In recent years, there has been a growing body of research exploring the development of Parkinson’s disease and its potential triggers. A new study by an international team of researchers sheds light on a compelling model that suggests the neurodegenerative condition might start with the spread of toxic proteins from either the brain or the gut, sparked by damage from environmental factors present in both regions.

The study proposes that substances inhaled through the nose, impacting the brain’s smell center, and ingested through the stomach might both be responsible for Parkinson’s disease. This systemic disease theory challenges the traditional view that the loss of neurons associated with Parkinson’s primarily stems from olfactory nerves in the brain or nerves in the gut. Instead, it suggests that environmental factors play a significant role in triggering the disease.

Neurologist Ray Dorsey from the University of Rochester Medical Center comments on this groundbreaking theory, stating that Parkinson’s disease is likely tied to environmental factors increasingly recognized as major contributors to the disease. He adds that the initial roots of Parkinson’s may begin in the nose and the gut, both structures in the body closely connected to the outside world.

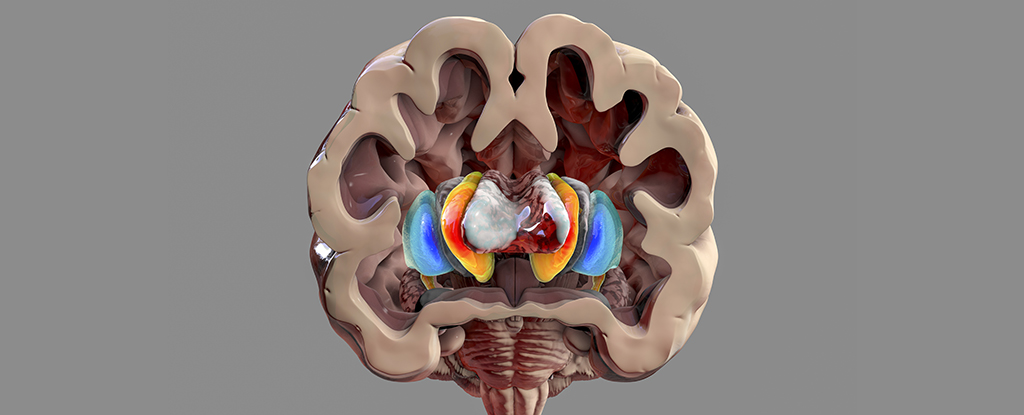

The research team points to various environmental toxicants that potentially trigger breakdowns in brain function, including dry cleaning and degreasing chemicals, air pollution, the use of herbicides and weed killers, and contaminated drinking water. These toxicants are believed to lead to the misfolding of a protein called alpha-synuclein, which then accumulates in clumps known as Lewy bodies. These clumps are responsible for the degeneration of many of the brain’s nerve cells, particularly those involved in motor control.

While this study is purely theoretical, it references previous confirmed links between Parkinson’s disease and environmental hazards. However, understanding these connections more precisely will take time and further research. Factors such as the timing, dose, and duration of exposure, as well as interactions with genetic and other environmental factors, are believed to determine the likelihood of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Although this new theory poses several unanswered questions, such as the role of the skin and microbiome and the impact of prolonged exposures over time, it emphasizes the idea that Parkinson’s disease, as the world’s fastest-growing brain disease, may be fueled by toxicants and is therefore largely preventable.

Moving forward, these findings open up possibilities for future research and potential preventive measures to mitigate the rising prevalence of Parkinson’s disease. Understanding the environmental triggers and the interplay with genetic factors can help identify at-risk individuals and develop targeted preventive strategies.

Furthermore, these findings raise broader implications for public health and environmental policies. The study suggests a need to reevaluate regulations around chemicals used in various industries, such as dry cleaning and degreasing, and to address air pollution and contamination in drinking water. By prioritizing environmental sustainability and reducing exposure to these toxicants, societies can potentially reduce the burden of Parkinson’s disease and other related conditions.

It is important to note that Parkinson’s disease is a complex condition influenced by a multitude of factors. However, this new theory provides valuable insights into the disease’s origins and offers a potential path for interventions and preventive strategies in the future.

As research in this field continues to progress, industry stakeholders, policymakers, and healthcare professionals should collaborate to prioritize funding and support further studies. By gaining a deeper understanding of the environmental triggers and risk factors associated with Parkinson’s disease, we can work towards a future with reduced incidence and improved quality of life for those affected by this debilitating condition.