2024-03-25 06:53:00

The Dutch dredging companies Van Oord and Boskalis are winning large contracts all over the world. Such as in the South Asian archipelago of the Maldives, in Indonesia, Mozambique, Brazil and the Philippines. For example, with their ships, maritime service providers can create land where there used to be sea, thus contributing to new infrastructure. These are lucrative but also often controversial projects, which can put pressure on nature and vulnerable people.

Seven projects from Boskalis and Van Oord are listed in the report Dredging Destruction from human rights organization Both Ends and international partners, which will be published this Monday. According to the organizations, these projects pay too little attention to residents, human rights and nature. That would be contrary to international guidelines for multinationals.

The government guarantees

They explicitly point to the role of the Dutch government, which provides financial guarantor for such large projects. This is done through Atradius Dutch State Business, the Dutch export credit insurer. Through this financier, the Dutch state supports Dutch companies that export. The dredgers are Atradius DSB’s largest customers. Between 2012 and 2023, the Netherlands provided 8.4 billion euros in insurance to Van Oord, Boskalis and their financiers for such projects, Both Ends and partners calculated.

Atradius should pay much closer attention to the harmful consequences of the projects they support, according to environmental organizations. They call it a misunderstanding that Dutch companies work more carefully than, for example, Chinese competitors. This topic will be on the agenda in the House of Representatives on Wednesday. The Committee for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation will then receive representatives of civil society organizations from Mozambique and Indonesia.

Van Oord is participating in a large gas project by TotalEnergies near the coast of Mozambique. This has come to a standstill due to unrest and violence in the region. According to the report, 600 families were forced to make way and the work is damaging nature. In Indonesia, Boskalis helped build five artificial islands off the coast of Makassar, South Sulawesi. According to the report, 43 families were evicted without compensation. Valuable nature has also been destroyed, the organizations say.

