Even today, Indian Dalits assert that the path to true liberation from entrenched discrimination—and the opportunity to amass significant wealth—lies in venturing into self-employment and entrepreneurship.

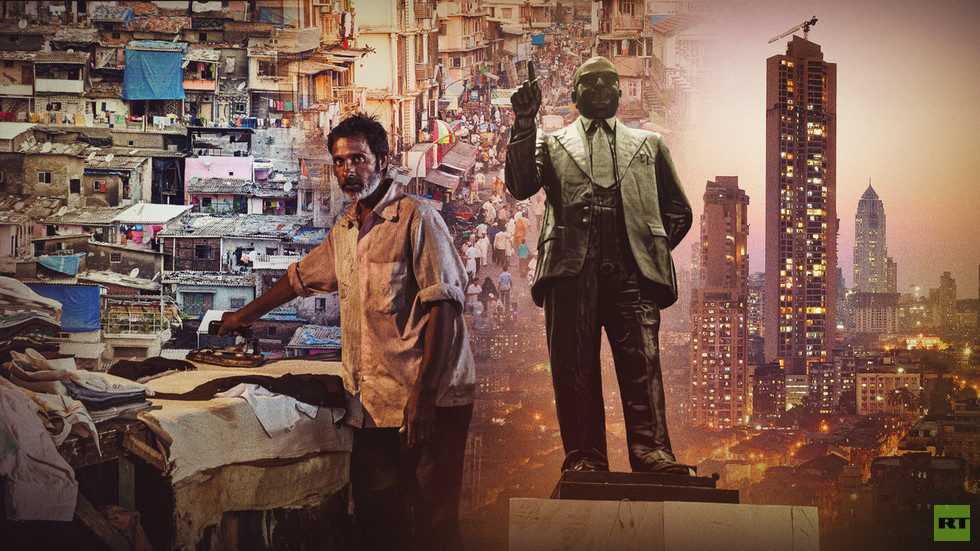

What connects Nilam G, a 23-year-old entrepreneur hustling from her home in a Mumbai slum, to billionaire Ashok Khade? Both are Dalits, originating from communities that have endured a legacy of caste-based oppression, historically relegated to the lowest tier in India’s intricate social hierarchy.

Historically labeled as ‘untouchables’ or ‘outcastes’, the British colonial administration grouped them under various classifications, initially termed ‘depressed classes’ and later ‘scheduled castes’. For centuries, Dalits have been shackled to societal roles that included degrading professions such as manual scavenging and handling corpses. Consequently, this cultural branding branded them as ‘impure’, further entrenching their untouchable status.

As a result, for centuries, our society’s higher castes maintained a strict distance from Dalits, often going to extreme lengths, such as bathing if a Dalit’s shadow inadvertently fell on them. They lived in conditions of extreme exclusion, barred from entering residential spaces, shelter homes, temples, and public spaces such as markets. Children from Dalit families faced harassment, with even the simplest interactions like playing with or marrying into higher castes being disallowed. In academic settings, Dalits were often relegated to the back rows of classrooms and have been subject to bullying, as showcased by tragic cases where students faced ridicule in elite educational institutions.

Although the Indian Constitution was adopted after the country gained independence in 1947—crafted with significant input from a Dalit—challenging the deeply ingrained caste hierarchies remained a formidable task for the Dalit community. However, in recent years, a notable shift has occurred as many Dalits choose to step into entrepreneurship—a decision fueled by the recognition that self-employment may offer the best chance for economic advancement and improved job opportunities. As of now, over 680,000 micro, small, and medium enterprises are being managed by individuals from scheduled castes and tribes, a number that comprises approximately 7% of the overall total. Dalit political representatives affirm that this surge can be seen as a burgeoning realization among scheduled castes that only Dalit entrepreneurs can craft better livelihood prospects, especially in today’s flourishing SME sector.

Unbeknownst to her, Nilam G has embraced one of the core tenets of the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s (DICCI) philosophy—to transform marginalized groups into “job-givers, not job-seekers.”

In the lead-up to Diwali, numerous homes within the cramped confines of suburban Mumbai’s Jagruti Nagar were brimming with hundreds of meticulously hand-painted ‘diyas’, tiny oil lamps crafted from clay, eagerly awaiting packaging and dispatch to eager buyers.

“We’ve previously ventured into selling homemade chocolates, and as Christmas approaches, we’re exploring candle-making,” Nilam explained, adding, “but locating guidance or resources to upscale our business remains a challenge.” She inadvertently unearthed a significant obstacle faced by many Dalit entrepreneurs.

“The dearth of information regarding government schemes, working capital, credit, banking, and marketing continues to be a major hurdle preventing greater entrepreneurial success among lower caste individuals,” remarked Kavita Dambhare, a Nagpur resident and founder of Flight India, a non-profit organization that has supported nearly 80,000 beneficiaries in establishing agro-based enterprises over its 25-year history.

Dambhare vividly recalls the harsh poverty that marked her childhood, where her after-school hours were consumed with tasks like gathering fodder for the family’s dairy cows, delivering milk, and caring for livestock to support her father. When she sought employment, she was met with an overwhelming reality—tens of thousands contended for every available job opportunity.

