Yoshiko Mibuchi (1914-1984), Japan’s first female lawyer, served as the inspiration for the protagonist in the NHK TV series “Tiger Wings.” After World War II, she became a judge and was involved in the “Atomic Bomb Tribunal,” which determined that the United States’ use of atomic bombs was “a violation of international law.” The ruling in 1963 significantly influenced efforts toward nuclear disarmament and support for atomic bomb survivors both in Japan and worldwide. Now, 79 years after the atomic bomb was dropped, it is essential to reflect on the implications of this ruling, especially as concerns about nuclear weapon use persist. (Yamada Yuichiro)

◆The World’s First Ruling Declaring the Atomic Bomb a Violation of International Law

“The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki constituted indiscriminate attacks on defenseless cities and were illegal acts of war per international law at that time. The suffering inflicted by the atomic bomb was more intense than that caused by poison or gas and caused unwarranted pain. It breached the fundamental principles of warfare laws and was expressly forbidden.

On December 7, 1963, the Tokyo District Court (Presiding Judge: Toyomasa Ozeki) ruled that the United States’ bombings were not permissible.

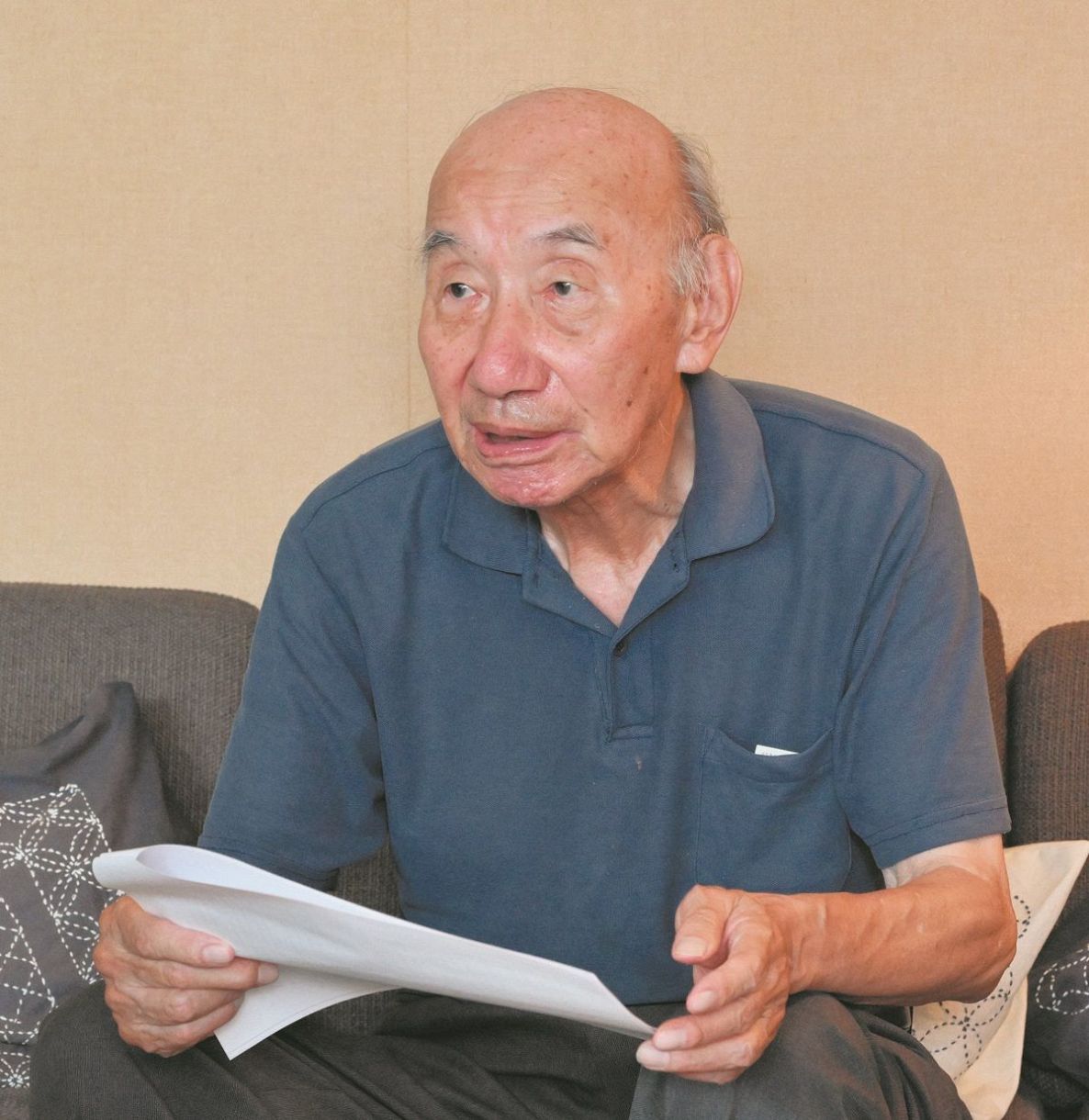

This decision is acknowledged as the world’s first ruling declaring the atomic bomb’s use as a violation of international law. The recent Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) was still fresh in public memory, raising the threat of nuclear conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. “The United States was a superpower, and for the court—part of a defeated nation—to openly criticize the military actions of the victorious country required substantial courage,” recalled former judge Akira Takakuwa (87). Takakuwa handled the case just before the final arguments concluded and authored a 130-page ruling.

◆The Japanese Government Claimed That the Use of the Atomic Bomb Accelerated the War’s Conclusion

In 1955, two lawsuits initiated by five atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki against the government in Tokyo and Osaka were combined. The plaintiffs asserted that the bombings violated international law. Since the San Francisco Peace Treaty relinquished the right to claim compensation from the United States, they sought compensation from the Japanese government based on property rights assured by the constitution.

The defendant, the Japanese government, contended that this did not constitute a breach of international law. In wartime between nations, no country can be held accountable under domestic legislation, and individual atomic bomb survivors cannot pursue claims based on international law. During the case, it was argued that the atomic bomb’s deployment expedited Japan’s capitulation, avoiding the prolongation of the conflict that could have incurred additional casualties on both sides.

