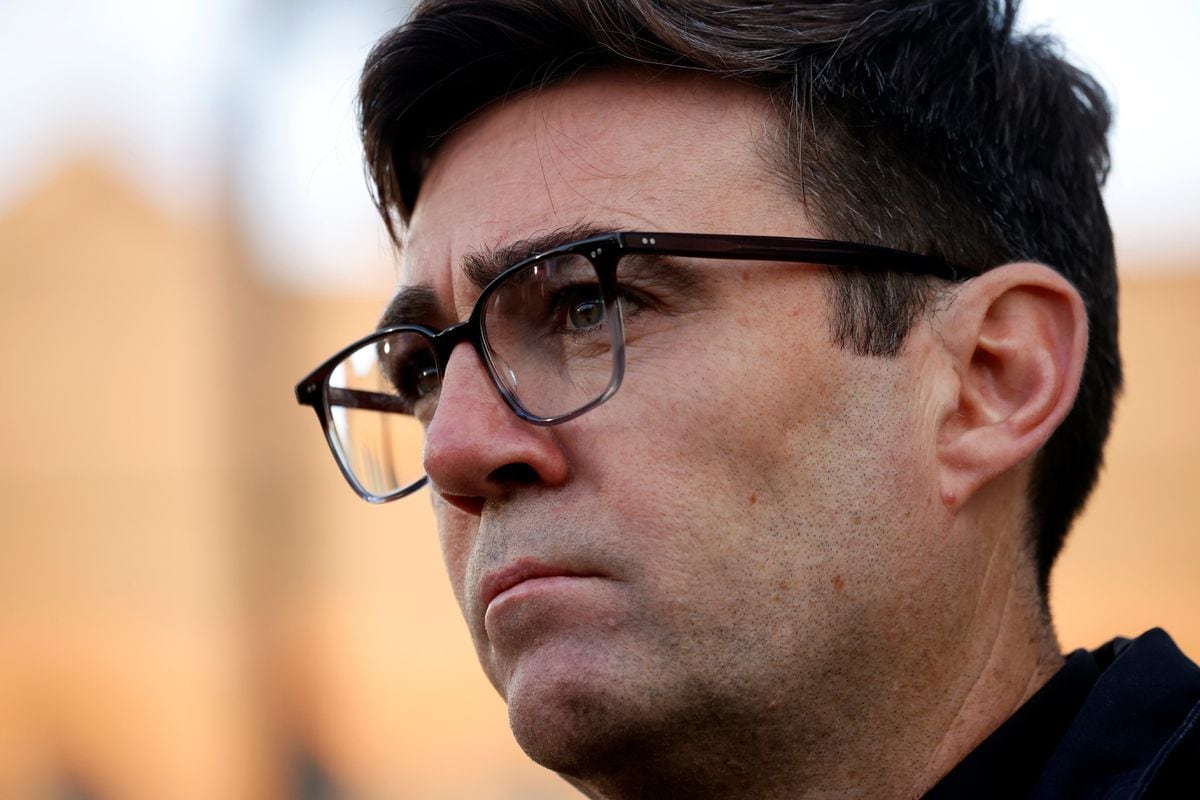

Andy Burnham (Liverpool, 54 years old) does not dress like a mayor. Black pants and T-shirt, black blazer, he has the elegance of a mature British alternative rock star from the late eighties. He might be the fifth member of his beloved The Smiths. The Labor politician is in charge of a city – Manchester, where that band emerged – but above all of a region in which almost three million souls live –Greater Manchester— which will be fundamental in determining whether the leader of the opposition, Keir Starmer, has been able to regain the support of the north of England, with a strong leftist tradition, but which switched to the Conservative Party and Boris Johnson’s Brexit in 2019. The called “red wall”, whose bricks crumbled. The city, along with its neighbor and rival Liverpool, symbolizes the resurgence of a northern pride.

Nothing is more liberating than municipal politics. Burnham laughs and does not hesitate to show his tattoo on the bicep of her right arm: a small bee, the symbol of an industrial and industrious city like Manchester. Hundreds of Mancunians, as its inhabitants are known, engraved it on their bodies as an emblem of pride, solidarity and resurrection that they all shared when the American singer Ariana Grande returned in 2019, to perform once more, two years following that tragic terrorist attack. in the Manchester Arena stadium that killed 22 people, many of them minors.

“No tattoos, no cigarettes, no motorcycles. Those were my mother’s sacred laws. And I’ve skipped them all,” laughs Burnham. The son of a telephone line technician and a receptionist, it was the “Battle of Orgreave”, that brutal confrontation between miners and police in 1984 that historian Tristram Hunt described as “almost medieval in its choreography”, that galvanized young Andy , aged 14, to join the Labor Party.

He was an MP for 16 years, and a minister in the governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. Long enough to understand that British national politics, focused to a fault in London and that bubble of deputies and advisors colloquially known as Westminster, causes a numbing of conscience. “The more time you spend there, the more you look like a fraud to the citizens. Because you vote for things you only half believe in. You end up partly losing the sense of your own personality,” he explains.

Football and regional pride

To understand Burnham’s definitive leap into municipal politics, another tragedy must be introduced into the narrative: Hillsborough Stadium, Sheffield. 1989. FA Cup semi-finals (the tournament similar to the Copa del Rey in Spain). Liverpool FC once morest Nottingham Forest. 97 dead and almost 800 injured when the standing bleachers collapsed. And the general conclusion, fed for almost two decades by the British political class, that what had happened had been the consequence of the savagery of the hooligans, of the northern barbarians. “Following the findings of the second public inquiry into the incident, I said in the House of Commons – his 11-minute speech takes pride of place on Liverpool FC’s YouTube channel – how is it possible that the entire “An English city will demand justice in tears for 20 years and Parliament will not listen?” Burnham recalls.

The mayor gained national prominence during the pandemic, and earned the nickname “king of the north” when he faced Boris Johnson’s government. He fought – unsuccessfully, but with popular support – once morest draconian confinement measures in the region, different from those in London and without the financial support necessary to resist them.

That battle helped many Labor members understand that the response to the conservatives was in the municipal trenches. The disenchanted electorate might be won back with investments in infrastructure, aid for education, cultural proposals and an injection of pride for an England that had been feeling abandoned for years.

There it is, Burnham defends, the reason for a support for Brexit that surprised the leadership of her party. He remembers how hard it was for him to defend remaining in the EU among his voters, and he understands that Keir Starmer does not want to stir that issue now. “Reentry is not a political option that is on the table right now. But I trust that the next generations, our grandchildren, will bring the United Kingdom back into the European Union,” says the mayor.

Burnham has twice stood for the leadership of the Labor Party. Today he is a fundamental ally of Starmer, but he will never stop being an annoying shadow for the current candidate. First of all, because he does not rule out his return to the national scene. Secondly, because his charisma among voters is undeniable.

But today, with a network of Labor mayors making use of their recovered powers, he believes that, if the polls do not fail and the left conquers Downing Street – he anticipates that the elections will be in November – the leader of the opposition will have it. easier than Tony Blair in 1997. “Then we came to power with immense popular support, very high expectations and no ability to transfer our policies to the regions. Starmer will arrive with low expectations and a very different regional infrastructure. The honeymoon will be brief, because people are impatient, but the new Government will have much more capacity to act immediately,” says Burnham.

Follow all the international information on Facebook y Xor our weekly newsletter.

to continue reading

_