A recent study has revealed that patients with preexisting parasympathetic predominance tend to experience ongoing heart rate reductions following the commencement of fingolimod (Gilenya; Novartis) treatment for relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS).

This significant research was published in the esteemed journal Clinical Autonomic Research.1

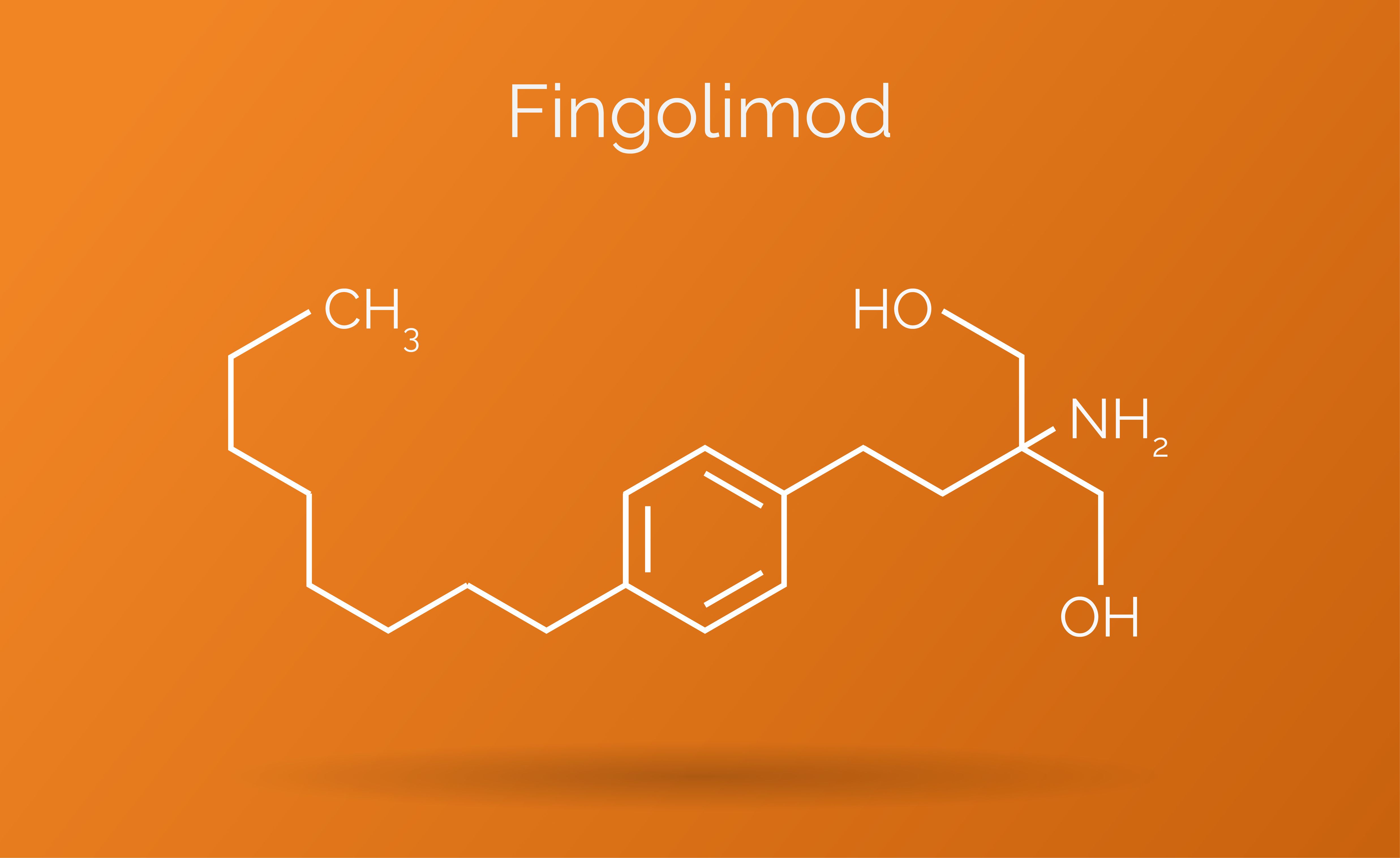

Fingolimod is known for causing a temporary dip in heart rate and blood pressure due to its vagomimetic and vasodilatory properties as an S1P receptor modulator. Authors have indicated that this therapy can typically lead to a heart rate decrease of 10 to 15 beats per minute, though this effect generally resolves within 24 hours.

“Negative chronotropic and dromotropic effects of fingolimod are typically transient, arising upon initiation or reinitiation of the therapy after a break, presumably because the agonistic effects of fingolimod on S1P1 receptors diminish while desensitization and internalization of these receptors begin several hours after treatment starts,” the authors explained.

Remarkably, a subset of patients continues to experience heart rate deceleration even months after beginning the fingolimod regimen, potentially due to underlying autonomic dysfunction, according to the research team. A 2014 study highlighted a significant relationship between measures of parasympathetic function and the occurrence of bradycardia in the initial six hours following therapy initiation.2

The authors noted that sinus bradycardia following fingolimod initiation links to heightened parasympathetic activity, while bradyarrhythmia is associated with diminished sympathetic function. However, they sought to investigate whether existing central autonomic dysfunction often seen with MS may contribute to lasting heart rate reductions or persistent changes in autonomic response, enduring well beyond the onset of treatment.

To delve deeper, the research team enlisted 34 patients diagnosed with RRMS, monitoring their RR intervals and blood pressures both at rest and during posture changes prior to fingolimod treatment. Subsequent evaluations were conducted after treatment at intervals of 6 hours and 6 months.

