‘Spring Uninvited’ Yellow dust has plagued us several times this year in winter as well. It was observed four times in January this year alone, and it is the highest since weather observation began in 1960.

Yellow dust refers to a phenomenon in which sandy soil blown up by the wind falls to the ground like rain. Where did this sandy soil from Korea come from?

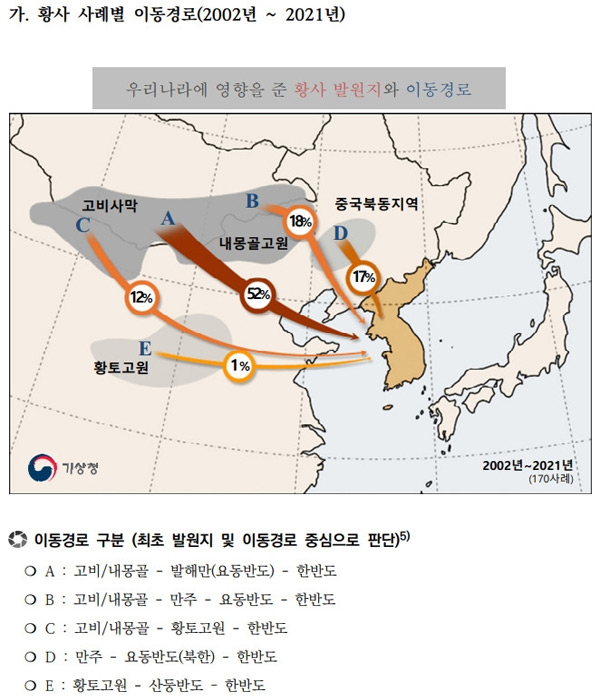

Yellow dust source statistics [자료제공 : 기상청]

This is a data showing the origin and movement route of 170 yellow dust that fell in Korea over the past 20 years. More than half of them originate from the Gobi and Inner Mongolia regions, which correspond to Mongolia and northern China, and pass through the Bohai Sea.

In particular, the Korea Meteorological Administration explains that since 2000, yellow dust from Mongolia has occurred more frequently than yellow dust from China.

Why is the yellow dust blowing from Mongolia increasing? In December of last year, on the day yellow dust covered the country, the National Institute of Environmental Research under the Ministry of Environment came up with this analysis.

“Sandstorms are occurring more frequently as the average annual temperature rises in Mongolia and northern China, the source of yellow dust.”

As the temperature rises, the source of the yellow dust turns into a more barren land, creating conditions for sandy soil to blow more often. Even in winter, the dry land is not covered with snow, and the frequency of yellow dust in winter is increasing.

In other words, climate change is having a big impact on the yellow dust coming into Korea from Mongolia.

Cattle move north in search of grass in a grassland in Dondgobi, central Mongolia.

We headed to Mongolia to cover what was happening in the yellow dust source.

It took three and a half hours from Incheon Airport to Mongolia’s Genghis Khan International Airport. As soon as I got out of the gate, I found a thick padding and put it on. The temperature in Ulaanbaatar that day was minus 15 degrees Celsius. In addition to this, the wind blowing at 40 meters per second, which said that the train might derail, made my whole body freeze at any moment.

Even the pain of the cold for a while. Shortly following driving to Southern Mongolia, the expansive Mongolian scenery quickly catches your eye.

The horizon meets the sky. Sheep and goats graze on the vast expanse of land. Nomads on horseback followed.

However, the scenery that looked beautiful from afar was different when I looked closer.

The El Seung Tasar Sea Desert arrived in four hours by car west from Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia.

Endless stretches of sand dunes undulate. A desolate land where it is difficult to grow even a single blade of grass to feed livestock. This is the 80-kilometer-long El Seung Tasar Sea desert area.

Elseungtasar Sea in Mongolian means ‘broken sand’. This is because desert areas are not connected to each other, and vegetation is growing in between.

However, the places where sheep and horses used to graze are gradually disappearing, and the desert is expanding at an alarming rate.

Mr. Baddurji, a nomadic herder, tends livestock in the grasslands near the Elseungtasar Sea Desert.

It is less than 10 kilometers from the desert.

Having lived a nomadic life around the desert since childhood, Mr. Baddirge testifies to the changes in his surroundings. When Mr. Baddirge was a child, the forest was thick with trees, but now it has become a desolate stone mountain.

An interview with nomadic Mr. Makmarsureng at the site where he planted 30 trees.

The desert is widening and the sandstorms are getting stronger. Mr. Makmarsureng, a nomad whom the reporting team met, says that a murderous sandstorm hit the village two years ago. Hundreds of nomads were killed in sandstorms powerful enough to completely block out the midday sun.

