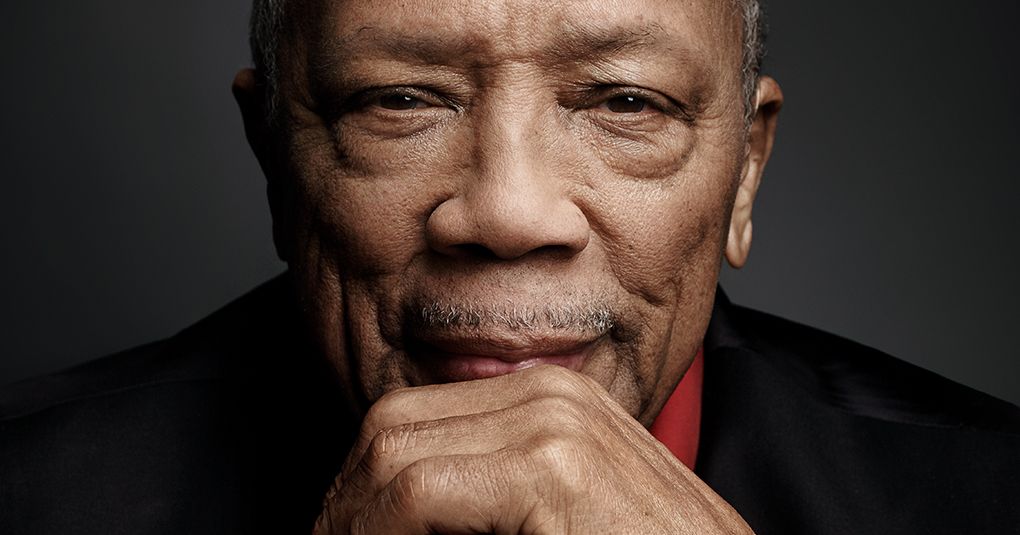

Photo: Art Streiber / AUGUST

Originally published on February 7, 2018, this interview is being republished in light of Jones’s recent passing at the age of 91.

Quincy Jones, a titan in the music industry, has cultivated an image of sophistication and smoothness. Accumulating an impressive collection of 28 Grammy awards and co-producing Michael Jackson’s landmark albums certainly adds to his polished reputation. However, the real Quincy, at 84, reveals a more complex and spirited persona. “All I’ve ever done is tell the truth,” he asserts, relaxed on a luxurious couch in his sprawling Bel Air estate, just moments away from sharing some audacious insights. “I’ve got nothing to be scared of, man.”

As he embarks on an extensive celebratory journey leading up to his 85th birthday in March—with a Netflix documentary and a CBS special featuring Oprah Winfrey in the works—Jones, donned in a cozy sweater and stylish scarf, engages in conversation as if his life depends on it. He name-drops, offers critiques, praises his contemporaries, and spins tales about his circle of renowned friends. His voice carries an irresistible charm even when revealing uncomfortable truths, accentuated by gestures of camaraderie. “The experiences I’ve had!” he marvels, shaking his head as if in disbelief. “You almost can’t believe it.”

How so?

Greedy, man. Greedy. “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough”—the c section crafted by Greg Phillinganes deserved a credit, but Michael should’ve given him 10 percent of the song. To his chagrin, he didn’t.

What about outside of music? What’s misunderstood about Michael?

I used to criticize him about the plastic surgery; his justifications — claiming it was due to a disease — felt like a smokescreen.

How much were his problems wrapped up with fame?

You refer to how he looked? His issues stemmed from how his father instilled a notion of ugliness in him, which contributed to the emotional scars he carried.

It’s such a strange juxtaposition—Michael’s music radiates joy, yet his life feels oddly sorrowful with time.

True, but ultimately, Michael’s struggle was with Propofol, a challenge that isn’t exclusive to fame. The manufactured addiction from Big Pharma, with drugs like OxyContin, poses a grave societal issue. From my years by the Clintons, I came to understand the formidable influence that industry has. This is serious business. What’s your astrological sign, man?

