2024-05-02 03:45:06

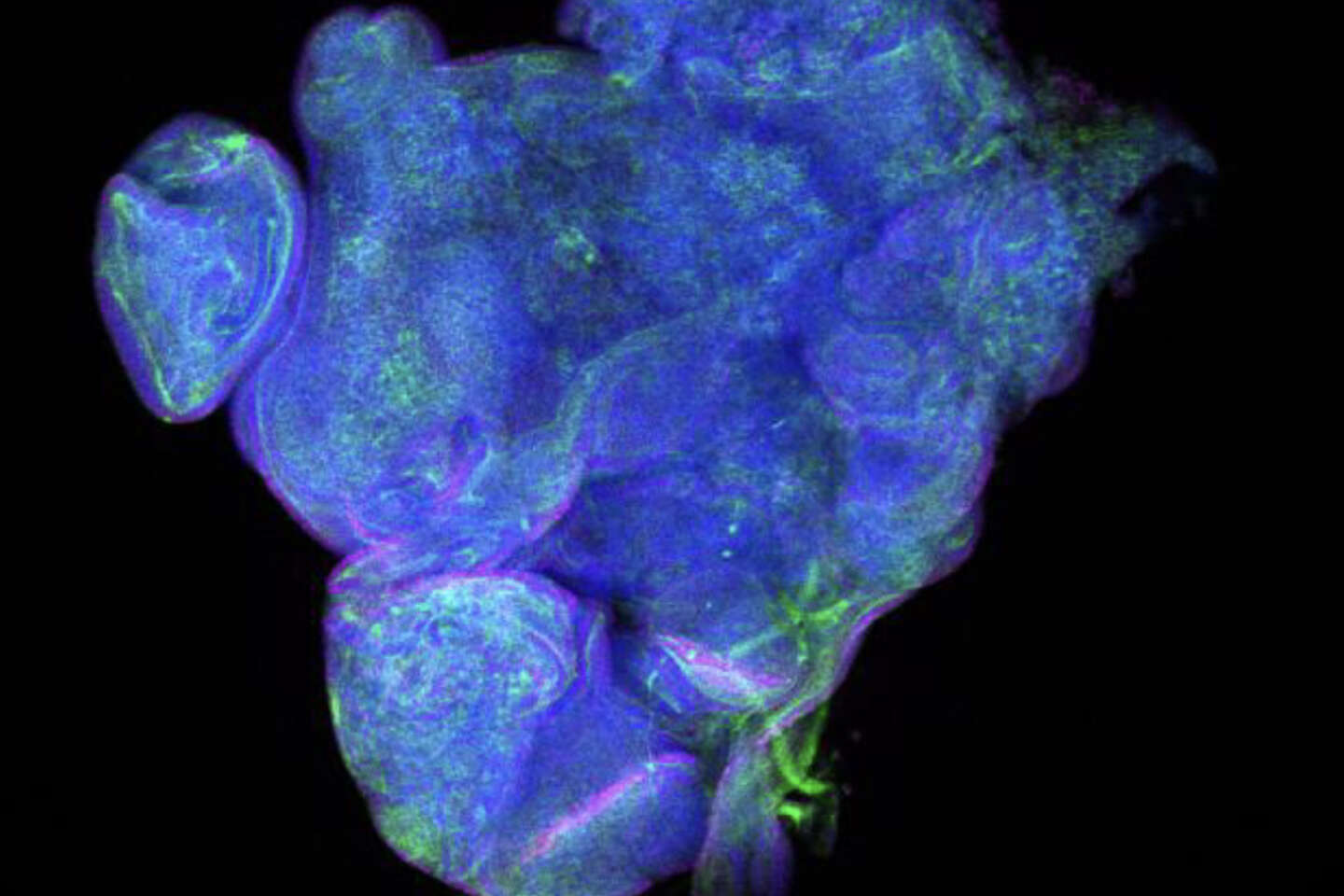

A tumor, a cluster of abnormal cells, caused by an epigenetic disruption. The DNA, colored blue, is no different from that of a healthy cell. GIACOMO CAVALLI / CNRS

This might be the missing piece of a thirty-year-old theory. Since the end of the 1990s and the genetics revolution, the origin of cancers has been commonly accepted: the accumulation of mutations in DNA leads to disruption of certain key genes and the disturbed cells begin to proliferate until they form a mass of abnormal cells: a tumor. However, this theory does not seem to apply to certain cases. “There have been some doubts, particularly in the last decade, since, in certain cancers, we have not really found a mutation”explains Giacomo Cavalli, CNRS research director at the Institute of Human Genetics, in Montpellier.

But how can cancer occur without a mutation in the DNA? Epigenetics may well be the answer. A term that may seem barbaric. Epigenetics is the study of the mechanisms that mean that the same DNA sequence can be expressed or not, depending on the context. This helps to explain why the human body is made up of very different cells (neurons, muscle cells, etc.) which nevertheless have an identical genome.

Several previous studies have highlighted the important role of epigenetics in cancer. “But epigenetics always intervened secondarily: first, there were mutations, and these mutations led to epigenetic deregulations which contributed to the proliferation of cancer cells”, specifies Giacomo Cavalli. It was enough for this Montpellier researcher and his team to try to prove that it was possible to cause cancer simply by causing a transient disruption of certain genes.

Vinegar Flies Experiments

“We have shown that we can get cancer without there being any DNA mutations”he sums up today. Their show of force earned them a publication in the British magazine NatureWednesday April 24.

How did they do it? They inactivated the gene Polycomb for just twenty-four hours using biomolecular technology. However, this gene prevented cancer, in particular by preventing cells from proliferating. And when, following twenty-four hours, the gene returned to its normal expression level, it was already too late. The cell had begun to go haywire, multiplying uncontrollably, forming a clump of cells. A tumor had formed.

A tumor… in the Drosophila eye. In fact, the researchers carried out their experiments on vinegar flies, which are widely used in oncology. And rightly so: as different from humans as they may seem, they have many key genes in common in the development of cancer. Additionally, they are easy to use and inexpensive to maintain, making them a popular model organism for studying cancers.

You have 43.64% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.

1714627177

#Discovery #cancer #DNA #mutation