Makmarsureng’s family planted 30 trees near their house to alleviate the damage of a sandstorm that may come once more.

The results weren’t great. Within a year, most of the trees had been blown away by the wind. The land left behind looked more barren.

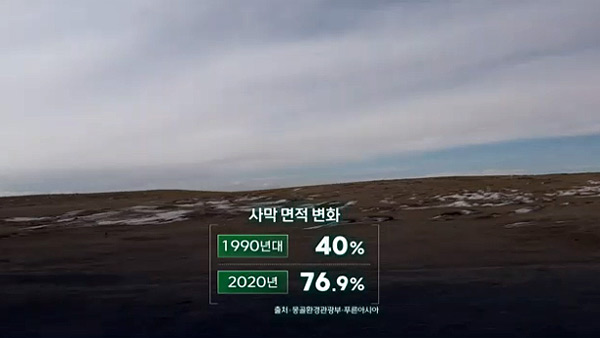

Mongolia’s severe desertification is also reflected in statistics. Thirty years ago, deserts in Mongolia accounted for regarding 40 percent of the country’s land area, but now they have more than halved and nearly doubled.

Climate change, which is the cause, is also proven numerically. Mongolia’s average annual temperature has risen by 2.25 degrees over the past 80 years, and rainfall has decreased by 8%, drying up the land.

A lake in Bayannor that dried up four years ago

Bayan Nor means ‘land of many lakes’ in Mongolian.

But the lake, where village children skated in winter, completely dried up four years ago. Five of the nine lakes around the town have disappeared since the 1990s, and the rest are drying up rapidly.

Mr. Yingh Tour, a nomad who has been moving north for the second year

Climate change in Mongolia is putting nomads off their horses.

Once the team found thousands of goats and sheep, they slowed down and started looking for the nomads. There were many things I wanted to ask.

I mightn’t see anything with my eyes, which have less than 1.0 corrected vision, but the Mongolian knight was different. He asked the nomads he met where they were heading.

They were all moving further north. This is because the desertification in central Mongolia as well as in the south is progressing rapidly, and the grass to feed livestock is disappearing.

‘Zod’, which means disaster in Mongolian, refers to a phenomenon in which livestock die in droves due to heavy snowfall.

Average temperatures have risen, but winter cold has become more severe. Mongolians call the severe cold wave ‘Zod’.

In the video filmed when Zod struck in the winter of 2016, numerous livestock such as cattle and sheep were killed in droves.

A garbage dump in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia.

Many nomads give up their nomads and flock to the cities. There is not much that nomads who have raised livestock all their lives can do in a big city.

It is a garbage landfill on the outskirts of the capital, Ulaanbaatar.

I went inside the landfill. As the trucks kept coming in and dumping out new trash, I might see them picking up sappers and money in rags.

Some of the nomads who flock to the cities make a living by picking up and selling recyclables in landfills.

Mongolian authorities say 600,000 nomads are flocking to the capital so far, or 45,000 each year.

It is estimated that many of them are living in gerchons on the outskirts of the capital, which are regarding 25% of the price of a house in the center of the city.

Mr. Ariontoya, who moved to the capital from the Bolgang region of Mongolia four years ago.

This is Mr. Ariontoya, a nomad who came here following giving up his nomadic life 4 years ago. Her husband drives a taxi, and Arion Toya works for a local public agency. Working couples are better off, but they can’t help but miss the grassland life.

Meadows that remain only in paintings and photographs. In the summer, they sleep in the ger installed in front of their house and reminisce regarding life in the meadow, where they made friends with the sky and the land.

Nomads who have lived raising sheep and horses for thousands of years. They have lived a life that has nothing to do with greenhouse gas emissions, but they are now hit by the bomb of climate change.

Bayang Norsom plantation managed by NGO Pureun Asia

Efforts to stop desertification in Mongolia are ongoing. This forest was created on an area of 54 soccer fields supported by the Korean NGO Green Asia. This forest is a dyke that protects the village from the sea of sand.

When the forest grows, it blocks the wind, and because it moistens the dry land, it prevents desertification to some extent. In fact, residents of Bayang Nor, where 2,000 people live, say that the sandstorm has stopped blowing since they planted the tree.

The Mongolian government is trying to resist the desert by planting a billion trees. But the sea of sand is too wide, and it will likely become even wider if we don’t stop climate change. The yellow dust from Mongolia that blows into Korea will also increase. This is why we should be interested in Mongolia’s desertification.