A recent study conducted with a small group of United States veterans and published in the Journal of Affective Disorders suggests that creatine levels in a specific region of the brain might play a significant role in recovering from traumatic events. This study provides preliminary evidence that higher levels of creatine are associated with better recovery from stress caused by traumatic experiences.

The focus of the study was to understand why some individuals recover from traumatic events while others develop long-lasting psychological conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Traditional research has primarily focused on psychological and environmental factors contributing to PTSD, but there is an increasing interest in exploring the biological and neurochemical underpinnings that may predispose individuals to or protect them from the long-term consequences of trauma.

PTSD is a mental health condition that can develop following a person has experienced or witnessed a traumatic event. It involves intense and disturbing thoughts and feelings related to the traumatic experience, which persist long following the event has ended. Symptoms of PTSD include flashbacks, nightmares, heightened emotions, and a sense of detachment from others. These symptoms significantly disrupt daily functioning and are categorized into re-experiencing the trauma, avoidance of trauma reminders, negative changes in thoughts and mood, and alterations in physical and emotional reactions.

In this study, researchers focused on creatine, an organic compound crucial for energy production in cells. It is primarily found in muscle and brain tissues, where it aids in maintaining energy supply. Creatine enables the regeneration of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the primary energy carrier within cells, which is vital for maintaining cellular function and integrity.

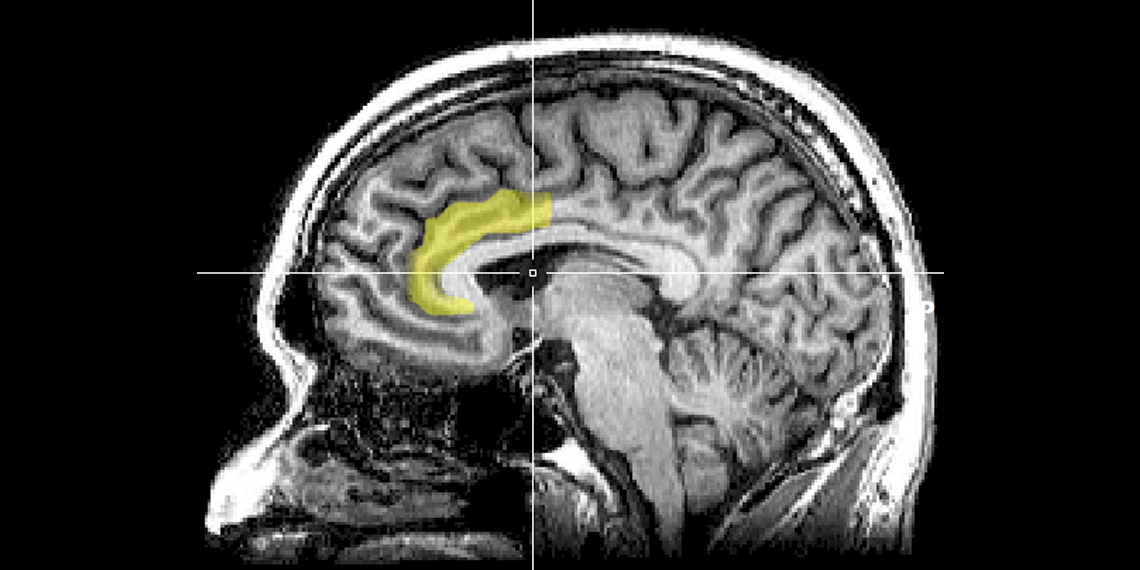

Based on their hypothesis that creatine levels in the brain might influence an individual’s ability to recover from trauma by affecting energy availability in critical brain regions, the researchers conducted brain scans on a group of 25 U.S. veterans recruited from the Intermountain West region. The scans specifically measured the concentration of creatine in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region associated with emotional regulation and response to stress.

The findings of the study revealed that veterans with higher levels of creatine in the ACC reported greater reductions in stress over time since their most traumatic event. This indicates a potential role for creatine in the brain’s ability to recover from trauma.

Interestingly, the study did not find significant relationships between creatine levels and the number of traumatic events experienced or the current severity of PTSD symptoms. This suggests that while creatine may influence the recovery process following trauma, it is not necessarily correlated with the initial response to trauma or the ongoing severity of PTSD symptoms.

The study also examined whether creatine levels differed between individuals on medications, such as antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs, and those who were not. The researchers found no significant differences in creatine levels based on medication use, suggesting that the observed effects of creatine on stress recovery were not confounded by these medications.

While this study provides compelling preliminary evidence, it is worth noting its limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and the participants were predominantly male veterans. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Additionally, the study relied on participants’ retrospective reports of stress levels, which might introduce bias.

Future research should aim to include larger and more diverse populations, employing longitudinal studies to track changes in creatine levels over time following traumatic events. Expanding the research to clinical samples with more severe PTSD symptoms might also provide deeper insights into the role of creatine in mental health outcomes following exposure to traumatic events.

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential association between creatine levels in the brain and the recovery process from traumatic events. Although further research is needed to confirm and expand upon these findings, the implications are significant. Understanding the neurochemical underpinnings of trauma recovery might potentially lead to the development of new interventions and treatment options for individuals experiencing mental health conditions related to traumatic experiences.

As society becomes more aware of the impact of trauma on mental health, it is crucial to continue exploring these biological and neurochemical factors. By unraveling the intricate mechanisms involved in trauma recovery, we can better support and assist those who have experienced traumatic events. The potential future trends in this field include personalized treatments targeting creatine levels and energy regulation in the brain, as well as the integration of innovative neuroimaging techniques to enhance our understanding of trauma and its effects on the brain.