Mr. Jin Yuan oversaw the consolidated litigation and was the sole individual to participate in all nine oral arguments throughout the debate. Although he had been reassigned to the Tokyo Family Court by the time the verdict was delivered, the signature of the middle judge was preserved at the conclusion of the original ruling.

◆ “There Was No Justification for Dropping the Atomic Bomb”

“He was a gentle and kind person,” recalled Gao Sang. The presiding judge led the court proceedings in chronological order, with members seated on the right and left. At the time, Gao Sang, who occupied the left seat, was 26 years old, while Ren Yuan, positioned on the right, was in his 40s. “I wrote the draft and circulated it to the presiding judge Gu Guan. I am unsure whether the presiding judge or Mr. Ren Yuan read it first.”

“This was a unique case, entirely different from typical civil cases involving atomic bomb matters. At the time, I felt I was overseeing a remarkably challenging trial,” Gao remarked. “The draft was handwritten, requiring great effort. Due to its length, some sections were modified, but the core structure of the draft remained intact.”

What kind of discussions did the three judges have? In Yuhikaku, a female lawyer looks back on her career without mentioning specific cases. Takakuwa remarked, “I cannot disclose details due to the confidentiality of deliberations,” but shared his reflections on the verdict. “Regardless of whether it constituted a breach of international law or not, there were methods to dismiss the compensation claim; however, we did not avoid this issue but instead reasoned through and examined international law. Ultimately, there was simply no justification for dropping the atomic bomb.”

◆ Although the Government Bear No Liability for Compensation, “I Cannot Help But Regret the State of Politics.”

The trial extended over eight years, hearing from three international law experts procured by both the plaintiffs and the defendant. Two determined that it was “a violation of international law,” while the third “firmly believed it to be an illegal act,” with no expert concluding it was lawful. However, interviews with the plaintiffs intended to clarify the reality of the atomic bomb’s impact were not conducted.

While the ruling did not acknowledge governmental liability for compensation, it conveyed in its concluding remarks that “the war initiated by the state, through its own power and accountability, resulted in the deaths, injuries, and insecurities of numerous citizens.” It stressed the necessity for action to support atomic bomb survivors. Regarding this duty, it stated, “The legislative branch, represented by the Diet, and the executive branch, led by the Cabinet, must fulfill this responsibility.” Concluding, it noted, “In reflecting on this lawsuit, one cannot help but lament the state of politics.”

Mr. Takakuwa explained why the ruling imposed stringent demands on the government. “After the war, many peoples’ homes were destroyed, and starvation became prevalent, yet the government offered no assistance whatsoever. This lack of support extended to atomic bomb victims, as well as victims of air pollution. The government failed to fulfill their obligations, and this situation persists today.”

