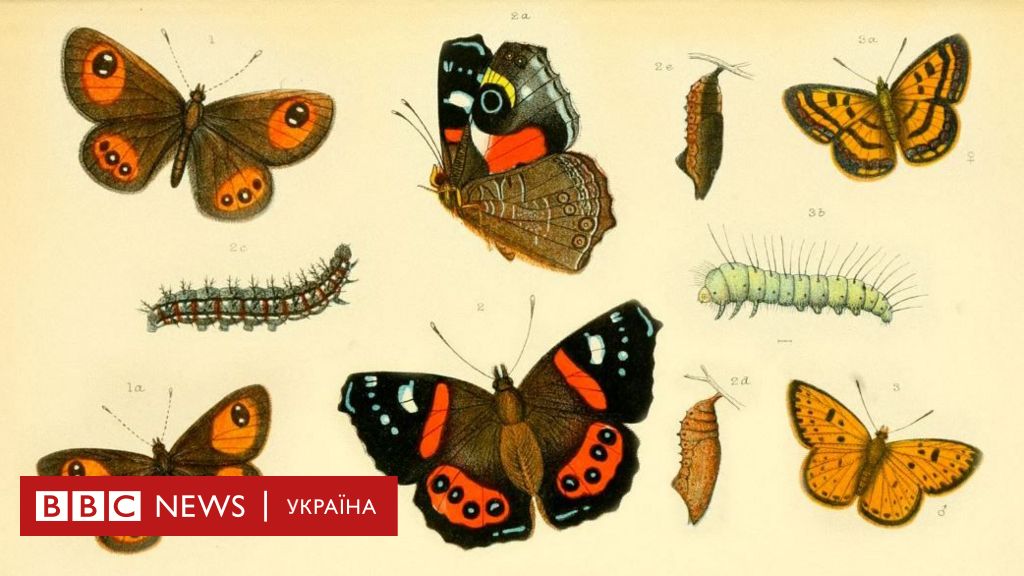

image copyrightInternet Archive and George Vernon Hudson

Article information

In the early 1880s, teenager George Hudson was enamored with insects. At the age of 13, the aspiring naturalist wrote his first manuscript regarding insects, which he collected and drew in detail. By the time of his death in 1946, he had written and illustrated seven books and amassed one of the largest collections of insect specimens in New Zealand.

But this commitment had its obstacles. When George started working at the post office, he faced a problem: there were more insects than he had time to hunt.

But Hudson was not one to let his passion get in the way, so he came up with a solution: turning the clocks back two hours during the summer months, a concept that became the prototype for the modern Daylight Savings Time system.

Such a change, he argued in addresses to the Philosophical Society of Wellington in 1895 and 1898, would allow the morning light to be used for work and the “long period of leisure” in the evening “for playing cricket, gardening, cycling, or any other pursuit outdoors”.

Apart from the savings in the use of artificial lighting, such a transfer would have been especially beneficial to the many people who were forced to work all day indoors, and who, under existing conditions, received a minimum of fresh air and sunlight, he suggested.

At first his proposal was met with derision and, although it received support in later years, it never went any further at the time. But Hudson was not the only person of his time to put forward such a proposal.

British construction worker William Willett noticed on his way to work in the morning that the shutters in the workers’ houses were mostly closed. Like Hudson, he reasoned that if the clocks were moved forward in the summer, people might start their day earlier and have more time to relax following work.

Photo credit: Alamy

Photo Caption,

George Vernon Hudson was fascinated by insects since childhood

Willett’s original proposal was to move the clocks forward 20 minutes every Sunday in April and back 20 minutes every Sunday in September, explains Emily Ackermans, curator at the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

In the end, his supporters settled on a one-hour transfer and first presented this proposal to Parliament in 1908. However, this measure was officially adopted by Germany only in 1916 – due to the need to save fuel during the war, and then, a few weeks later, by Britain.

This example was soon followed by numerous other countries, including the United States in 1918. And although Willet did not live to see the adoption of his initiative, because he died of influenza, Hudson witnessed how the corresponding law was passed in his native New Zealand.

However, until then, Hudson had to look for other options to find time for his passion. He would tailor his work shifts to use daylight hours to catch and paint bugs – and his passion for entomology only grew.

image copyrightInternet Archive and George Vernon Hudson

Photo Caption,

Uropetala carovei, or giant dragonfly, is one of many endemic species documented by George Hudson in his 1892 book

Follow us on social networks

Over nearly seven decades, he produced more than 3,100 paintings, as well as numerous books and extensive diaries of field research. It was his contribution to an era when “naturalists laid the scientific foundations of our knowledge of the unique nature,” writes Julia Kasper, lead curator of invertebrates at the Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand in Wellington.

Hudson’s system, where he recorded information regarding the specimens he collected in log books, each with a separate code, allowed him to record much more detail than the standard system, Casper notes. And because he collected the caterpillars and raised them to the adult moth stage, he was able to preserve them for painting much better than if he had caught the adults right away.

Several winged insects are named following him, including Mnesarchaea hudsoni, the small brown moth, and Pseudocoremia suavis, the forest moth.

image copyrightInternet Archive and George Vernon Hudson

Photo Caption,

Tree wētā is an endemic insect of New Zealand

Hudson collected a collection of several thousand insects, which is now housed in the Te Papa Museum.

This collection is not only extremely valuable for research purposes, but also documents New Zealand’s early insects in detail, Casper writes.

image copyrightInternet Archive and George Vernon Hudson

However, not all of the insects documented by Hudson exist today. The giant and mysterious insect mentioned in his 1928 paper – Titanomis sisyrota – may now be extinct, says David Lees, curator of insects at the Natural History Museum in London.

And while attitudes toward daylight saving time have been changing lately, Hudson, who helped bring it regarding, has left his mark on the passage of time – and reminded us that no one can stop it.