At the 6-hour mark, all participants showed an uptick in heart rates alongside increases in key measurements like RR intervals, root mean square of the successive differences (RMSSDs), and baroreflex sensitivity (BRS).

Notably, among the 34 patients studied, 11 individuals exhibited prolonged bradycardia. Prior to initiating treatment with fingolimod, these 11 patients showed no reduction in parasympathetic RMSSDs and high-frequency powers upon standing.

“After 6 months, while all measured parameters had largely returned toward pretreatment levels, the 11 patients with ongoing heart rate deceleration maintained lower heart rates compared to their baseline, whereas the remaining 23 participants had diminished parasympathetic RMSSDs and baroreflex sensitivity compared to their pre-treatment metrics,” the authors reported.

Their findings bolster the hypothesis that both the immediate heart rate deceleration post-treatment initiation and the longer-term, six-month persistent deceleration are closely linked to preexisting alterations in central autonomic mechanisms.

“This study may be the first to demonstrate that patients with RRMS who experience enduring heart rate slowing during prolonged fingolimod therapy have an underlying autonomic dysfunction that is not evident in patients who recover their heart rates promptly after treatment begins,” they elaborated.

The researchers emphasized that while the clinical manifestations in the 11 patients with extended heart rate slowing were minimal, there were no observed significant autonomic dysfunction or cardiac issues resulting from this observation. “After 6 months, there had been no clinically significant autonomic dysfunction or cardiac complications arising from the treatment,” they noted. “Nonetheless, conducting autonomic evaluations for patients with MS can be invaluable to identify those exhibiting central autonomic dysfunction prior to disease-modifying therapies, thereby assessing any possible increased cardiovascular risks associated with S1P receptor modulators.”

They concluded by advocating for further research to explore other factors potentially linked to cardiovascular risks in patients on S1P receptor modulators.

