Galactic Methuselahs: Astronomers have uncovered our galaxy’s oldest population of stars — the metal-poor, ancient heart of the Milky Way. These stars are almost 13 billion years old and formed before the star disk of our galaxy. The oldest part of this population in the galactic center includes around 18,000 stars and at least 50 million solar masses, as the researchers determined. These galactic Methuselahs are far more numerous than assumed.

Our Milky Way has a long, eventful history behind it: After its formation a good 13 billion years ago, its star disk and halo gradually formed. In your “Teenagerzeit‘ our galaxy then grew through mergers with dwarf galaxies and collisions closer and got before around ten billion years its central bulge and its current shape.

Manhunt in the heart of our galaxy

But how many of the oldest, most primordial stars in our galaxy are still preserved today? And when and where did they arise? According to current assumptions, such ancient relics of the proto-Milky Way are most likely to be found in the galactic center. In fact, astronomers have already discovered some extremely metal-poor stars there. These contain almost only hydrogen and helium and must therefore have originated in a primordial environment that has hardly been enriched with heavier elements by supernovae.

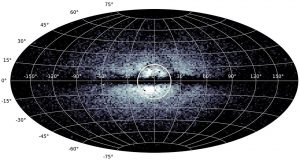

In order to find out more regarding this first population of stars in the Milky Way, astronomers led by Hans-Walter Rix from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg have once once more searched for old metal-poor stars in the center of our galaxy. To do this, they evaluated the data from the European Gaia satellite on more than two million giant stars in the vicinity of the galactic center using an adaptive neural network.

Surprisingly many Methuselah stars

The analyzes revealed: In the center of our galaxy there is indeed a whole population of ancient, metal-poor stars. Around 100,000 of these stars therefore have significantly less heavy elements than the oldest parts of the galactic star disk. “This is an order of magnitude more of such objects than determined in previous surveys of the inner galaxy,” the astronomers state. These metal-poor old stars are concentrated in an area regarding 15,000 light-years from the galactic center.

Around 18,000 of these old stars even have a ratio of metals to hydrogen of less than minus 1.5 – they are therefore particularly old and original. These central metal-poor stars existed before the oldest stars in the galactic disk, which are around 12.5 billion years old,” report Rix and his colleagues. These central ancient stars might therefore have belonged to the basic building blocks of the young Milky Way.

Altogether, these ancient stars have at least 50 million solar masses, but it is likely more than 100 million solar masses, as determined by Rix and his colleagues.

Formed as early as the proto-Milky Way

With this, astronomers have for the first time tracked down the ancient heart of the Milky Way – the stellar population that existed from the very beginning of our galaxy. The analyzes indicate that some of these ancient stars are likely stolen: they came from the similarly old cores of neighboring dwarf galaxies that were once swallowed up by the Milky Way.

But most of the metal-poor Methuselah must have formed locally—at the center of the proto-Milky Way. “These stars once formed the tightly bound part of a proto-galactic sphere,” the team said. Evidence of this includes the narrow, nearly circular orbits of these stars and a composition that suggests rapid formation in a high-gravity environment.

“Poor old heart” of our galaxy

“Our results do not represent a completely new, previously unrecognized stellar component of the Milky Way,” the astronomers emphasize. But the now-identified stellar population proves that the previously known individual detections of old stars represent only the tip of an entire iceberg of pristine stars from the early Galactic period. For the first time, the new analyzes provide a more complete picture of the “poor old heart” of the Milky Way. (The Astrophysical Journal, 2022; doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac9e01)

Source: Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

December 21, 2022

– Nadja Podbregar