(Special writing on the occasion of Minto’s birthday)

In the literary history of Amritsar, ‘Shiraz’ Hotel had the same place as ‘Pak Tea House’ in Lahore. When you see, the circle of writers is frozen and topics from around the world are being discussed.

The splendor of ‘Shiraz’ was at its peak when the most popular poet of that era, Akhtar Shirani, came from Lahore. Along with Saifuddin Saif, Haji Laq Laq, Khalsh Kashmiri and others, a young Saadat Hasan was also a part of these gatherings along with his three other friends Hasan Abbas, Abu Saeed Qureshi and photographer Ashiq.

It was 1933 when a new face appeared in ‘Shiraz’ Ghulam Bari who used to write under the name of Bari Alig. He came from Lyallpur in connection with the job of ‘Masawat’.

Bari Alig is the person who shaped the young Saadat Hasan during the gatherings held in the same Shiraz Hotel, and made him the writer you and we know as Saadat Hasan Manto.

In the ‘Shiraz’ gatherings there were now three persons who were committed to equality, Haji Laq Laq, M Hasan Latifi and Bari Alig. The acquaintance made with Shiraz started to turn into friendship and now Manto along with his friends also started going to Equality Office. In the beginning, Bari Sahib used to get Manto to translate half a news, but very soon he started writing commentaries on films.

Minto first became a regular part of Equatorial and later got a job in Karamchand’s Lahore-based newspaper ‘Pars’ at Rs 40 per month. Within a short time he had to go to Kashmir due to illness from where he went to Amritsar instead of returning to Lahore. In the meantime, he sent some translations and typed material to the Bombay magazine ‘Masour’ which proved to be the first link in a new series.

First stop at Bombay

Inspired by Minto’s writings, Nazir Ludhianvi sent Minto to Bombay to edit his weekly magazine ‘Masoor’. Here also the same 40 rupees salary was fixed and Minto started writing critical articles and comments on films. Before this there was a vogue of large homoeopathic type commentaries. Minto created a storm with a series of columns like ‘Baal Ki Khal’ and ‘Nat Nai’.

According to Mirza Adeeb, ‘When he used to turn the pages of the painter, he would be surprised to see the skin of the hair and the page of Manto. Minto is such a fighter, he fights with everyone.’

Nazir Ludhianvi was very happy but Minto was finding it difficult to get by on Rs 40. Minto decided to try his luck in Bombay film studios.

First entry into the studio

Advertisements and reviews of V Shanta Ram’s film company Prabhat were published in Babu Rao Patel’s ‘Film India’, an English language paper. From there Minto got a small assignment of translation from English to Urdu. From here Minto bonded with Prabhat and got the opportunity to write dialogues for the film ‘Ban Ki Sundri’.

This was Minto’s first regular job in a studio, mentioning that he writes, ‘At that time I was employed by a film company on Rs 40 per month and my life was going smoothly. Wrote Chalu type dialogues for Chalu movie. Joked a little with the Bengali actress, who was called Bulbul-e-Bengal at that time, and flattered Dada Gore, the greatest film director of the era, and went home.’

Minto further writes that ‘the owner of the studio, Hormuzji Framji, a chubby, ruddy-cheeked Iranian, was in love with a middle-aged Khoja actress.’

After this film was completed, the search for new work began.

This section contains related reference points (Related Nodes field).

Imperial Film Company

After considerable shyness, Minto got a job at Imperial Film Company where he had to rewrite a few scenes from a script written by Hakeem Ahmed Shuja.

It was at Imperial that he got the chance to write ‘Kisan Kanya’. This was the first film for which the story, script, screenplay and dialogues were all written by Minto. In the process of making India’s first color film, Imperial imported heavy machinery, causing the company financial difficulties. According to Parvez Anjum, Kisan Kanya could not make any explosion at the box office, but it did not fail either.

This was followed by the release of his film ‘Meh Papi Kaho’ which flopped badly and took Imperial along with it. Minto’s next destination was Saroj Moi Tun.

Saroj Moy Toon

The company was founded in 1931 by Nanubhai Desai who was dying after giving famous films like Naqsh Soleimani, Roop Basant, Sassi Pannu, Mirza Sahiban, Sohni Mahiwal and Adal Jahangiri. Minto’s film ‘To Bada Kah Mein’ proved to be the last nail in the coffin and with its release in 1938, the company went bankrupt.