“If I advanced on my own, it wouldn’t yield widespread progress,” she declared, asserting her commitment to creating sustainable livelihood and entrepreneurial avenues for Dalit and Adivasi women in rural sectors.

Dambhare’s endeavors encompass an extensive process of assessment to identify ventures with the highest chances of success in various rural contexts, crafting loan applications, steering clients through banking protocols, governmental regulations, and providing essential training and skills development for Dalit women entrepreneurs.

Many of the thousands of Dalit businesspeople she nurtured have entered the dairy sector, running poultry farms, or raising goats; others have established food ventures that produce homemade pickles or packaged snacks. The majority operate through self-help collectives, with agriculture-related industries being the most resilient and stable, according to Dambhare.

Nevertheless, the specter of discrimination lingers, with many individuals in India still reluctant to purchase goods from a Dalit vendor due to unfounded fears of transmitting ‘impurity’.

“Regardless of whether rural women entrepreneurs produce traditional items or innovative products, their clientele will predominantly arise from local elites, thus maintaining a systemic dependency on them,” Dambhare pointed out.

The imbalanced caste dynamics in this marketplace allow upper caste buyers to consistently drive down prices for Dalit-produced goods. “Promoting products and accessing broader markets poses enormous challenges for Dalit entrepreneurs,” Dambhare lamented, noting, “This barrier feels almost insurmountable.”

However, collectives operating as businesses have achieved notable success. For instance, Dambhare reminisced about an initiative she spearheaded in 2000 that facilitated the creation of multiple rural women’s small savings groups in the remote forest regions along the borders of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh.

For extended periods, tribal women had disposed of the seasonal mahua flower, a small aromatic bloom from the Mahua tree (Madhuca longifolia), for a meager 2 rupees ($0.024) per kilo. Highly esteemed for its cultural and economic significance, dried and processed mahua flowers are used in the production of a traditional alcoholic beverage, alongside various medicinal and culinary applications. “By pooling the women into self-help collectives and storing this seasonal forest produce for a few months, we increased their bargaining power, yielding 8 rupees [$0.096] per kilo from traders during that initial year,” she recalled.

Dambhare’s latest initiative aims to involve Dalits in the promising field of soil testing, an emerging area as farming communities seek organic and natural farming solutions to combat climate change. “We have processed loan applications for 50 prospective soil-testing labs,” she shared, adding, “80% of these applicants are Dalits.” The approvals are anticipated shortly.

In urban areas, entrepreneurs whom she has mentored now operate flour mills, retail shops, tailoring businesses, incense production units, among various other ventures.

Approximately 50-year-old Prithviraj Borkar from Nagpur prepares for his annual pilgrimage to Mumbai on December 6, a day marked by Dalits to honor Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s ‘Mahaparinirvan Din’ or death anniversary. Born into a Dalit family, Ambedkar was the principal architect of the Indian Constitution, who converted to Buddhism in 1956, rejecting the caste-based oppression epitomized by Hinduism. Annually, nearly 500,000 Dalits journey to Mumbai on this date to pay homage at the site of Ambedkar’s cremation and browse through numerous stalls set up in the vicinity.

Borkar, the founder of Shakyamuni Tours & Travels Ltd established in 2010, has showcased his stall there for several consecutive years, with posters prominently displaying international and domestic tours tailored for Dalit travelers, featuring Buddhist destinations throughout the Far East and Sri Lanka, all offered at budget-friendly prices, ensuring accessibility for many first-time fliers among Dalit families.

“My business extends beyond mere profit-making,” Borkar stated regarding his vision for success. “It encompasses a social obligation to enable Dalits to explore the world and comprehend the significance of Ambedkar’s embrace of Buddhism.”

While entrepreneurship empowers Dalits by freeing them from discriminatory employers, it also presents challenges, as market opportunities may be limited, making it difficult to thrive as non-Dalit clientele can be scarce. Borkar acknowledged the stability of his revenues is a result of his offerings being specifically curated for the Dalit demographic, with a keen focus on affordability and cultural resonance.

Despite these challenges, there has never been a more opportune time for Dalits to pursue entrepreneurship, affirmed Raja Nayak, the national vice president of the DICCI. His diverse businesses in the food sector, construction, and logistics amass an annual revenue of 600 million rupees ($7.1 million).

“An ocean of opportunities exists, alongside favorable government policies for entrepreneurs,” Nayak commented. Citing Karnataka as a prime example, he noted the state offers a 75% subsidy on land to Dalits who set up new industries.

The DICCI has collaborated closely with the Indian government to formulate robust policies that endorse Dalit entrepreneurship. Nayak recounted the beginning of his own entrepreneurial journey in the 1990s when, at the age of 17, he sold export-rejected shirts on a sidewalk in southern India’s textile hubs.

“The Stand-Up India program initiated by the finance ministry acts as DICCI’s brainchild, extending loans up to 10 million rupees [$118,400] without requiring collateral from scheduled caste or scheduled tribe entrepreneurs via any nationalized bank.” This marked a stark departure from the barriers faced by Dalits in the 1980s and 1990s, when access to financial resources was the greatest obstacle to starting a business.

