Edgar Arias is one of the most recognized journalists in Valle del Cauca. 33 years ago he joined Noti5, the news program where he worked as a reporter, correspondent, editor-in-chief and general editor until he became director of the weekly newscast broadcast on Telepacífico.

According to the criteria of

Thanks to television, he has covered the most important situations in Colombia and the world, having access to some of the most representative characters of the time. The interview is his favorite format. It seduces him to the point of studying figures from the most varied fields and not allowing them to escape him, no matter how elusive they may be. “When they tell me that they don’t give interviews, my mouth waters,” points out.

Share

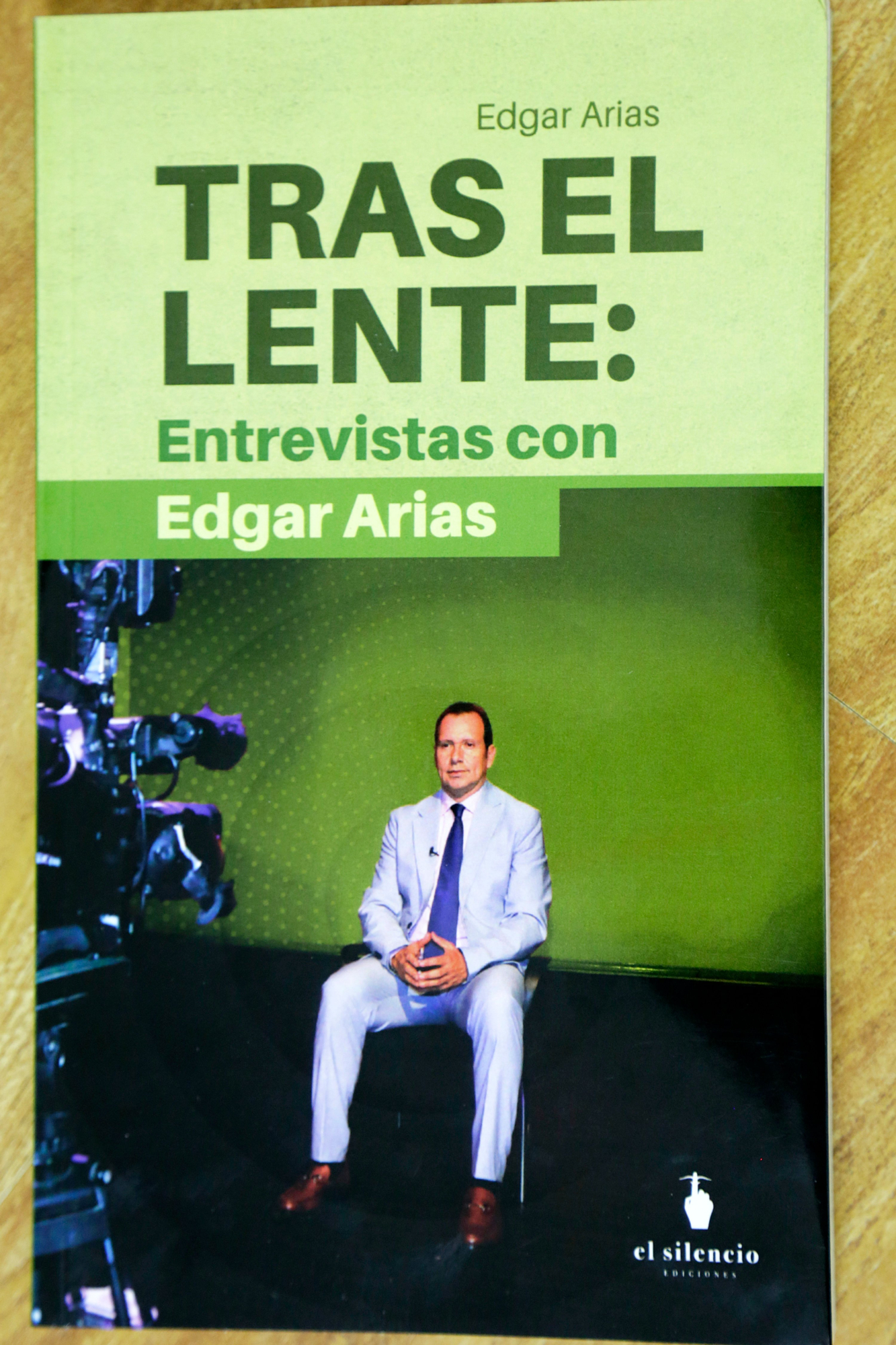

Behind the lens: Interviews with Edgar Arias was presented during the Oiga Mire Lea International Festival, in Cali.

Photo:CEET/ JUAN PABLO RUEDA

He recently made the decision to take his recordings out of the drawer and transcribe them, perhaps persuaded by an idea that Fernando Botero told him in 2013: “If you paint a work and save it, it does not exist, because it has to exist in the mind of the viewer.”

