- Somaya Nasr

- BBC News Arabic

24 minutes ago

picture released, Getty Images

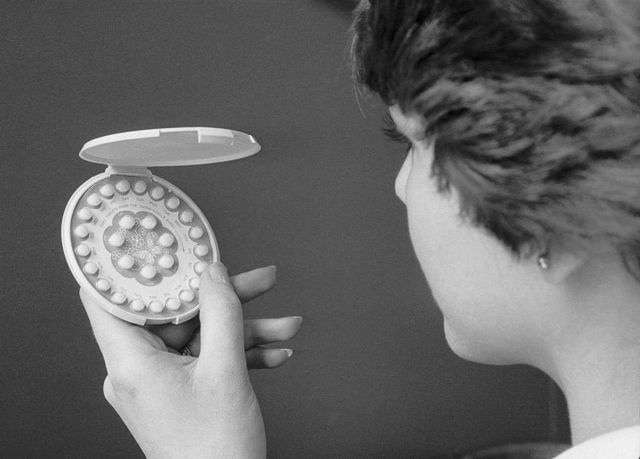

On May 9, 1960, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the commercial use of the world’s first birth control pills. These tablets have raised ethical controversy related to the experiments conducted on women, and many questions have been raised – and still are – regarding their safety and possible side effects of taking them. It was also welcomed for being considered to have contributed to the liberation of women, then derision for considering it one of the means of suppressing and controlling them.

safe way AndEasy to use

The American nurse Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) was the first to use the phrase “birth control” which means birth control or birth control. Sanger is considered one of the pioneers in the field of sex education and family planning, where she wrote many articles on the matter, and then opened the first birth control clinic in the United States in 1916, which led to her arrest and prison sentence.

Sanger was one of 11 children of a poor working-class family, whose mother had spontaneous abortions seven times. Margaret attributed her mother’s deteriorating health and death at the age of 50 to her inability to control her recurrent pregnancies. Perhaps this was one of the reasons why Margaret became interested in the field of birth control and sexual and reproductive health.

Through her work, Sanger has watched for decades how the fact that contraceptives are not available to a large segment of women has harmed the health of many of them, especially those who suffer from poverty and deprivation. She dreamed of a cheap and safe contraceptive that any woman in any part of the world might use easily.

A pill that a woman swallowed daily was an ideal alternative to the topical methods of the day, such as the diaphragm and spermicidal foam, which Sanger found to be too complicated for slum dwellers or the mentally handicapped. She hoped these pills would stop women from resorting to sterilization, separate sex from reproduction, and free women from the control of medicine and society.

picture released, Getty Images

Margaret Sanger has been arrested several times and sentenced to 30 days in prison for opening a birth control clinic and distributing pamphlets on contraceptives.

In the early 1950s, Sanger received a grant from her wealthy friend, women’s rights activist Katherine Dexter McCormick, to fund research into hormonal contraceptives. Sanger gave the grant to a research team led by experimental biologist Gregory Pinkas who was working in a Massachusetts lab, where he began developing a pill containing the synthetic hormone progestin, which mimics the hormone progesterone that a woman’s body produces following ovulation.

Pinkas hired gynecologist John Rock to perform a small clinical study on his non-pregnant patients to see if the pill would cause them to have a “false pregnancy.” Pinkas and Rock had to conduct their experiments in private, since distributing and researching contraceptives was still considered a crime under what were known as the Comstock Laws.

But the Food and Drug Administration would only approve the pills if large-scale clinical trials were conducted on women, so Roques and Pinkas had to overcome legal hurdles while meeting administration requirements.

Tell us your experience

Have you ever had an abortion for any reason? We want to hear your story.

If you’d like to share your story with us, use the form below to tell us briefly. We may contact you to prepare a story on the topic.

Privacy is reserved and your story may be published under a pseudonym.

perfect environment

The first large-scale trial of Enovid was conducted in 1956 in the US territory of Puerto Rico.