With aspirations to expand into Russia, which he identifies as a land of numerous opportunities, Nayak encouraged prospective Dalit entrepreneurs to harness the available state and central government benefits while maintaining a steadfast work ethic. “The world is ripe for business,” Nayak asserted.

The government also launched the National Scheduled Caste/ Scheduled Tribe Hub (NSSH), aimed at enhancing market access and ensuring the active inclusion of scheduled caste entrepreneurs in public procurement processes, empowering Dalit-owned businesses to become suppliers for larger firms and public sector organizations.

Between 2020 and 2023, the Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises of India allocated over 4.35 billion rupees ($51.5 million) towards this initiative, focused on entrepreneur development, integrating service sectors under special credit-linked capital subsidy schemes, formulating strategic social media outreach, and establishing a dedicated cell to assist Dalit entrepreneurs in actively engaging in government tenders and exhibitions. Fifteen decentralized NSSH offices operate in major urban centers and Tier 2 regions to provide essential support for Dalit-owned enterprises, ensuring assistance with tender participation, credit facilitation, and compliance with governmental regulations.

Nonetheless, these measures alone may not adequately empower Dalit entrepreneurs, cautioned Chandra Bhan Prasad, a distinguished Dalit thinker and writer, affiliated with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in the US.

“No policy has truly empowered Dalit entrepreneurs except for the economic reforms of the Nineties, which abolished the Inspector Raj and removed cumbersome licensing requirements that were controlled by upper caste individuals,” Prasad explained. These transformations inadvertently positioned a significant number of Dalits as vendors for larger corporations, born out of changes not specifically aimed at their benefit. “It was an unintended consequence,” he emphasized.

The disconnect between policy-makers and the real barriers that impede Dalit enterprise remains profound, as Prasad lamented the decline of the Dalit Enterprise magazine, which ceased operations during the Covid-19 pandemic due to deteriorating support from Dalit businesses. The current administration has disbursed approximately 3 billion rupees ($35.5 million) via various schemes intended for Dalit enterprises. Yet, without market access, many beneficiaries find themselves unable to honor their debts.

Prasad emphasized, “Dalits are not merely seeking financial assistance; they are demanding equitable market access.” Furthermore, he acknowledged the gap in education and networking compared to their upper caste counterparts, which exacerbates the challenges faced by first-generation Dalit entrepreneurs.

Among the few Dalit entrepreneurs rising to prominence, Ashok Khade stands out as a notable success story. He serves as the managing director of DAS Offshore Engineering Pvt Ltd, an engineering and construction firm valued at 5 billion rupees ($60 million), specializing in critical sectors including hydrocarbons, water supply, and infrastructure development.

Khade grew up as the son of a cobbler, surrounded by profound poverty in Maharashtra’s Sangli district. His journey towards success included years of hardship in Mumbai, where he pursued his education while sleeping under a staircase due to a lack of housing affordability.

His professional beginnings included training and employment at Mazagon Dock Ltd before he launched DAS Offshore in the early 1990s, a company named in honor of the Khade brothers—Datta, Ashok, and Suresh—who were all employed at the dockyard. Suresh Khade later attained political recognition as a minister in the Maharashtra government from 2022 to 2024.

An enduring principle that guided Khade on his path was viewing the accomplishments of his 4,500 employees as a barometer of his company’s success. “It doesn’t matter that I have BMWs today, I must remember the times when I took the train or bus,” he stated, emphasizing that these reflections keep him grounded and connected to his roots. Khade’s advice to aspiring Dalit entrepreneurs stresses the importance of education and a long-term vision for success. “And work with long-term goals in mind,” he added, underscoring the value of perseverance.

What are the systemic barriers hindering the growth of Dalit entrepreneurs despite recent visibility initiatives?

Dged that while recent initiatives have enhanced visibility for Dalit entrepreneurs, systemic barriers rooted in caste prejudices continue to stifle their growth. “Market dynamics still favor the upper castes, and without a fundamental change in consumer behavior, Dalit entrepreneurs will always struggle to compete,” he stated.

The journey toward equity for Dalit entrepreneurs is riddled with challenges, but there are glimmers of hope. Young Dalit entrepreneurs are beginning to carve out niches for themselves, driven by innovation and a fierce determination to overcome adversity. Their resilience reflects a profound desire not only to thrive economically but also to challenge and change societal norms that have perpetuated inequality for generations.

Programs supporting Dalit entrepreneurship, coupled with initiatives aimed at educating consumers about caste-based discrimination, are crucial to dismantling these deeply entrenched biases. Increasing awareness of the potential contributions of Dalit entrepreneurs to local economies could foster a more inclusive marketplace.

while there are significant hurdles for Dalit entrepreneurs in India, the potential for change exists through a combination of targeted government policies, grassroots initiatives, and a shift in societal attitudes towards caste discrimination. Encouragingly, the efforts of individuals like Dambhare and organizations such as DICCI provide a foundation for future growth and empowerment, paving the way for a more inclusive economic landscape.