Lack of space in the Maldives

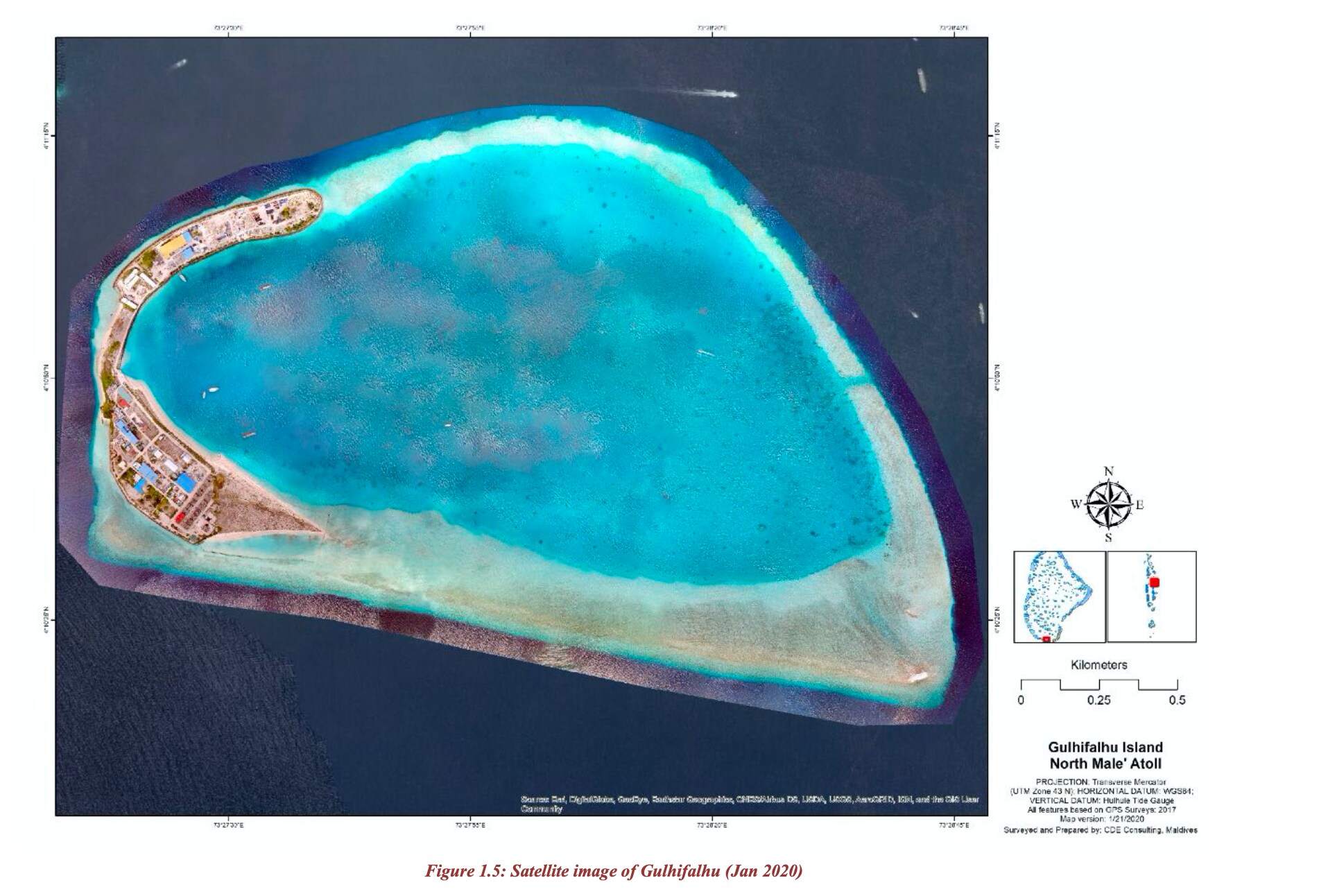

The necessary contracts can also be won in the Maldives, the beautiful archipelago south of India, with a population of half a million people. Boskalis is involved in the construction of a new port on the island of Gulhifalhu. For this purpose, a large part of the inland lake, the beautiful lagoon, is filled with sand.

Since June, 128 hectares of land have been created, Minister Abdulla Mutthalib of Construction and Infrastructure said on Wednesday. He expects Boskalis to complete the 150 hectare job next month. President Mohamed Muizzu believes that Gulhifalhu should then be expanded by another 85 hectares, because the Maldives has a housing crisis.

“The Gulhifalhu Lagoon is being lost as coral habitat, due to the permanent development of an international port at this location,” reads the project’s official website. “After coral reef ecosystems are affected, recovery usually takes many years.” That is why thousands of coral colonies have been moved, in collaboration with the local organization ReefScapers, the website reports. A rescue operation whose success must be proven.

According to local environmental organization Save Maldives – involved in the report – the destruction of coral reefs through land reclamation is a tragic mistake. The organization filed a lawsuit in 2021 to prevent the project development and environmental damage. There was another hearing last week. But Boskalis’ dredging work is almost complete. Photos from Save Maldives this month show how Boskalis’ Willem van Oranje dredger is clouding the water, which is bad for corals.

Van Oord is also active in the Maldives. It has created 194 hectares of new land in a nature reserve that is special in the eyes of UNESCO: the Addu Atoll, consisting of thirty islands, seventeen of which are uninhabited. An atoll is a ring-shaped island with lots of coral, or a group of such islands. “This biosphere reserve has an impressive reef ecosystem with exceptional biodiversity that includes more than 1,200 fish species,” UNESCO wrote a few years ago.

The work should turn Addu City into a fully-fledged city, a thriving economic center and attractive tourist destination, Van Oord wrote. The city is also better protected once morest climate change. 20,000 people live on Addu Atoll. “With the project, the government wants to boost the economy and tackle high unemployment,” said Van Oord. The project has been completed and is not included in the report because no export credit insurance was provided.