References

1. Hilz MJ, Canavese F, de Rojas-Leal C, Lee DH, Linker RA, Wang R. Pre-existing parasympathetic dominance seems to cause persistent heart rate slowing after 6 months of fingolimod treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Auton Res. Published online October 9, 2024. doi:10.1007/s10286-024-01073-w

2. Rossi S, Rocchi C, Studer V, et al. The autonomic balance predicts cardiac responses after the first dose of fingolimod. Mult Scler. 2015;21(2):206-216. doi:10.1177/1352458514538885

The Heartbeat Enigma: Fingolimod and those Persevering Patients

Greetings, dear readers! Put down that cup of tea and pay attention. Today, we dive into a medical phenomenon that sounds like it fell straight from the pages of a sci-fi novel but is all too real: the curious case of fingolimod and its troublesome effect on the hearts of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. You could say it’s a story of love… and bradycardia. Let’s put on our comedy hats and dissect this like a skilled surgeon—minus the blood, of course!

What’s the Big Deal with Fingolimod?

Fingolimod, marketed as Gilenya, is a medication aimed at tackling the annoyances of relapsing/remitting MS (sounds like a bad romantic comedy, doesn’t it?). However, it comes with a side effect that resembles an accidental heart-to-heart incident after a few too many at the pub—a sudden slowing of the heart rate.

Now, according to a study published in Clinical Autonomic Research, this isn’t just a minor hiccup but a persistent situation for some. Imagine having a heart rate so low it could be mistaken for a moody teenager on a lazy Sunday! The study reveals that patients with preexisting parasympathetic predominance may bear this burden long after the medication kicks in.

The Science of Slow Heart Rates

You see, when patients begin their fingolimod journey, their heart rates take a little vacation—experiencing a drop of about 10 to 15 beats per minute. Typically, this brief respite lasts a mere 24 hours, but not for everyone. A peculiar subset, alas, seems to carry this sluggishness like a badge of honor for months on end. Yes, it’s what you might call a persistent party crasher of the cardiovascular kind.

The authors of the study went to great lengths—tracking 34 patients meticulously pre- and post-fingolimod—like detectives on the trail of sluggish synapses. What did they find? A motley crew of heart rates and rhythm intervals, with some sad souls—11 to be exact—falling into a prolonged state of bradycardia. It’s like finding out you’re the only one who forgot to wear pants at a party. Not comforting!

The Autonomic Dysfunction: A Heart of Gold… or Lead?

Apparently, those lingering heart issues correlate with preexisting autonomic dysfunction—a fancy term that means their bodies’ automatic systems are perhaps a wee bit confused. These poor patients may have been cruising along with elevated parasympathetic activity before they even said, “Yes, I’ll take the fingolimod.” So, when they signed up for the treatment, they weren’t equipped with the best cardiovascular tools for the job. Talk about being set up for a fall! Or should we say, a slow fall?

Minor Trouble or Major Mess?

But wait! Before you gather your family and friends for an intervention, the findings revealed that despite this uninvited heart rate slowdown, the clinical impacts were surprisingly minor. It’s like finding out that those embarrassing Facebook photos from college had no lasting effects on your life… at least not until your mom comments on them! The study noted no major autonomic dysfunction or cardiac complications for the 11 patients struggling with persistent bradycardia.

What’s Next? More Questions than Answers!

While it’s all relatively tame on the clinical outcome front, the authors recommend more research to delve into whether other factors could affect cardiovascular risk while taking S1P receptor modulators like fingolimod. Because honestly, who doesn’t love a good mystery?

Conclusion: A Cautionary Tale

In summary, if you’re one of the unfortunate souls who’s caught in the prolonged heart rate slow lane, know that you’re not alone. Researchers are keeping an eye on the situation, and if we’ve learned anything today, it’s that knowledge is power (not to mention hilarious). So, let’s raise a glass—not too high, don’t want to strain that heart rate—and appreciate the quirky complexities of medical treatment and the human body. Cheers!

Feel free to adjust any section as needed; this is designed to capture the comedic yet informative essence you requested!

