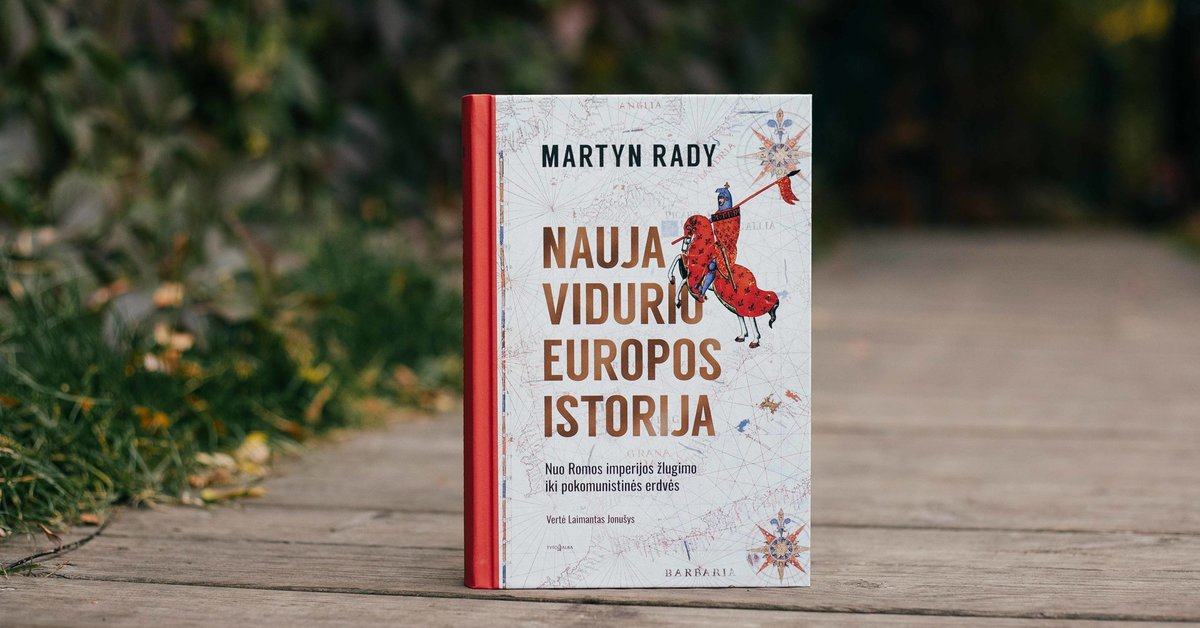

These are some interesting facts from the recently published Lithuanian book of the British historian Martyn Rady “New Central European History”, which was translated into Lithuanian by Laimantas Jonušys.

This book is certainly not a collection of exotic or sound facts, but an interesting and intriguingly told story of Europe. Considerable attention is paid to Lithuania and the time when our country was an important and influential player on the European political map.

A New History of Central Europe helps to better understand how Europe became what it is today. And why do they face one or another challenges.

In this excerpt from the book, the reader will travel to the time when the face of the continent changed irreversibly – the entire large state was swept away, according to M. Rady, the great orangutan of Europe – the Republic of the Two Nations.

***

The United Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania did not survive. 18th century Central European governments have greatly increased their military and bureaucracy. Disciplined the aristocracy by forcing them into civil service, suppressed assemblies and removed many obstacles to effective governance.

Almost everywhere, laws were made by edict, not by agreement with the privileged classes. The French philosopher Montesquieu (1689-1755) saw this clearly. According to him, the “mediating forces” that restrained power and supported the spirit of freedom were overthrown or weakened everywhere in Europe. Without the countervailing political power of the nobility, city magistrates, and clergy, monarchical despotism flourished.

Montesquieu saw an exception in Poland-Lithuania. The United State had preserved the historical constitution brought back from the Middle Ages – it even allowed “a clear idea of the Europe of the past”. Montesquieu described it mainly in terms of agricultural conditions and the oppression of serfs by landlords, but (as Montesquieu also suggested) its institutions were also echoes of the past. Poland-Lithuania stood out in Central Europe because the nobility was still powerful here. During the 15th and 16th centuries the acquired privileges not only remained intact, but also expanded. As well as the powers of the nobility-dominated Seimas. As its representatives liked to explain, they live in a “democracy of the nobility” and have been so for centuries.

Poland-Lithuania stood out in Central Europe because the nobility was still powerful here.

Even in the 16th century In the 1970s, the Seimas gained great powers through the Articles of Henry, allowing them to control a large area of politics and decide who would be the monarch by election. Electoral seimas, which were often attended by tens of thousands of nobles, in the 17th and 18th centuries. was still a feature of Polish and Lithuanian politics. When the nobles gathered en masse to elect a ruler, their representatives set out new conditions obliging the winning candidate to provide scholarships from his own pocket so that the sons of the nobles could study abroad, repair border forts, pay for the Baltic fleet, and so on. And yet, the Seimas constantly feared that the monarch would introduce autocratic rule by using the remaining powers. Therefore, they restricted the power of the ruler – they took away taxes, the army and the ability to conduct foreign policy through permanent ambassadors in other countries.