Pisces.

Me too. It’s a great sign.

Recently, you mentioned the Clintons, who are your friends. Why does there remain such intense dislike of them? What are others missing about Hillary that you see?

It’s because when secrets are kept, they don’t tend to work out well.

Like what secrets?

That’s another subject I shouldn’t discuss.

You sure seem to know a lot.

I know far too much, man.

What’s something you wish you didn’t know?

Who killed Kennedy.

Who did it?

That would be [Chicago mobster Sam] Giancana. There existed connections linking Sinatra, the Mafia, and the Kennedys. Joe Kennedy was a notorious figure who sought Sinatra’s assistance in reaching Giancana for votes.

I’ve heard this theory before—that the mob aided Kennedy in winning Illinois in 1960.

Publicly discussing this is unwise. Where are you from?

Toronto.

I was at the Massey Hall show.

Really? The Charlie Parker concert with Mingus and those guys?

Yes, indeed. I later discovered the band earned a mere $1,100. It struck me at the time as just another gig, devoid of historical weight. Even with events like Woodstock, contemporaries were unaware of their mark on history. Elon Musk has been trying to coax me to Experience Burning Man, but I’m not interested. Who could have anticipated Woodstock becoming what it did? Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of the national anthem was legendary.

Wasn’t Hendrix set to contribute to Gula Matari?

He was indeed supposed to play on my album but bailed due to nerves at the thought of performing beside Toots Thielemans, Herbie Hancock, Hubert Laws, and Roland Kirk. Those are some intimidating artists. Toots remains one of the greatest soloists ever.

What was your reaction upon first hearing rock music?

Rock tends to be a white adaptation of rhythm and blues, motherfucker. I crossed paths with Paul McCartney when he was just 21.

What were your initial thoughts on the Beatles?

I believed they were the least skilled musicians ever. They had no technical prowess. Paul was this dreadful bass player, and Ringo? It’s hardly worth mentioning. I recall a studio session with George Martin, where Ringo fussed for three hours over a four-bar part he couldn’t get right. Eventually, we joked, “Mate, why don’t you take a break, grab a lager and lime, and chill for a bit.” He did just that, bringing in jazz drummer Ronnie Verrell, who cleaned up with excellence. Once Ringo returned and listened to the playback, he remarked, “George, could you play it back for me one more time?” To which George complied, and Ringo then mused, “That didn’t sound too bad.” I replied, “That’s right, motherfucker, because it wasn’t you.” A great guy, nonetheless.

Were there any rock musicians who left a positive impression?

I admired Clapton’s band. What were they called?

Cream.

Yeah, they had remarkable talent. But have I got a surprise for you—

Who?

Paul Allen.

Stop it. The Microsoft guy?

That’s right. On a yacht trip of his, we encountered David Crosby, Joe Walsh, and Sean Lennon. A wild gathering of characters! In the closing days, Stevie Wonder joined us, and he urged Paul to perform with him—he’s really good, man.

You mingle within elite circles, and while contributing is vital to you, do you see the ultrarich showing enough concern for the underprivileged?

No. The affluent aren’t doing nearly enough. Most of them don’t care. I emerged from the streets, empathizing with kids lacking resources because I see myself in them. Others haven’t experienced poverty, so they remain indifferent.

As you look back over the last 50 years in your humanitarian work, do you think the country is better off than it was when you first began?

No. We’ve spiraled down to the worst point, yet simultaneously, people are rising up to confront these issues. Feminism is powerful; women are taking a stand. Racism is being fought against. God’s exposing all the darkness to inspire resistance.

The latest revelations about the entertainment industry’s treatment of women have been shocking. Given your extensive experience, do you find these patterns surprising?

No, man. Women have had to endure a mountain of mistreatment. Both women and people of color still contend with barriers in the industry.

What about the alleged misconduct of your friend Bill Cosby? Does that complicate your view of who he is?

It was rampant. Brett Ratner, [Harvey] Weinstein—he’s a disreputable guy. He failed to respond to my serious attempts to reach him, real five calls. A bully.