Arias has just published ‘Tras ellen’, the book that brings together her talks with political figures such as Michelle Bachelet and Mariano Rajoy; from sports like Pelé and Falcao; and the artistic like Fernando Botero, Juana Acosta and Deepak Chopra, among others.

The launch of the book was during the Oiga Mire Lea International Literature Festival.

In the prologue of her book, Claudia Palacios talks about the privilege of being a journalist, how does she perceive that?

It is a plus to have national and international figures face to face. That is why you have to prepare to take on that challenge. Because it is a unique opportunity and we must take advantage of it. And to take advantage of it one must prepare. I was always concerned that these people felt, not only comfortable, but that they had the time and ease to tell their profile and their human characterization.

That human part becomes the focus of your interviews, why?

The human part becomes the main focus because people do not know what is behind that face, behind that body, behind that character. I was always concerned about researching people thoroughly so that they felt comfortable. And so it continues to happen. That is to say, when I approach a character he realizes that I know him very well and little by little he goes, not from a trick question, not from a rushed question, to a moment in which that person is comfortable and in In that instance you can get to much deeper topics without violating that person’s privacy. I was recently interviewing Gilberto Santa Rosa and the guy told me that I had gotten him into the ranch because I knew things about him that no one knew, like that he had started his career doing imitations. But I had found out that a long time ago when I interviewed Víctor Manuelle and he told me the anecdote.

How do you investigate characters who stand out in such different fields?

Sometimes journalists are very involved in the issues of journalist groups. Because it happens that there is a forest fire, someone has been killed, there is a march or there are possibilities of rationing and that is important, but I think we have lost a lot of that essence of knowing these characters to be able to address them. In this sense, It was not in vain that I read 5 or 6 books by Maestro Botero and Deepak Chopra to be able to interview them. It’s not the question that everyone asks: how do you feel?, and what is the next step?, and what is the purpose…? I think that the open question already generates distrust for the interviewee because it is more of the same.

When you have a character so well studied, how do you decide between what you want to ask and what audiences should know?

It is not good to have interviews so scripted. You usually make that mistake in the first interviews you do because you have 20 minutes and you have to touch on those topics you prepared. But by having more room, you analyze what they are telling you to make the conversation richer and you already know that the reader or viewer will be interested. You have to know how to listen to do a good interview.

When does a journalist make a mistake doing an interview?

We make a mistake as journalists when we think that we are going to cork and that we are going to ask the character something that is going to make him look bad. When we think that we are going to impose ourselves and have the seat higher than the interviewee. We lose there because people really want to listen to that character. One has to be the tool and the vehicle to get him to say what the reader wants to know. Why was Falcao a scorer? Why did Orlando Duque jump from 18, 25, 30 meters high and what is he afraid of? Knowing that this man jumps from 30 meters into the water but is afraid of spiders…

You spent an evening with Botero in Tuscany (Italy) and when they brought two wines you still didn’t know if you were going to be able to interview him, what were you thinking at that moment?

I had the attention defined but not the interview. Sophia (Vari), his wife, tells me: “Be careful, he drinks the third wine and is already talking about his topics, so he has to complete the interview.” Obviously I was more concerned than anyone that he had his second wine and I told him with great regret that I had flown to Italy to be able to interview him. He told me he had sixty minutes and that’s when I told him that an established artist like him has everything planned and his response was: “You’re wrong. I am just learning to paint at 82 years old.”

In the book he mentions that some interviewees may be alien to younger readers; However, many figures remain in memory for works like this. Who did you meet thanks to the interviews?

Of course, work like this achieves that. It happened to me with Gabriel García Márquez, whom I was never able to interview, and that’s how I found out things about how he moved, how he spoke, what his reaction was when he was criticized for his ideology… So in some way interviews immortalize people. At some point I thought about leaving out the people who had died from the book, believing that it had no significance, but then I thought that it was the opposite, because that is how these people can be known.

This book has the particularity of including notes and, in many cases, the story of how the interviews were obtained. Did you always have it in mind that way?

It was planned. Something more had to be done with those interviews, because television is only a means of communication and sometimes time is not as generous with that format as it is with a book or a magazine. I thought about not being selfish because the only place to store things is the trunk or the nightstand and suddenly many journalism students are going to find a tool here.

Were there any interviews that you couldn’t include in the book?

It happens that the visit of one of the survivors of the accident in the Andes, which inspired the film ‘The Snow Society’, was postponed, it is something on the calendar. The same Gilberto Santa Rosa, but I interviewed him fifteen days ago. There will always be a next interview but I had to get the book out and I think the selection is varied and I am satisfied.

With all the changes that journalism is having towards the digital format, you decide to opt for a book of interviews, why?

The opportunity is there and the competition is with content. It’s very good to take out the headline, think about the ‘likes’, the followers, but I think that the competition, sooner rather than later, will be with content. Because the digital rush is leading us to people only paying attention to our three or four minute texts and I think that In the end, the fundamental ingredient of the complete text will prevail. When there is information and context, people are going to look there and read again.

JUAN JOSÉ RÍOS ARBELÁEZ

School of Multimedia Journalism EL TIEMPO