Ultra-Processed Foods: Election Impact & Health Crisis

U.S. ports and Air Freight See Sharp Cargo Drop Amid Tariff Fears WASHINGTON – Major U.S. ports and air freight companies are reporting a significant

U.S. ports and Air Freight See Sharp Cargo Drop Amid Tariff Fears WASHINGTON – Major U.S. ports and air freight companies are reporting a significant

Arsenal Aims for Champions League Glory, Set-Piece Prowess Key Against PSG April 29, 2025 Arsenal is set to face Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) in the Champions

Capitals Dominate Canadiens in Game 4, Poised to Advance By Archyde News Service April 29, 2024 MONTREAL — Andrew Mangiapane broke a 2-2 tie with

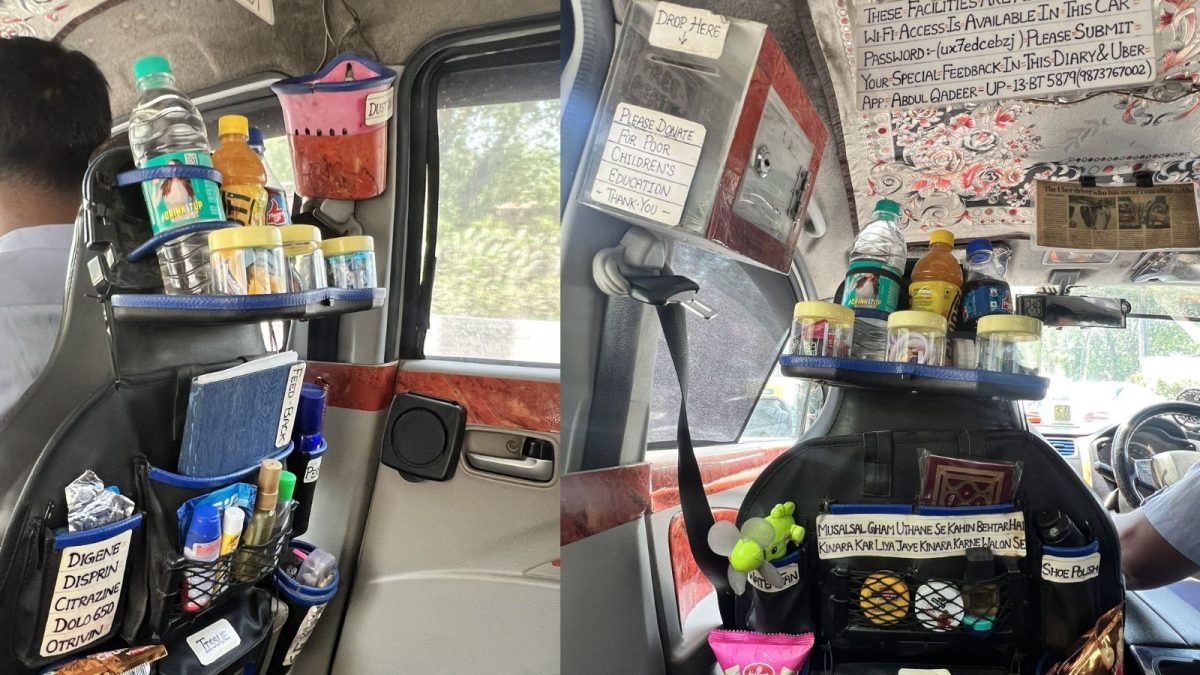

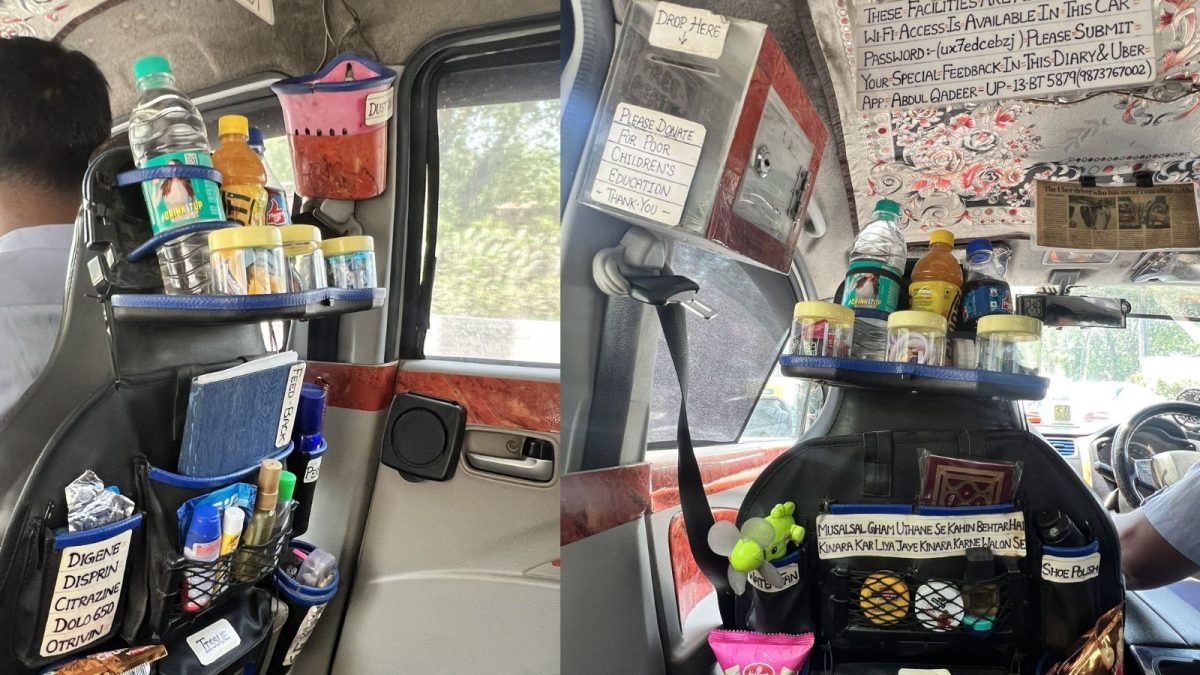

Uber Driver’s ‘1BHK’ Car Goes Viral for Amazing amenities By Archyde News Service April 28, 2025 in a world saturated with ride-sharing stories ranging from

U.S. ports and Air Freight See Sharp Cargo Drop Amid Tariff Fears WASHINGTON – Major U.S. ports and air freight companies are reporting a significant

Arsenal Aims for Champions League Glory, Set-Piece Prowess Key Against PSG April 29, 2025 Arsenal is set to face Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) in the Champions

Capitals Dominate Canadiens in Game 4, Poised to Advance By Archyde News Service April 29, 2024 MONTREAL — Andrew Mangiapane broke a 2-2 tie with

Uber Driver’s ‘1BHK’ Car Goes Viral for Amazing amenities By Archyde News Service April 28, 2025 in a world saturated with ride-sharing stories ranging from

© 2025 All rights reserved