What about Cosby, though?

What about him?

Were you surprised by the allegations?

We can’t talk about that in public, man.

I’m sorry to jump around—

Be a Pisces. Jam.

If you could change one thing to resolve a pressing issue in this nation, what would it be?

Racism. I’ve watched it evolve from the ’30s and throughout my life. While we’ve made strides, the journey remains long. The South is openly flawed, but at least you know where you stand. Northern racism tends to be concealed. That’s why the current revelations are good—they’re shedding light on once-hidden haters.

What sparked this unrest? Is it solely down to Trumpism?

It’s driven by Trump and uneducated folks rallying behind him. He merely vocalizes their latent sentiments. I’ve spent time with him, and he’s a wild individual—mentally limited, megalomaniacal, and narcissistic. I can’t stand him. I once dated Ivanka, you know.

Wait, really?

Absolutely. Twelve years back, Tommy Hilfiger—working with my daughter Kidada—approached me, saying, “Ivanka is eager to have dinner with you.” I replied with, “No problem. She’s stunning.” Her legs were simply breathtaking. The only issue was her dad.

Would your friend Oprah make a good president?

I wouldn’t advise her to run. She lacks the necessary experience. To lead responsibly, prior roles as a governor or CEO are significant. Without those, it’s tricky to guide people.

She is indeed the CEO of a company.

A conductor knows nuanced leadership better than many business figures—definitely more than Trump, who’s clueless. Real leaders don’t amass enemies like he does. He’s simply an idiot.

Is the state of Hollywood’s race issues as troubling as those permeating the wider nation? Your early experiences as a film scorer faced producers using veiled language against the “bluesy” sound you’d produce. Is this still an issue?

It’s still deeply flawed today. Back in 1964, while in Vegas, certain places were off-limits to me because of my race, but Frank [Sinatra] championed me. Changing perspective requires proactive efforts from white individuals questioning racism among themselves. Every region varies, though. When visiting Dublin, Bono ensured I stayed in his castle due to the rampant racism there. Bono is family to me; he named his son after me.

Is U2 still producing significant music?

[[Shakes head.]

What’s the reason behind that?

Unfortunately, I’m unsure. While I hold deep affection for Bono, the weight of expectation has stifled the band. Bono’s global endeavors with Bob Geldof concerning debt relief remain an unparalleled achievement in my life, akin to “We Are the World.”

Your memoir touches on the discontent expressed by rock artists during the creation of “We Are the World.” Is there more context to that narrative?

It wasn’t purely the rockers. Cyndi Lauper’s manager voiced that “the rockers” disapproved of the track. Understanding how that world operates, we consulted top artists like Springsteen, Hall & Oates, and Billy Joel, to whom they granted high praise. I eventually told Lauper to pack her things if she was unhappy. Curiously, she struggled during recordings because her accessories rattled against the microphone. It was just her opinion causing the fuss.

What do you feel has deserved more attention in your career?

What are you suggesting? I’ve never encountered this issue. Everything I’ve contributed has made waves.

Any musicians you think needed more recognition?

Absolutely. The Brothers Johnson, James Ingram, and Tevin Campbell were phenomenal talents who soared in notoriety.

From a musical standpoint, what project brings you the most pride?

The ability to translate feelings into notated music is rare. Crafting arrangements that allow a band to emulate a singer is a unique talent. I wouldn’t trade that for anything.

Years ago, a quote allegedly attributed to you criticized rap as repeating four-bar loops. Is this a stance you still hold?

That rings true—rap often oversimplifies with repetitive phrases. The ear craves melodic innovation; listeners disengage when music becomes stagnant. Genuine music is curious. Keeping the audience engaged musically is essential.

Is there a collaboration that highlights your belief regarding melodies needing freshness?

Indeed, a prime example of incorporating elements from bebop into mainstream pop is found in “Baby Be Mine.” [[Hums the melody.]It exemplifies a Coltrane spirit within a pop framework, bridging young audiences to classic jazz notions.