Seth Nanobhai Desai was not as stupid as the name suggests. He brought down another seth in the glass and set up a new company in the same four walls named ‘Hindustan Suntone’. A new story was written by Minto for the new company called ‘Mud’ meaning mud. The film was released in 1940 as ‘Apani Nagriya’ in Gujarati language and was a huge success.

Kisan Kanya was made in 1937, considered to be India’s first color film (Imperial Film Company).

Manto owed 1800 rupees to the company but she was being evasive. Minto, after making a lot of noise, took out barely five hundred rupees in cash and walked away.

After a few months of odd jobs in Bombay, he moved to Delhi Radio Station as a drama and feature writer in early 1941, where he stayed for about a year and wrote over a hundred plays.

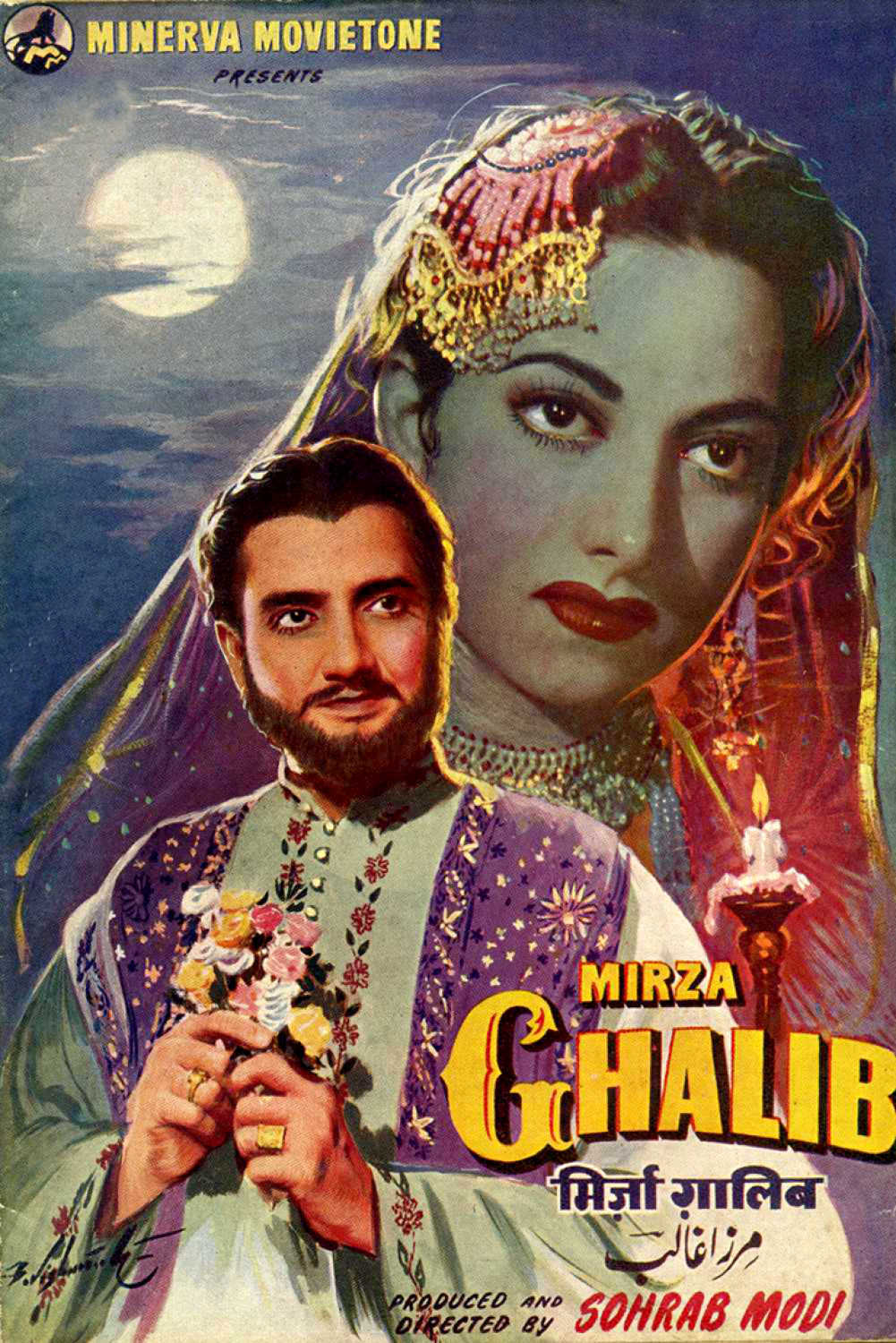

Delhi Radio Station and Mirza Ghalib Film

During his stay in Delhi, Manto’s engagements and nature varied but his association with the film somehow remained intact. An example of this is developing a story called ‘Banjara’ for a film with Krishnachandra. But the transfer of Mirza Ghalib’s story from Minto’s pen to the pages is the most memorable event of this period.

