Slowly, livestock production in the province of Río Negro seeks to rebound not only in quality but also in the quantity of cattle, following a year that forced small producers to reduce expenses as a result of various factors, including the high cost of corn and food supplements.

The problem started with the high inflation rates that did not carry over directly to the price of meat. Quickly, those farmers who in previous years brought animals to the Alto Valle for “fattening” had to suspend that production link before the significant losses that was generating them and that they might notice day following day.

- 170.000

- are the animals that are slaughtered per year in the province of Río Negro. Most in Viedma, Roca and Valle Medio.

“The big problem last year was that the price of the fat (finished animal destined for slaughter) did not have the increase at the same time as the economy and inflation “explained the director of Livestock of Río Negro, Tabaré Bassi, when carrying out an evaluation of the situation in the provincial territory.

And he explained that for example, from July to December the price per kilo remained between 390 and 420 pesos per kilo, well below inflation rates which increased every month.

“It was six months where the price was practically ironed due to the problem of drought at the national level and there was a liquidation of stock. A lot of farm supply to fish”he expressed.

But there was a factor that had a strong impact on the accounts of the winners, not only from Río Negro but also from the rest of the country, which was the price of corn for food.

“The historical price in the port of Bahía Blanca was $175 a ton and last year it went to $250,” Bassi stressed.

- 640

- They are the pesos that are paid for the kilo of live animal meat. In January only 420 were paid.

The accounts did not give because the price of meat was maintained while food increased considerably.

If it is taken into account that a cow consumes 3% of its live weight (an animal weighs around 350 kilos), 9 kilos of food are needed per day, which left any producer far from the market value. To this we must add the price of the protein supplement per animal that is made from soybeans, sunflowers and we must also add some fiber and bale.

Basically an animal is maintained with 70% corn, 20% protein concentrate and 10% roll or bale.

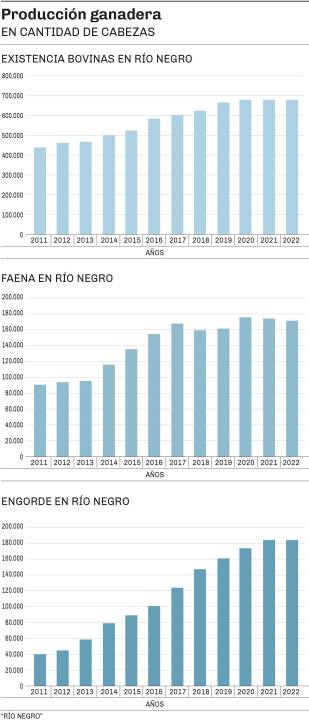

For Bassi, the reduction in the number of farms came to stop a growth in the heads of cattle in Río Negro that had been on the rise during the last decade.

“Ten years ago we had 40,000 head of cattle and today there are 180,000 for fattening. We grew more than 400% in recent years,” he explained.

And he explained that in Río Negro the total number of animals exceeds 700 thousand heads.

According to the official, the most direct consequences were faced by the smallest producer who does not have the financial support to overcome such an important economic gap and in such a short time.

“In the province we have many producers with less than 250 heads and they are the ones that suffered the most from the increase in corn,” he said.

And he remarked that those companies that produce their grass and corn and do not have to go out and buy it have managed to maintain the amount of property.

What happened was that that small producer did not close the numbers and ended up disconnecting from that link to only dedicate himself to breeding or reproduction.

Numbers were not closed to the small producer and he ended up disconnecting from that link to only dedicate himself to breeding or reproduction.

lag

Bassi stressed that this is a cyclical system and that for this reason already in the first months of 2023 fattening began to be activated once more due to the price of the live farm, which from 420 pesos per kilo in January and 475 in February went to cost 640 pesos in March.

“This means that fattening began to generate profitability once more, that is the good news for producers. The bad news is that the increase was transferred to the consumer”, summed up the reference from the Livestock area of the province, who was optimistic that this change will modify the livestock picture this year.

The work in Río Negro

For years regarding 170 thousand heads are slaughtered. 90% are slaughtered in three slaughterhouses: Fridevi, JJ Gómez and Luis Beltrán’s. Then there are others on a smaller scale in Jacobacci, Bariloche and El Bolsón.

75% of the fattened animals are slaughtered and consumed in the province of Río Negro, while the rest is transferred to other regions of Patagonia such as Neuquén and Chubut.

Sheep production does not pick up in the southern region

In the southern region of the province of Río Negro, the situation seems to be getting more complicated year following year, according to what the president of the Rural Society, Baldomero Bassi, pointed out yesterday.

The leader recalled that they have been facing a historic drought that began between 2006 and 2007.

“Then came the ashes from the volcano and now once more the drought that affects all the fields in the area located south of the Negro River,” he explained.

To this we must add the issue of pests such as pumas and red foxes that also affect small producers.

“To all this you have to add the value of wool in the market, which at one time was paid at 8 dollars a kilo and now is close to 4,” emphasized the leader.

all loads

The leader of the Sociedad Rural del Alto Valle pointed out that one of the biggest problems facing the producer -whether sheep or cattle- has to do with the tax burdens that are exerted.

“It happens with soybeans and with all those exportable raw materials. It happens with wool and meat,” said Bassi, who clarified that the situation is really complex because many of these people raise small numbers of animals.

In Río Negro, 85% of the wool producers have more than 1,500 sheep and then there are the others who have less than 500 and have sheep for subsistence.

“To all this add that we have the doubling of the dollar. All this complicates the business and makes many people emigrate from the countryside to the big cities.

“The situation tends to mean that many young people do not want to be in rural areas anymore and today they only find older people. It is difficult to continue with the productive activity ”, he pointed out.

A subsidy of 600 pesos per sheep

In March of this year, the national government began to pay the Plan Lanar subsidy, which provided a contribution of 600 pesos for each sheep to producers in Patagonia.

This is the Economic Compensation Program for Small and Medium Sheep Wool Producers in the Patagonian Region, which was announced in November 2022. For the president of the Rural Society, it is a contribution that does not help producers much, although he explained that they are waiting for another subsidy to strengthen the sheep sector in Patagonia.

To comment on this note you must have your digital access.

Subscribe to add your opinion!

Subscribe

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25626687/DSC08433.jpg)