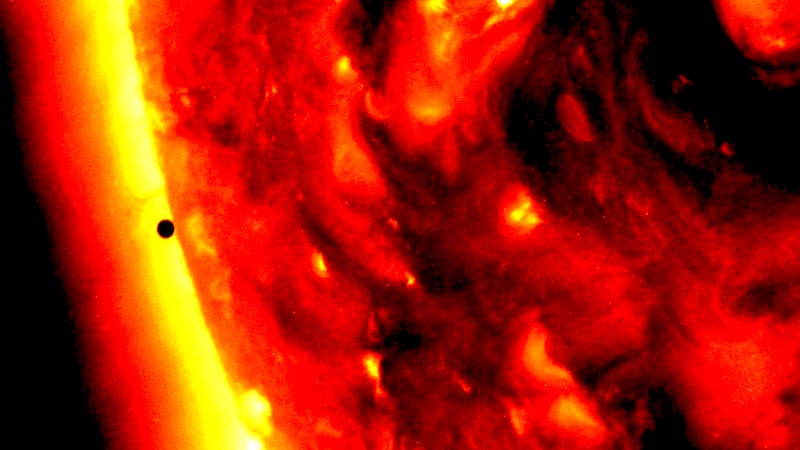

This impressive solar flare may have created a temporary atmosphere, and even added matter to Mercury.

The Sun projected a gigantic wave of plasma on Mercury, this Tuesday, April 12. The powerful flare, known as a coronal mass ejection (CME), was seen emanating from the far side of the sun on the evening of April 11 and took less than a day to hit Mercury.

The event most likely triggered a geomagnetic storm on the planet closest to the Sun, eroding its surface not on the same occasion.

A planet exposed to solar winds

Mercury, the smallest of the planets in the system, does not have a very strong magnetic field, unlike Earth. Moreover, it is closer than us to the Sun and therefore to its plasma ejections. Mercury was consequently stripped of any permanent atmosphere. And has been for a long time.

« The main differences [avec la Terre] are the size of the planet and Mercury has a weak magnetic field and virtually no atmosphere. »

Hui Zhang, professor of space physics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute

Its residual atmosphere is constantly being lost to space, forming a comet-like tail of ejected material behind the planet. Paradoxically, solar flares constantly replenish these small amounts of atoms, giving it a thin layer of fluctuating atmosphere.

See also > BepiColombo delivers its first images of Mercury

Solar flares, a phenomenon still poorly understood

The plasma wave came from a sunspot. It’s one of those areas outside the sun where strong magnetic fields, created by the flow of electric charges, knot together before suddenly breaking apart.

More precisely, solar flares are caused by a buildup of magnetic energy in areas of intense magnetic fields, at the level of the solar equator, probably following a phenomenon of magnetic reconnection.

Scientists pay particular attention to solar storms. They can have real consequences on our planet and in particular on our technologies. At the end of last October, a powerful solar flare had also erupted from our staralerting NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO).

Unfortunately, it is difficult, if not impossible, for scientists to predict the exact duration and strength of an eruption, because the mechanism behind the phenomenon is not well understood. This is one of the reasons why the Parker Solar Probe approaches the sun until it “touches” it. Hoping to collect data that would help us unravel this mystery.

Source : Space