Coltrane’s dedication to the Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns is famously known. Was this the book of reference?

Exactly! You’re raising intriguing topics! Coltrane’s entire legacy derives from that thesaurus reference. Notably, the book includes a 12-tone example, which has ties to “Giant Steps.” Contrary to popular belief, Coltrane was indebted to Slonimsky. That book altered the trajectory of jazz improvisation.

When Coltrane began to experiment—

“Giant Steps.”

How about when he ventured further into atonality—

No, no, no. That was also heavily influenced by Alban Berg—the pinnacle of atonality.

So, do you sense jazz’s essence manifesting in current pop music?

Not in the slightest. Musicians sacrificed authenticity in favor of financial gain. When the pursuit of profit supersedes artistry, true creativity evaporates. Throughout my career, I’ve never recorded for fortune or fame—not even Thriller. God leaves the situation when profit becomes the sole motivation; you can spend a fortune on a musical idea without ensuring returns.

Is there any innovation within modern pop music?

No, not at all. Just repetitive loops, beats, rhymes, and catchy hooks. What wisdom can I glean from that? Quality songwriting is paramount; even the greatest vocalist can’t salvage a poor composition. This lesson entrenched itself in me five decades ago, and it remains the most significant insight I’ve gained as a producer. Without exceptional songs, nothing else truly matters.

What stand-out innovation have you made in music?

Everything I’ve accomplished.

Are all your contributions considered innovative?

Absolutely! I take immense pride in the diverse fusion of genres I’ve explored. Since childhood, I’ve performed across a wide spectrum of music genres—from celebratory tunes to marches, adult clubs to jazz, and mainstream pop. I felt right at home producing Michael Jackson’s music.

Of course.

It marked the inaugural celebration of Dr. King’s birthday in Washington, D.C., with Stevie Wonder spearheading the musical direction. After our performance, three women approached me: the eldest had Sinatra at the Sands, attributed to my arrangement; her daughter cherished my album The Dude; and the youngest adored Thriller. Witnessing the emotional significance across generations moved me deeply.

What do you believe contributes to modern pop’s shortcomings?

Lack of formal training among musicians is a significant factor.

Aside from issues in song quality, are there fresh technical production methods switching things up?

No innovations exist currently; producers have grown both lazy and greedy.

How does this lack of effort manifest?

When you listen closely, it’s apparent that musicians are not honing their craft. Respect the gift you were given by mastering it.

Are your critiques of film scoring as harsh as your observations of pop?

Certainly, there’s not much merit found. The talent pool of composers seems overwhelmed with laziness. Alexandre Desplat stands out as an exception—he’s my brother.

When discussing the laziness of film composers, what specifically does that encompass?

It indicates they fail to appreciate the genius behind what Bernard Herrmann achieved.

What are your thoughts on the prospective future of the music industry?

The concept of a music industry has disintegrated! Had people paid heed to Shawn Fanning two decades ago, we’d be better. The industry is clogged with outdated financial minds. We need to rid ourselves of the “back in my day” mentality.

You’re venting frustration about the industry, but respectfully, could your views seem like “back in my day” complaints?

Musical principles endure, my friend. Today’s musicians can’t fully embrace their art as they lack foundational knowledge. Music embodies both emotion and science, and while emotion flows naturally, technique demands rigorous learning. Without mastering piano techniques, one’s ability to articulate musically is compromised. Musicians need broad exposure—are they knowledgeable of tango? Macumba? Yoruba music? Samba? Bossa nova? Salsa? Cha-cha?

Perhaps not cha-cha.

Marlon [Brando] used to cha-cha dance with us—effortlessly charming, he captivated everyone. He had a wild reputation. He’d hit on anyone, anywhere. Even the likes of James Baldwin, Richard Pryor, and Marvin Gaye.

Did he indeed? How do you ascertain that?

Come on, man. He never held back, no matter what!

What’s your familiarity with Brazilian music?