Sympathetic activity even before starting treatment. To shed light on these intriguing findings, we have Dr. Maria Hilz, the lead author of the study published in Clinical Autonomic Research. Welcome, Dr. Hilz!

Editor: Thank you for joining us today, Dr. Hilz. Your study presents some fascinating insights into the effects of fingolimod in patients with relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. Can you summarize the key findings for our readers?

Dr. Hilz: Certainly! Our study highlights that while fingolimod is known to cause a temporary decrease in heart rate shortly after treatment initiation, a subset of patients—specifically those with preexisting parasympathetic predominance—tends to experience ongoing heart rate reductions that can linger for months.

Editor: That’s striking! What do you believe is the underlying cause of this persistent bradycardia in certain patients?

Dr. Hilz: The prolonged heart rate slowing appears to be linked to existing autonomic dysfunction that many patients with MS may have. Essentially, this dysfunction can affect how the body responds to medications like fingolimod, leading to atypical cardiovascular reactions that persist even after the initial effects wear off.

Editor: You mentioned monitoring 34 patients during the study. What were some of the notable observations from the data collected?

Dr. Hilz: Yes, we closely tracked their heart rates and other autonomic measures both before and after starting fingolimod. While most patients returned to baseline levels within six months, we found that 11 individuals continued to demonstrate lower heart rates. They also showed little to no improvement in certain parasympathetic measures, indicating a deeper, unresolved autonomic issue.

Editor: That’s quite important for both clinicians and patients to understand. Were there any significant clinical implications for those experiencing this ongoing heart rate issue?

Dr. Hilz: Fortunately, there were no major adverse effects or clinically significant cardiac complications in these patients during our study period. However, it emphasizes the necessity of conducting thorough autonomic evaluations before starting treatments like fingolimod. Identifying patients with underlying dysfunction could help in managing and predicting potential cardiovascular risks.

Editor: It seems there’s a call for further research in this field. What future studies do you envision could build on your findings?

Dr. Hilz: Absolutely. We believe it’s vital to further explore the relationship between autonomic dysfunction and cardiovascular responses to S1P receptor modulators. Additionally, examining other factors that may affect cardiovascular health in MS patients could lead to more tailored treatment approaches.

Editor: Thank you, Dr. Hilz, for sharing these enlightening insights and shedding light on this intriguing aspect of fingolimod treatment. We appreciate your efforts in advancing our understanding of its effects on heart health in MS patients.

Dr. Hilz: Thank you for having me! It was a pleasure discussing our work and its implications for patient care.

Editor: And thank you to our readers for tuning in! We hope this interview provides a clearer picture of the surprising effects of fingolimod treatment and encourages further discussion on the topic. Stay informed and take care!

Ity of conducting thorough autonomic evaluations prior to starting therapies like fingolimod, especially in MS patients. Understanding a patient’s autonomic status can help pinpoint those at risk for persistent cardiovascular effects, which might inform monitoring strategies moving forward.

Editor: That’s a very valid point. Your study certainly opens the door for future research. What direction do you see this field heading in, particularly regarding fingolimod or other S1P receptor modulators?

Dr. Hilz: We encourage further investigations into the mechanisms behind these autonomic changes and whether other factors, such as concurrent medications or individual patient characteristics, might influence cardiovascular outcomes. Additionally, exploring the interactions between MS disease progression and autonomic functioning could provide deeper insights into the best management practices for patients on these therapies.

Editor: Thank you, Dr. Hilz, for sharing your captivating findings and insights. It appears that continued research will be vital in ensuring the best possible outcomes for patients undergoing treatment for multiple sclerosis—and perhaps shedding light on some of the comedic complexities of the human body along the way!

Dr. Hilz: Absolutely, and thank you for having me! Let’s keep the dialogue going as we unravel these intriguing medical mysteries together.

Editor: And thank you to our readers for joining us on this journey through the fascinating interplay of medications and our autonomous systems. Stay tuned for more updates in the world of health and medicine!