According to many medical history references, Puerto Rico was the perfect setting for such experiments, as it was one of the world’s most densely populated and poorest regions, and many women there desperately needed safe contraceptives, and they often resorted to sterilization. .

Participants were told that they would try a new, free drug that would prevent them from having children they might not support. Any married woman under the age of 40 who lived with her husband and who had at least two children was entitled to participate in the experiment.

Nearly 50 years following that experience, one of the participants, Delia Mistry, stated that she and hundreds of other women had not been told they were ‘lab rats’, or regarding the potential side effects of the ‘magic pill’.

In her book, “Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World,” Eleanor Cleghorn says that a report written by Dr. Idris Rice-Ray, director of the Family Planning Association of Puerto Rico who was responsible for conducting the trial, revealed that 17 in One hundred of the participants had side effects including nausea, dizziness, digestive problems, bleeding, vomiting and headache. But Pinkas and Rock, according to Cleghorn, downplayed these symptoms as the result of “excessive emotional activity” in Puerto Rican women. “They were only concerned with whether or not Inovid prevented pregnancy,” she adds.

“The experiences were good and bad at the same time,” Mistry says. “Why didn’t they let us make some decisions for ourselves?”

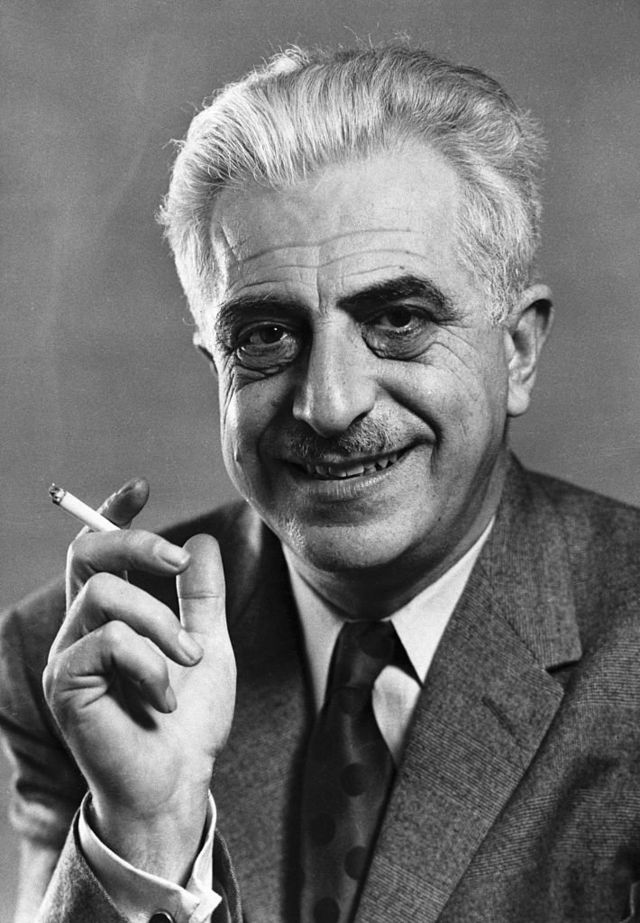

picture released, Getty Images

Gregory Pinkas

When Mestranol, a synthetic form similar to natural estrogen, was added to the ingredients in 1957, Inovid tablets contained three times the amount of progestin than today’s combined oral contraceptive pill.

Many historians have argued that experiments to test birth control pills on Puerto Rican women were motivated by a racist ideology of “eugenics,” or the study of birth control to “improve it” (which the Nazis later used to justify their treatment of Jews, the disabled, and other minorities), It was part of the historical exploitation of Latin American women to advance medicine and other fields in the United States.

“Racist fears of overpopulation have interfered with Puerto Rican women’s choices and reproductive freedom since the late 1930s, when contraceptives were allowed there, and laws were passed allowing sterilization of women…By 1970, regarding a third of Puerto Rican women had been sterilized,” says Cleghorn. Rico, and in many cases this happened without their knowledge or explicit consent.”

