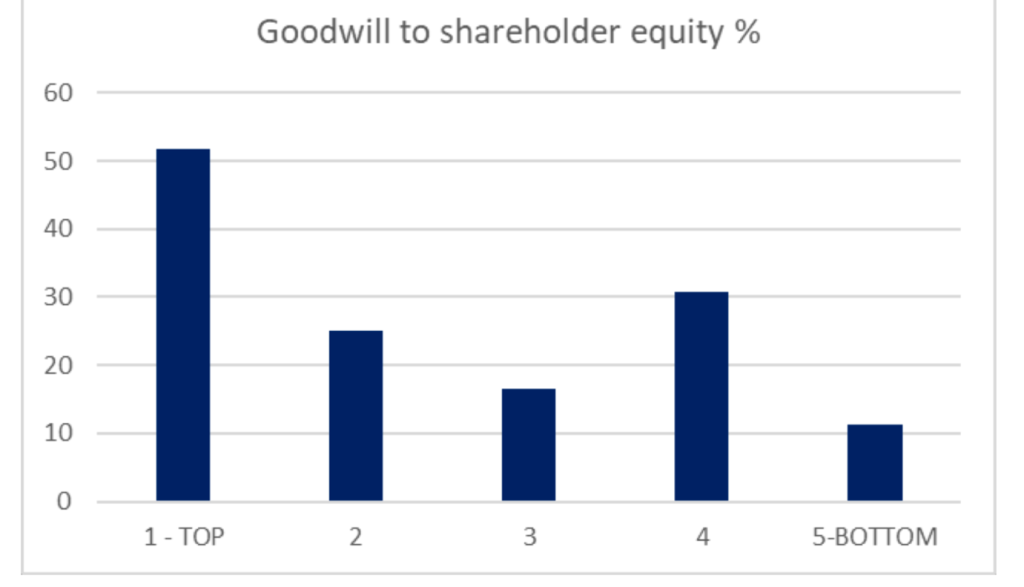

There was another big difference between the companies. Those who paid the most via dividends had the highest ratio of goodwill to shareholder funds on their balance sheets:

Goodwill is the amount paid to purchase another company in addition to the physical equipment purchased. Frankly, it is the price paid for the future profit that another company might make. Companies that pay high dividends are more willing to do this than companies that pay low dividends.

Perhaps this is because they know that they lack the ability to grow their own companies that those who pay less dividends seem to own.

I do not claim that this research answers all the questions that can be addressed in this topic. It is also definitely not investment advice. But it points to a number of really important things.

First of all, the majority by value of the FTSE 100 Index has, for over a decade, been paying nearly all of the profits made via dividends to shareholders, or much more than their own, which is staggering.

Second, these companies borrow money to pay these dividends. They seek to convert borrowing into dividend payments in relation to amounts earned to inflate stock market values, which seem to work with the companies doing so controlling the FTSE through valuation.

Third, this indicates that these companies care more regarding financial engineering than actually creating real value within their companies. How they might do this is suggested in a paper I co-authored here. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/media/28677/download?attachment

Fourth, as a result of these companies being invested, excluding the purchase of other companies, they may over-invest in them, creating risks for their shareholders and of course employees.

Fifthly, by looking at those firms that have decided not to pay nearly the same amount by way of dividends, we can see that the behavior of those firms paying excess dividends is a choice rather than a necessity. In other words, no law obliges them to act this way. Their recklessness is chosen.

But, and this is key, larger companies (in terms of value and sales) that focus on paying excess dividends as if their corporate purpose were creating real victims in the process. They achieve their results by suppressing wages and real investment, so we have poor salaries and productivity.

Companies that pay excessive dividends also increase their borrowing, putting their shareholders, employees, and the economy at risk.

By over-investing in buying other companies rather than creating real added value through their own capabilities, they are stressing their own budgets, and also encouraging an overvaluation of the FTSE as a whole, which is only a short-term gain.

Which brings me to another fundamental issue, which is why do the managements of these companies seek to exploit all those they deal with, lenders, shareholders and employees, by following these policies? There must be a reason.

Of course there is. Managing companies that screw up their companies to pay excess dividends do so to inflate those companies’ stock prices. Its directors’ bonuses are always correlated with increases in that share price. In this case their exploitation pays.

So, when companies (usually the largest companies) make the argument that they cannot pay wage increases that match inflation, what they are actually saying is that they want to continue paying dividends for inflation, often unearned instead.

The message is that these companies don’t want to pay inflation to match wage increases because they don’t care regarding employees, their company’s future, their sales, or keeping anyone as happy as possible by financial engineering that keeps turning loans into profits. .

Not every company is guilty of ongoing financial engineering. The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales is guilty of enabling it through guidance it issues on how dividends should be paid, allowing this breach to occur. And corporate greed is guilty of exploiting that advice.

But the fact is that if the biggest companies act responsibly and stop increasing their profits by making payments, they cannot justify paying the wages the UK economy needs to provide now to prevent many of their employees from falling into poverty.

If a business behaves responsibly in this way, it will also set the tone for all wage settlements. It is his choice not to do so. This choice must be challenged. Even shareholders are at risk of what happens. This behavior should end, now is the time to stop it.

Simple changes in the law can prevent this: Adam Leifer and I presented those rules to relevant government departments during discussions regarding audit reform, but major companies lobbied hard to maintain this status, and they seem to have won.

As a result, shareholder bonuses may continue to exceed their payroll, while increased inflation and hardship are likely, all to feed the greed of managers who seem to have reached the top of the company and see their money once. A lifetime opportunity to get rich quick.

Finally, I thank co-authors Adam Lever, Colin Haslam, Nick Tsitsianis and the University of Sheffield School of Management for enabling this work to be accomplished. The opinions here are all my own though.