The Spanish right has always been reluctant to amnesties. In the middle of the transition, in 1977, Alianza Popular, precursor of the PP, abstained from voting on the law. For Antonio Carro, Franco’s former minister and elected deputy of the party led by Manuel Fraga, removing prisoners from prisons represented a kind of “taking of the Bastille.” “They assumed that the Francoist State was governed by law and the amnesty called that into question,” explains Carme Molinero, historian and author of an extensive bibliography of the period of the dictatorship. “A responsible democracy cannot continually amnesty its own destroyers,” stated Carro from the speakers’ gallery. The law passed with 296 votes in favor, two once morest and 18 abstentions, a broad consensus that is precisely what the Venice Commission lacks in the current project agreed between the Government of Pedro Sánchez and the Catalan independence parties. If the predictions do not fail, this amnesty will be approved by 178 votes in favor and 172 once morest.

“That 1977 amnesty had no constitutional framework to obey and was a parliamentary initiative, not a government initiative like the current one,” says Ricard Vinyes, historian, former commissioner of Memory Programs of the Barcelona City Council, former president of the drafting committee of the Memory Institute of the Basque Country and member of the commission on the Valley of the Fallen. “During the Transition there was a very important cultural dimension between part of the right and the entire left that pointed to the need for change,” adds Vinyes. “It was, as Manuel Vázquez Montalbán said, a sum of weaknesses to build a complete democracy,” says Molinero. That political culture now seems completely buried.

The amnesty law of 1977 was preceded by two decrees—1975 and 1976—that pardoned political prisoners without blood crimes. “As paradoxical as it may be, the 1977 amnesty has no prologue, compared to the 1976 pardons, which do have an excellent introduction,” says Vinyes. Europe is a land with a long tradition of amnesties, emphasizes the historian, who cites the Edict of Nantes (1598) as an example, since it prohibited the memory of what happened during the religious wars. It was signed by Henry IV, who changed from Huguenot to Catholic during the conflicts. “Amnesties have something of forgetfulness and something of a full stop law,” says the expert in matters of historical memory. In fact, the 1977 victory, although considered a victory for the left, in practice also shielded “the crimes and misdemeanors that the authorities, officials and agents of public order may have committed as a result of or on the occasion of the investigation and persecution of the acts included in this law”, as stated in the second article. Therefore, it also favored the right.

That blank slate has always weighed on Spanish politics. In 1986 the PSOE wanted to structure a pact of oblivion on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the start of the Civil War, Molinero recalls. But the fall of the military dictatorships in Chile and Argentina reopened the debate on historical memory in a country in which the right has avoided explicitly condemning Franco’s regime, adds the historian.

In fact, the 1977 amnesty, approved during the constituent period, imprisoned barely a hundred prisoners, most of them related to blood crimes and basically members of the FRAP or anarchists. The Government of Adolfo Suárez had negotiated with ETA the expulsion – sending to third countries, mainly Belgium – of the vast majority of the organization’s prisoners. This measure was intended to avoid the high abstention that was expected for the elections of June 15, 1977 in the Basque Country.