Side effects

By 1961, a year following the Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of Inovid, many concerns were raised regarding the safety of the “magic pill”, as there were many reports in medical journals of several side effects mainly around the occurrence of blood clots. In 1963, 30 women who took Enovid died.

The experiments continued in Puerto Rico until 1964, when Pinkas and his team members were working on the refinement and improvement of Inoved by testing it on women who urgently needed a method of contraception due to their difficult economic conditions, and so they tolerated the side effects of those tablets, which also included depression and various pains in the body. and decreased sexual desire.

In 1964, the company that produced Enovid had to include a warning leaflet in its packages that spoke of an “accidental occurrence” of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism”, but added that “a causal relationship has not been established between these health problems and the intake of Inovid”.

By the 1970s, there were reports linking birth control pills to fatal strokes, heart attacks, and blood clots, leading to a series of hearings in the US Congress.

picture released, Getty Images

The “magic pill” and women’s liberation

In the fifties of the last century, the pioneers of women’s liberation in the United States were opposed to the criminalization of contraception, as the number of women working for low wages in jobs such as teaching, nursing, secretarial and as factory workers was constantly increasing, and birth control was helping them postpone pregnancy until they finished their studies or prove their feet in the field of work.

And then those women welcomed the contraceptive pill, which they saw as an effective way to liberate women. Since it is women who bear the burden of pregnancy and childcare, feminists such as Margaret Sanger, Catherine McCormick, and others have argued that there should be a contraceptive method that the woman alone controls.

These pills also triggered what some call a “sexual revolution” for women, as they can have sex – whether within or outside marriage – without fear that it will lead to pregnancy.

However, congressional hearings in the 1970s drew attention to the potential dangers of the contraceptive pill, and feminists came to view it as yet another example of patriarchal control over women, and drug companies were accused of withholding information regarding the risks.

Women’s disillusionment with the “magic pill” has become part of the feminist criticism of American society, and women are beginning to ask: Why do men control the medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry? Why should birth control be a woman’s responsibility? Why is there no birth control pills for men?

picture released, Getty Images

Male contraceptive pills?

The last question is still asked and raises controversy to this day. The possibility of producing male contraceptive pills has been studied for decades. But researchers in this field are facing problems, including lack of funding, in addition to the complex process of inhibiting male fertility that targets the hormone testosterone, and, according to doctors, may cause weight gain, depression and raise cholesterol. A 1980 World Health Organization report on the acceptability of male contraceptive pills cited concerns that it might negatively affect a man’s “feelings” and “behaviour”, as well as his “libido”, something that most cultures consider highly valuable and part of men’s health in general. public.

Earlier this year, a team of researchers at the University of Minnesota announced the possibility of starting human trials on a non-hormonal contraceptive pill for men next July at the earliest, following its success in preventing pregnancy by 99 percent during its experiment on mice. One of those involved in creating the pills says they did not use any hormones in making them to avoid potential side effects.

More than sixty years following birth control pills were first used, and there have been four different generations, there is still a long list of potential side effects from taking them – some “mild” like dizziness, headache, vaginal discharge and mood swings, some serious like clots, high blood pressure and an increased risk of infection. Breast and cervical cancer when the tablets are used for a long time. Although the majority of doctors confirm that these serious symptoms are rare, and that the use of these tablets is still safe, there are those who demand more studies to reach a deeper understanding of their multiple effects, which vary from one woman to another.

From the beginning, the contraceptive pill was considered a way for a woman to control her body and her reproductive health. But it also meant, according to Eleanor Cleghorn, that “the cost — physical or mental — remains a woman’s burden alone. In a medical culture that turns a blind eye to and minimizes the health concerns women have regarding taking these pills, it is much easier to make a woman continue to bear these burdens.”

But with the announcement of promising male contraceptive pills, will men bear a greater share of the burden?