Save Maldives is critical of its own government, which is said to speak with ‘double tongue’. On the one hand, it warns that the climate crisis threatens the island and causes bleached corals, while on the other hand, it itself initiates land reclamation projects in which coral reefs and other nature have to make way.

Effects need to be investigated

Just as states must protect human rights, companies must respect human rights. The United Nations writes this in the guidelines for international companies. This means that companies must structurally investigate the possible negative consequences of their activities and how they may violate human rights. There must be a complaints desk for victims, who are also entitled to compensation and recovery in the event of damage suffered.

Companies cannot point the finger at their client, but must investigate the effects of their activities themselves. Last year, the OECD standards were tightened: they now clearly state that companies must make an effort to preserve biodiversity.

Both dredging companies say research has been carried out into the consequences of the work in the Maldives and that coral has been saved by moving it. Van Oord initiated the Ocean Health program in 2020. “Our focus is on boosting biodiversity and creating healthier oceans by preserving, restoring and creating marine ecosystems,” the company says.

If you want to boost biodiversity, wouldn’t it be easier to let existing coral reefs exist? Isn’t that how you create healthier oceans? In response to questions, Van Oord refers to the project website. Boskalis does not answer questions regarding the projects in the Maldives and how it protects biodiversity in its business operations.

Departure from the Netherlands

Boskalis CEO Peter Berdowski is critical of legislation that requires companies to practice corporate social responsibility. Last year he threatened to leave the Netherlands if such a law were introduced. The court might then assess whether companies’ activities have negative consequences for human rights, labor rights or the environment. This law did not pass in the Netherlands, but an agreement was reached in Europe in March. Boskalis announced this month that it is considering moving its registered office from the Netherlands to Abu Dhabi.

These UN and OECD guidelines also apply to Atradius DSB, which supports the dredging companies on behalf of the Dutch government. According to Both Ends, the projects are approved too easily and the assessment is shady. There is a lack of transparency, while according to the OECD, companies should be open regarding the negative effects of their activities and the measures they take once morest them. Too many documents are labeled ‘trade secret’, Both Ends believes.

Atradius says it cannot publish third-party company information that it does not own. The financier says it has a good policy to take environmental and social aspects into account when providing insurance. Employees went to see the Maldives for themselves last year. By then, export credit insurance had already been granted to Boskalis.

“We have seen on site that the relocated corals have clearly grown over the past three years and that a new ecosystem with reef fish is developing there,” a spokesperson emails regarding that visit. But there is no public scientific substantiation to read. The so-called monitoring evaluation is confidential, the spokesperson says.

Compensation for destroyed nature

If companies have to protect biodiversity, to what extent is dumping a lagoon full of sand appropriate? How do you ensure that the new ecosystem becomes equivalent to the old one? Who determines this and what happens if the new coral reef does not meet expectations?

“The biodiversity value of the area where the project takes place must remain the same or increase if you want to meet international standards,” says the Atradius spokesperson regarding compensating for the destroyed nature. “A detailed plan is provided for this by the project team and independent experts assess and monitor this plan. If expectations are not met, a new approach will be considered with all parties involved.”

Is it realistic to create an ecosystem in the Maldives that is equivalent to the disappeared nature? Atradius puts it carefully: “In the long term, this might be achieved, based on external advice from experts and information provided.”

Also read:

100 million passengers will soon land in the Wadden Sea near Manila

The Netherlands is helping the Philippines with the sustainable development of Manila Bay. Yet fishermen suddenly have to make way for a gigantic airport in the sea.

How sustainable is Atradius DSB? ‘You can say that we change character’

What are the large companies doing to improve sustainability? Trouw asks several concerns. In this episode: director Bert Bruning of export credit insurer Atradius DSB. “We’re starting to look like a venture investor.”

1711432199

#Dutch #company #filling #coral #lagoon #Maldives #sand