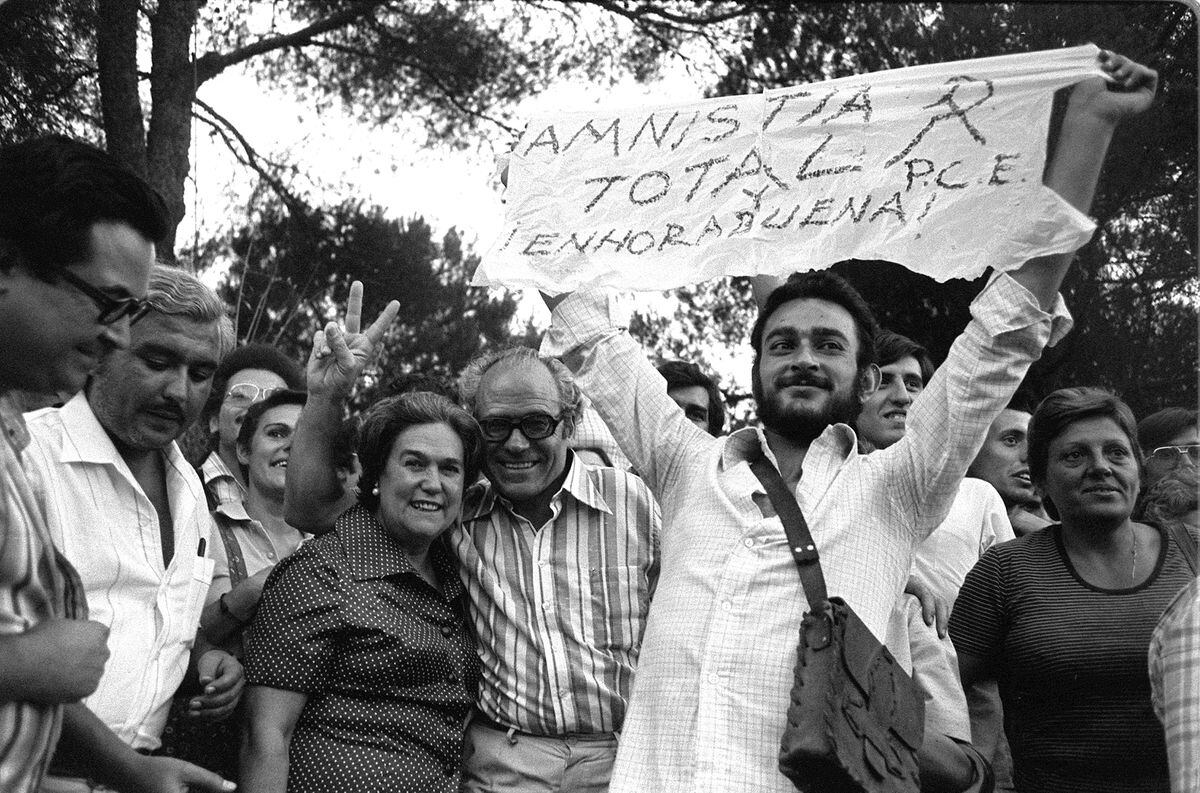

They were turbulent years, far from the image of a model and orderly transition. If the last executions of the Franco regime of five members of ETA and the FRAP were on September 27, 1975 —when the dictator was dying—, following two major pardons, on January 24, 1977, the murders of the labor lawyers of Atocha took place. . Nor should we forget the violent repression of pro-amnesty demonstrations throughout Spain and especially in Euskadi, where in 1977 the police killed seven people in one week.

What affects the most is what happens closest. So you don’t miss anything, subscribe.

The application of amnesties and pardons is not always easy. It has its complexities. Carles Vallejo, president of the Catalan Association of Former Political Prisoners of Franco’s regime, remembers the adventure he experienced in the mid-eighties at the police station: “I went to report the attempted theft of my car, whose window had been broken; and upon arriving at the police station I was detained for six hours until the situation was clarified.” “The reason was a search and arrest warrant that was still in my file,” he recalls.

Vallejo had been arrested for the first time in December 1970, during the campaign once morest the Burgos War Council, in which members of ETA who had ended the life of Commissioner Melitón Manzanas, known for his brutal interrogations, were being tried. At the Barcelona Police Headquarters he was tortured for 20 days. In 1971 he was arrested once more for participating in the clandestine organization of CC OO that led the union struggle in the Seat factory in the Barcelona Free Trade Zone. After the new arrest, he escaped to France while awaiting trial. He was declared a fugitive and in Italy he obtained refugee status. He returned to Spain in 1976, as he was pardoned like Marcelino Camacho when the King relieved Franco as head of State, at the end of 1975.

“The difference between the 1977 amnesty and the one now is that that was to move from dictatorship to democracy and the current one allows for the restoration of the climate of coexistence in Catalonia,” says Vallejo, very concerned regarding the conservative visions of justice that They associate the protest of social movements with terrorism.

to continue reading

_