◆ “This May Reflect the Anger of the Three Judges.”

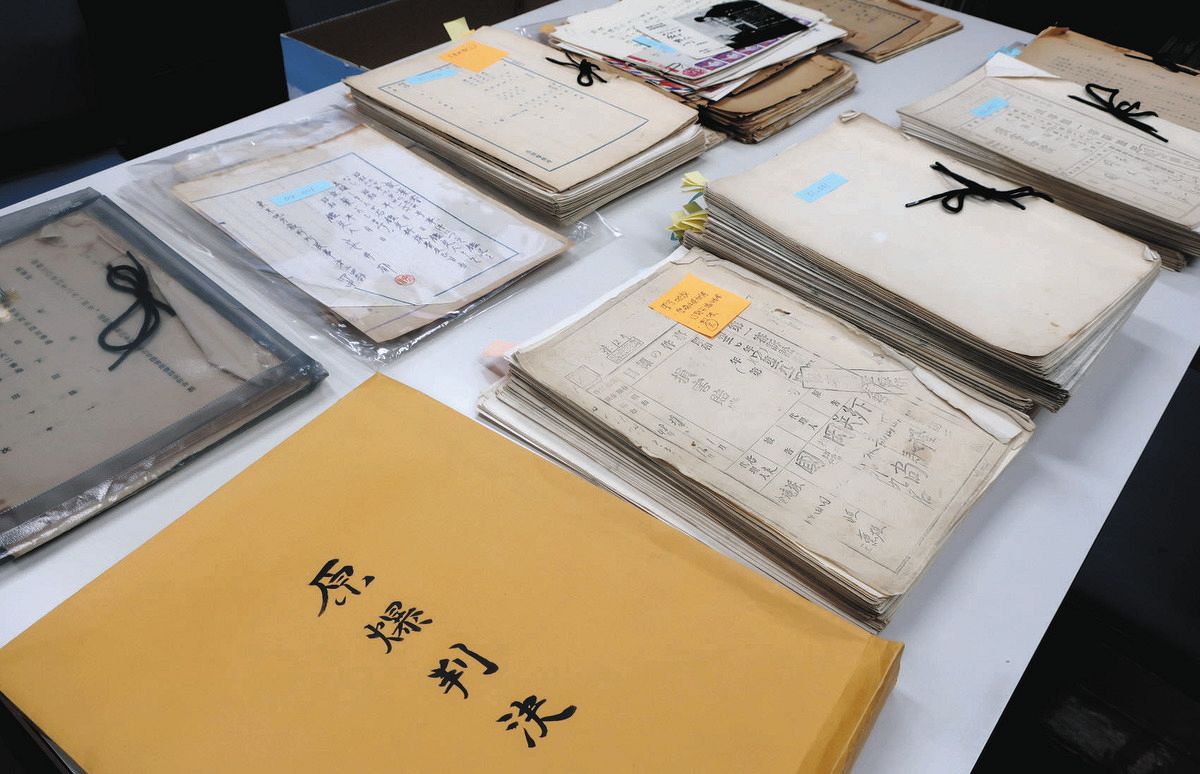

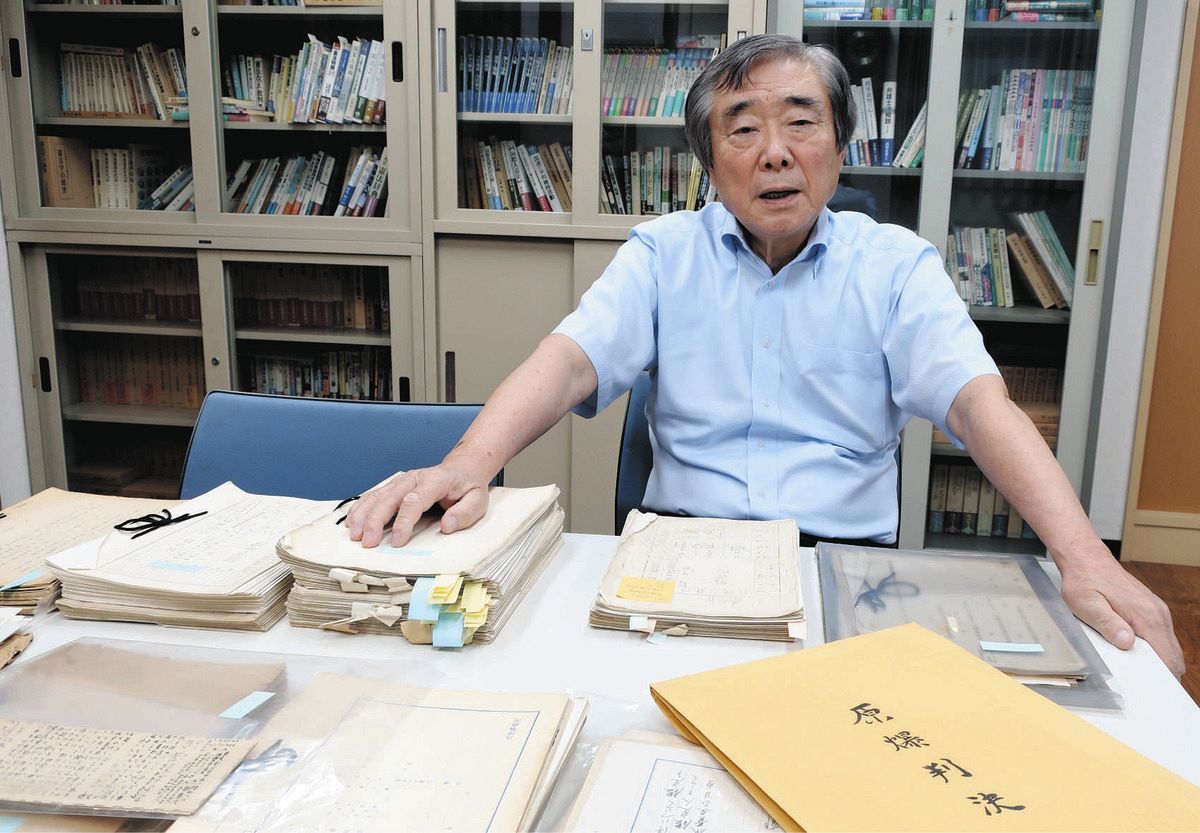

Currently, the Japan Anti-Nuclear Lawyers Association maintains the complaint, oral arguments, expert opinions, and other litigation documents, making them publicly accessible on its website. Established in 1994, the first president of the association was the late Matsui Yasuhiro, who represented the atomic bomb plaintiffs. The current fifth president, Attorney Kenichi Ohku (77), has held this position for about 15 years, commissioned by the Matsui family.

“During the hearings, the Japanese government merely countered the U.S. arguments justifying the atomic bomb. The term ‘political poverty’ pertains to the three judges, and I believe it encapsulates the people’s anger,” Okubo noted.

The plaintiffs did not appeal the first-instance decision. “Although this request was not granted, we are concerned that some have suggested this ruling violates international law.” While the ruling is groundbreaking, the trial primarily revolved around legal arguments regarding its compliance with international law. Okubo expressed regret, stating, “I wish we had done more to highlight the reality of the damage inflicted by the atomic bomb.”

◆ The Ruling That the Bombing Violated International Law Will Affect Future Relief for Atomic Bomb Survivors