While I know Jorge Ben and Gilberto Gil, the musical epicenters belong to Gilberto and Caetano Veloso! I visit the favelas regularly; their struggles are immense. We may face hardships in America, but it’s even tougher there.

I understand you once carried a .32 for protection.

That’s correct.

Did you ever use it?

Yes.

At what target?

[[Grins.]Just for practice.

Shifting gears—a section of your memoir discusses—

Being a canine?

That wasn’t my line of thought, but I appreciate the perspective. I found a part of your memoir where you describe a breakdown after Thriller. You often highlight your triumphs—could you share about a notable struggle?

During the production of The Color Purple, Spielberg and I maintained a robust friendship—he’s a remarkable person. Yet, while others enjoyed vacations post-filming, I remained tasked with composing an extensive score. The pressure wore me out immensely.

What recent lesson have you taken to heart?

My last record [2010’s[2010’sQ: Soul Bossa Nostra]is a product of peer tribute where rappers wanted to pay homage to my legacy. I insisted their renditions outshine our originals, but that ambition fell short. T-Pain neglected integral details.

What positives emanate in your recent engagement with music?

Understanding its origins proves mesmerizing. During a previous trip with Paul Allen, I encountered a bathroom adorned with maps illustrating Earth’s appearance 1.5 million years ago. Combined, South Africa’s coastline was part of what today is considered China. These interactions likely shaped our music—the shared beat evident in both regions. African rhythms resonate even in Chinese melodies, as can be seen with their Kodo drumming. It’s a profound notion.

As your 85th birthday approaches, do you fear death?

No.

What are your beliefs regarding the afterlife?

You simply cease to exist.

Do you identify as religious?

No, man. My knowledge transcends faith. I was acquainted with Romano Mussolini, a gifted jazz pianist and Benito Mussolini’s son. We shared countless nights of music, wherein he recounted truths about the Catholic Church’s ethos. Its foundation seems driven by fear. Confession boils down to, “Reveal your sins, and all shall be pardoned.” That’s laughable. It’s curious that some of the world’s grandest structures are churches—it’s all about money.

On the topic of finances, allow me a blunt query: After spending your early years in jazz, an underappreciated genre, when did significant wealth become a reality?

Most momentum began post-Lesley Gore, which ushered me into the production realm. As the first black vice president at a record label [Mercury], my efforts initially went unpaid. Yet, in the ‘70s, as I stepped into producing and later teamed up with Michael, the cash flow surged. Furthermore, TV production— The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air andMad TV—provided substantial income, particularly through syndication.

How do your formative years—your upbringing and family issues—shape your view of success?

Totally impactful! My past fosters a deep appreciation for what I possess today.

What did growing up in a fractured family teach you?

Similar to the effects of poverty, man. I deeply value my current blessings.

How often do your thoughts return to your mother?

Consistently. She spent her final days in a mental institution. A truly brilliant individual who received inadequate help. Her mental illness could have been alleviated through vitamin B, but she couldn’t access it due to racial barriers.

When reflecting on her, what feelings emerge?

A longing for a deeper connection with her—as a child, that was a hard reality to accept.

What remains your most ambitious future project?

Qwest TV is generating excitement all around. It will serve as a musical equivalent to Netflix, showcasing unparalleled music from across genres worldwide. For any young listeners searching for exceptional content, it’ll be right at their fingertips. I’m astounded by my continued involvement in such initiatives. Having ceased drinking two years back has revitalized my creativity. I feel like I’m experiencing life anew. It’s been nothing short of extraordinary!

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

What does professional success mean to you

Ri=”www.vulture.com/_components/clay-paragraph/instances/cjdaoxyeu003m3b62mtc2b5dnw@published” data-word-count=”20″>How do you define success now?

Success is about fulfillment, not just wealth—it’s finding joy and purpose in my work and life.

Looking back, is there anything you would do differently in your career?

I might have taken more risks artistically. Often, I played it safe to maintain commercial viability, but I wish I had explored more avant-garde paths.