Manto writes in his essay on Mirza Ghalib, ‘Ghalib and the Fourteenth’, ‘These few pointers for the fiction writer can be of great help in charting the romantic life of Mirza Ghalib. The eternal triangle of the novel is completed by the short words of ‘Satam Posh Domni’ and ‘Kotwal Dushman Tha’.’

Much later, Sohrab Modi made this film, the script and dialogues of which were written by Rajendra Singh Bedi. Minto had a strong desire to go to Bombay for his exhibition, but his dream remained unfulfilled due to non-availability of a visa.

Another distinguishing feature of this film is Ghulam Mohammad’s fantastic music.

Return to Bombay and the role of Pagal in Eight Days

Minto never liked to interfere in his work. When he saw changes in his draft being forced in Delhi, he put his typewriter under his armpit and moved to Bombay.

On his return, he was keen to convert the artist into a monthly magazine based on Saqi’s impressions, but this bull did not materialise. He signed a deal with Sunrise Pictures to sell his film story ‘Nokar’ for 1250. The servant’s instructor was Syed Shaukat Hussain Rizvi.

Minto wrote songs with Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi but Rizvi did not like it. Later, the song was written by Nazim Panipati and Munshi Shams, whose lyrics were composed by Rafiq Ghaznavi.

After Naokar, Minto wrote Ghar Ki Shobha, Chal Chal Re Najang, Begum and Shikhari, but one of them, Aath Din, deserves a special mention for its historical significance. The film also starred Upendranath Ashok, Raja Mehdi Ali Khan and Manto in various roles.

The story of Mirza Ghalib is written by Manto while the dialogues are written by Rajinder Singh Bedi (Minerva Movietone).

During the eight-day shoot, according to Minto, one day my body dripped on from somewhere in strange clothes including body dirt. Minto offered Miraji to write two songs in order to get some financial support. Meera ji gave a standing ovation of non-filmy songs which were rejected.

Minto’s role in the film was that of a mad soldier, which was much talked about in the literary circles before the film’s release. According to Intizar Hussain, he saw this film in Meerut with Askari Sahib. As soon as Manto appeared as a mad soldier, he told me, ‘This actor is none other than Manto Sahib.’

Minto was quite excited after the release of this film. While mentioning in letters to friends, they also mention the golden dreams of the future. But in the meantime, the partition was broken and everything fell apart. However, the image of Bombay could not be dimmed by Minto’s life.

In Bombay there were parties of friends and frolics, there were silly sets and ‘hip-talla’ girls, and above all there was an abundance of alcohol. Crazy people and colorful wines, what else could Minto need? After coming to Pakistan, Manto remembered this period till the end.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘2494823637234887’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

#Minto #worked #Bollywood #ten #years

here, and I had to go to the bathroom. It was embarrassing because I was supposed to be more composed as a writer. But amidst the chaos and discomfort, I managed to focus on my work. The production was hectic, but I found joy in the creative process, collaborating with various artists and actors.

As the film progressed, I often reflected on the journey that had brought me back to Bombay, to the heart of the film industry that both excited and overwhelmed me. With the hustle of filmmaking around me, I delved into writing with renewed vigor, pouring my thoughts and experiences into the screenplays and dialogues I was entrusted with.

Later Years

Despite the successes and challenges, my relationship with the film industry continued to evolve. I faced multiple setbacks, including financial difficulties and creative disagreements, but I persevered. Each project taught me something new, and with every script I wrote, I felt myself growing as a storyteller.

In retrospect, my journey through the world of cinema was more than just a career; it was a canvas where I painted my thoughts, struggles, and aspirations. Whether through the poetics of dialogue or the profoundness of character development, I aimed to capture the essence of human experience and emotion in my work.

As I look back on my experiences in filmmaking, I’m reminded of the beauty of collaboration and the richness that different perspectives bring to the art. Though I may not have achieved every dream I set out for, the journey itself, filled with creativity and expression, has been profoundly fulfilling.

And as I navigate the ever-changing landscape of cinema, I carry with me the lessons learned and the stories left to be told—all part of a legacy that continues to inspire and resonate.