Nevertheless, the ruling influenced subsequent efforts to support atomic bomb survivors. With the enactment of the Atomic Bomb Special Measures Law in 1968 and the Atomic Bomb Survivors Support Law in 1995, a framework for certifying atomic bomb-related diseases was established, and support increased gradually. A class action lawsuit regarding recognition of atomic bomb diseases revealed the long-term impacts of atomic bomb radiation on survivors.

The ruling also has international significance. It was translated into English and named the “Shimoda case” after the plaintiff. It is believed to have influenced the 1996 advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which determined that the use of nuclear weapons “generally violates international humanitarian law.” Based on this opinion, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted in 2017, though the Japanese government has not yet ratified it.

Hiromi Tanaka (92), a representative of the Council of Japanese Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb Victims Organizations (Hardenkyo), who was 13 when the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, stated, “During the campaign at the International Court of Justice, I was astonished by the advisory opinion affirming that atomic bomb tests violated international law. This ruling provided us immense support.”

Okubo emphasized the need to reiterate the importance of this ruling. “While this ruling is foundational for nuclear disarmament and victim support, nuclear weapons still exist, and the risk of their use is escalating. For those affected by the ‘black rain’ in Nagasaki, achieving compensation remains elusive, and we must reconsider how to address the challenges posed by atomic bomb tests.”