However, after depriving the king of his powers, the Seimas itself proved to be incapable of managing those powers. Seimas procedures constantly turned into a loose puddle. The worst thing is that any single deputy could cancel legislation passed by the Seimas using the right of veto, usually by shouting “Nie pozwalam!” (“I don’t allow it!”) in the hall. In fact, he didn’t even have to attend – all he had to do was register his protest in writing.

From the first veto in 1652 until the end of independent Poland-Lithuania in 1795 two-thirds of Seimas meetings collapsed either due to a veto by some deputy or parliamentary obstruction, when a group of deputies gave speeches one after another for days and thus blocked the adoption of laws. The same thing happened in the provincial seimes – there the deputies used the right of veto just as often and enthusiastically.

From the first veto in 1652 until the end of independent Poland-Lithuania in 1795 two-thirds of Seimas meetings failed either due to a veto by a deputy or due to parliamentary obstruction.

Liberum veto (free “ban”) was exalted by the Polish and Lithuanian nobility as the embodiment of freedom. 18th century the author of the popular treatise written at the beginning explained: “The right of veto is a special feature of the Polish nobility and a pillar of its freedom, – and continued to say: – If it was removed, freedom would be destroyed, and the rights of the nobility would be compared to the rights of the nobility of other countries, living under conditions of absolute power.”

It’s not completely absurd. The ruler still had broad powers of patronage and could count on the support of the nobles, appointing them to lucrative posts, gifts of royal lands and, perhaps most importantly, attractive positions in the Church, since the monarch had the right of appointment in it. Many nobles feared that an unscrupulous ruler could buy the majority of the Seimas. In their understanding, the right of veto was a brake that allowed a single honest deputy to stand in the way of a Seimas bribed and manipulated by a treacherous monarch.

Foreign observers were confused by Polish-Lithuanian politics. The opinion of many was summed up by a French traveler: “Polish government, its constitution, the way elections are conducted and meetings are managed, everything is so absurd that the country will not survive.” Yet it miraculously held on.

Oddly enough, after 1772 The two decades after the partition were a golden age for the remaining Poland-Lithuania. Literature, art, theater and education flourished. More than two hundred artists worked in Warsaw, of which seventy were closely connected with the royal court. In the countryside, wealthy landowners rebuilt their palaces in the fashionable Palladian style with pilastered porticos, modeled on English mansions. Although King Stanislaus Poniatowski was a puppet and reported to Catherine II, he turned out to be an enlightened and thoughtful sovereign. He advocated university reform and sponsored the first Polish newspaper, the Monitor (1765–1785). The twice-weekly issues dealt with superstition, religious fanaticism and, as it was described, the new Polish passion for gossip and duels.

Oddly enough, after 1772 The two decades after the partition were a golden age for the remaining Poland-Lithuania.

King Stanislaus built on flimsy foundations. Even in the 18th century in the 1950s, a Polish scholar set out to compete with Chamber’s new encyclopedia and claim Diderot’s seventeen-volume Encyclopédie by publishing his own collection of knowledge, the New Athens. Here the existence of giants and unicorns was affirmed, but the pelicans were called a hoax and the Copernican universe a lie. In that encyclopedia, the horse was defined in a bewilderingly simple way: “a horse: as it is, for all to see.” But from the 18th century the diminished kingdom of the seventies was influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment and destroyed many of the assumptions and pretensions and much of the presumptuous ignorance that had previously governed its politics and led to its catastrophe. Partly influenced by the example of King Stanislaus, the influential Polish-Lithuanian nobility finally recognized the country’s political, social, cultural and economic backwardness and decided that something had to be done.

All of Central Europe was under the spell of Montesquieu. In Poland-Lithuania, the reformers wholeheartedly accepted Montesquieu’s ideas. From 1788 to 1792 the new Seimas met more than 560 times, and during that period the right of veto was withheld. There were many talks – no less than thirty-two thousand speeches and speeches. But King Stanislaus accelerated things – he wrote a constitution and in 1791 May 3 pushed it through the Seimas, on this occasion it was crowded with his supporters. And after all, he presented the purest Montesquieu to the Seimas, fully applying the principle of separation of powers.

The May 3rd Constitution is hailed as the first modern constitution in European history and the second in the world (after the 1789 Constitution of the United States). However, it was not as revolutionary as Stanislaus and his supporters claimed. In addition to Montesquieu, Seimas deputies praised his Genevan rival Jean-Jacques Rousseau and talked about the constitution giving power to the nation and conveying its will.

Although the Constitution refers to peasants and not serfs, the institution of peasant enslavement was not abolished.

However, in 1791 the “Polish nation” was still the nobility, and, by the way, only its wealthy members, because the Constitution deprived the poorer people of the right to vote for the deputies of the Seimas. Although the Constitution refers to peasants and not serfs, the institution of peasant enslavement was not abolished. And although religious tolerance was approved, the Constitution considered conversion from Catholicism a crime for which unspecified punishments threatened. To prevent foreign manipulation in the election of the king, the monarchy was declared hereditary, but there was no thought of introducing the institution of the presidency or the rights of citizens.

King Stanislaus rejoiced at his victory. Believing that the Constitution changed the perspectives of Poland-Lithuania, he predicted that “those eyes that see Poland today will not recognize it when they see it thirty years from now”. Stanislaus was right, but in such a tragic sense that he had not imagined.

#book #British #historian #close #Lithuania #exclusive #liberum #veto #Culture