He shoots himself into the air and is a national hero. Contemporary historians are blowing him off his pedestal; he is a fallen hero. What has happened to the most famous orphan from the Burgerweeshuis in Amsterdam in the meantime? And who is he?

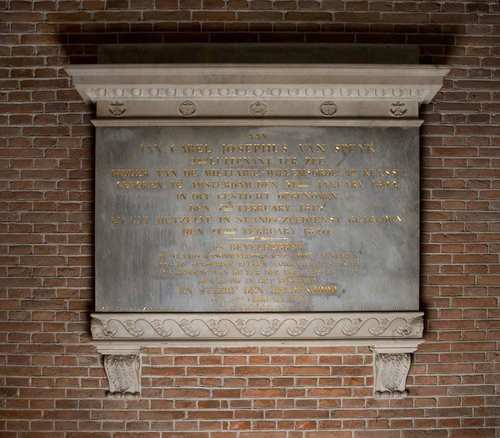

In the corner of the Boys’ Courtyard, once morest the old entrance of the former boys’ house, a plaque has been built in. A history book on the wall. The memorial was erected for one of our great national heroes who, as a sad orphan boy, reluctantly took his first steps over the threshold of the Burgerweeshuis in 1813.

That orphan boy was born on January 31, 1802 as Jan Carel Josephus van Speijk in Amsterdam, the son of a stockfish merchant. Disaster strikes early in his life. When Jan is four his father dies, six years later his mother follows. Our national hero-to-be is now an orphan. He is registered in the orphanage on February 5, 1813. There he turns out to be anything but an exemplary boy. A keg of gunpowder? In 1815 he was apprenticed to a tailor in town. And here too Jantje cannot be kept for long; he wanders from boss to boss. Incited by his older brother Adriaan and other orphan boys, he finally reports to the Navy. He is short in stature and much to his chagrin is rejected. In 1820 he succeeds. He signs up for his sea baptism. After just one expedition, he returns to one of his former teachers. But the sea is now in his legs and a year later he chooses the open water once more. He gets an appointment in the Navy, where he eventually makes it to Lieutenant ter Zee of the second class. Little Jan van Speijk is given command of gunboat no. 2.

Self-Sacrifice of Van Speijk, Barend Wijnveld, ca. 1831

Then rather take to the air just like Van Speijk

In 1830 the southern Netherlands rebel once morest the authority of King Willem I. They want to secede. An independent Belgium emerges. Van Speijk gets caught up in this battle. It is February 5, 1831, a bleak day. There is a gale force wind. Jan lies with his small gunboat in front of the port of Antwerp. He checks shiploads for war equipment, which is followed by seizure. His anchored ship is knocked loose by the wind. It floats to shore and is thrown once morest the quay wall. A furious crowd of Antwerp residents and soldiers awaits him there. The insurgents try to get on board and lower the Dutch flag. That action goes down the wrong way with the patriotic Jan. He disappears into the cabin and puts a burning fuse, possibly a cigar, in an open powder keg. While pronouncing his famous last words ‘then rather into the air’, he blows himself up. He thus prevents his ship from falling into the hands of the Belgians. He takes almost the entire crew with him to death; the number of Antwerp citizens killed is and remains unknown. A few days later, on February 9, he is fished out of the Scheldt. At least what’s left of Jan. His head and limbs are missing. His body is identified by the knight’s cross of the 4th class of the Order of Willems, with which he was decorated following a heroic performance in an earlier battle. It sits proudly on his chest. His remains are sent to Amsterdam in formaldehyde. Jan now not only wears a ribbon, but also the status of national hero. A year later, on May 4, 1832, he was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk. Prior to this, a long funeral procession passes through the city. The regents of the Burgerweeshuis lead the way.