◆Desktop Memo

61 years ago, the Tokyo Shimbun reported the verdict. Regarding military pensions, a plaintiff remarked, “It is utterly unreasonable to claim there is no assurance for those who lost family members in the atomic bomb explosions and that they cannot thrive even if they survive.” The “political poverty” that disregards victims continues to exist. We must persist in striving towards comprehensive relief. (Book)

Yoshiko Mibuchi and the Historic Ruling on the Atomic Bomb

Yoshiko Mibuchi (1914-1984), renowned as Japan’s first female lawyer, was the inspiration behind the main character of the NHK TV series “Tiger Wings.” After World War II, Mibuchi transitioned to a judge and participated in the landmark “Atomic Bomb Tribunal,” which concluded that the United States’ use of atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a “violation of international law.” This pivotal ruling, articulated on December 7, 1963, not only had significant implications for nuclear disarmament but also provided relief for atomic bomb survivors, both domestically and internationally. As we reflect on the nearly 80 years since the atomic bomb’s devastation, it is essential to examine the enduring significance of this ruling in our ongoing struggle against nuclear weapons.

◆ The World’s First Ruling: Atomic Bombs Violate International Law

The Tokyo District Court, led by Judge Toyomasa Ozeki, stated unequivocally that, “The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was an indiscriminate bombing of undefended cities and an illegal act of war under international law at the time.” This groundbreaking judgment outlined how the bombings inflicted suffering exceeding that of chemical weapons, violating the fundamental principles of just warfare.

On that historical day in December, 1963, the court declared for the first time globally that the atomic bombing constituted a breach of international law. The ruling emerged during a period where global tensions were heightened due to events like the Cuban Missile Crisis. Former judge Akira Takakuwa, recalling that moment, noted that it took immense courage for the court—a national entity of the defeated nation—to publicly reprimand the actions of the victorious superpower.

◆ The Japanese Government’s Position Post-War

Following the bombings, the Japanese administration argued that the use of atomic bombs was necessary to expedite the end of the war and minimize casualties. In 1955, the government faced lawsuits from atomic bomb survivors, who claimed the bombings violated international law. They sought compensation from the government, primarily because the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty waived direct claims against the U.S.

The Japanese government countered that the bombings were justifiable within the context of international law and an essential measure to ensure Japan’s surrender. This defense raised significant legal questions about accountability in wartime actions and the rights of individuals against state decisions.

◆ “There is No Justifiable Reason for the Atomic Bomb” – Insights from Judges

The trial, regarded as a complex legal battle, involved the judges examining numerous legal arguments regarding the bomb’s use. Gao Sang, one of the presiding judges, noted the profound gravity of the case, stating, “This was a special case, completely different from ordinary civil cases.” The judges worked meticulously through drafts, ultimately affirming that there was “no reason to drop the atomic bomb.”

◆ Political Accountability and the Call for Victim Support

Despite the lack of a ruling holding the government liable for compensation, the court emphasized that “the war launched by the state through its own power and responsibility caused the death, injury, and insecurity of many citizens,” articulating the responsibility of the government to rescue atomic bomb survivors. The ruling concluded with poignant reflections about the political landscape, highlighting a “poverty of politics” in ensuring adequate support for victims.

◆ Legacy of the Ruling and Its Global Implications

The ruling on atomic bombing in Japan set a significant precedent not just domestically but also internationally. Currently preserved by the Japan Anti-Nuclear Lawyers Association, it encompassed the complaint, oral arguments, and expert opinions, reflecting a broader movement against nuclear armaments. The judgment influenced later international legal responses, including the advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice in 1996, which articulated that the use of nuclear weapons “generally violates international humanitarian law.”

As the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted in 2017, discussions surrounding nuclear disarmament remain critical. The ongoing advocacy for the recognition and relief of atomic bomb survivors is vital as voices like Hiromi Tanaka, a representing member of the Council of Japanese Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb Victims Organizations, resound in support of international acknowledgment and reparations.

◆ The Ongoing Struggle for Recognition and Support

Despite the legal victories achieved, activists and survivors continue to experience challenges related to compensation and governmental accountability. The Atomic Bomb Special Measures Law enacted in 1968 and subsequent support measures iterated a need for continued advocacy and social mobilization. The sentiments of survivor communities reflect ongoing grievances and the urgent necessity for political actions that affirm the lessons learned from the atrocities of the bombings.

◆ Desktop Memo: Reflections on Political Poverty

Reflecting on the past, one survivor articulated the absurdity in denying guarantees for families impacted by the atomic bomb, lamenting the “political poverty” that continues to ignore victims. This perspective underscores a broader demand for comprehensive support and recognition for all those affected, ensuring that the failures of previous administrations are addressed in present governance.