Portrait of Jan van Speijk, Carel Frederik Curtenius Bentinck, 1831

Hero worship

As soon as the smoke clears, another explosion follows. This time of fervent patriotism. Jan is revered as a national hero and now fits in the ranks of Hein, Tromp and De Ruyter, his illustrious predecessors. His worship spreads like an oil slick over the land. Numerous artists and musicians honor Van Speijk in their work, praise poems are written and commemorative medals are minted. A national lottery is also being held to raise money for a monument. If what can still be snatched from our hero’s torso and everything that has come into contact with him will be sold as true relics.

Memorial stone for Jan van Speijk, Amsterdam Museum

Memorial stone

From splinters of wood from the gunboat to tufts of hair and a rib; the Amsterdam Museum alone has one hundred and fifty Van Speijk-related objects in its collection. Most striking is the memorial stone that is bricked into the wall of the boys’ orphanage, the current entrance to the museum. City architect J. de Greef is responsible for the design, stonemason Chr. Sigault elaborates the design. When placing the memorial, it is not enough to simply brick in the stone; the colonnade is extended in front of it. Two new columns will be placed and the space thus created will be tiled and fitted with new fencing to give the monument the necessary cachet.

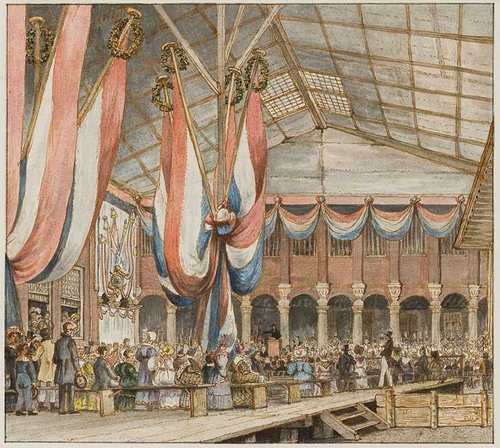

Unveiling of the monument to JCJ van Speijk, Gerrit Lamberts, 1831

On October 20, 1831, the plaque is unveiled by the regents in front of a large audience. The boys’ place is largely covered with a cloth and festively decorated. For 25 cents you can view two paintings in the orphanage. Van Speijk putting the burning fuse in the powder keg’ by J. Schoenmaker Doyer and ‘the explosion of the gunboat no. 2’ by Willem Pieneman. It was there early on, that museum destination.

Criticism

From the second half of the nineteenth century this revelry is tempered. Criticism rears its head. Van Speijk’s hero status is wavering. Marine historian Ronald Prud’homme van Reine wins in his 2016 Preferably not in the air no wipes. Jan acts during a truce. The role of the military in storming his gunboat is negligible. There is therefore no question of a life-threatening situation and there is no reason to intervene. He acts impulsively. His act is of no significance to the course of the uprising. For the sake of convenience, it is ignored that 27 crew members and an unknown number of Belgians were killed. According to Prud’homme, our national hero is anything but a hero: ‘Van Speijk was a tragic figure who slowly drifted towards suicide, partly due to his lonely existence as an orphan. His act brought great embarrassment to the army and navy leadership. There were many deaths and a precious ship was lost and all that for nothing. That is why the disaster has been made into a heroic act in propaganda.’ The Royal Dutch Navy distances itself from the qualification suicide attack. ‘Jan acted defensively and not offensively’. According to Prud’homme, it was indeed Jan’s intention to drag as many Belgians as possible into death. (Brabants Dagblad, 1 October 2016)

‘Good example’ makes good follow?

Impulsive or not, Jan’s rash act of heroism does not come completely out of the blue. Rather, he utters his ‘last words’ in a letter to his niece. On December 19, 1830, he writes to her: ‘that sooner will the boat and gunpowder and me go into the air than ever become an infamous Brabander or surrender the vessel’. He mirrors Reinier Claeszen, commander of a fleet of the Dutch navy, who blows up his ship near Portugal in October 1606 to prevent it from falling into Spanish hands. On New Year’s Eve in 1830, he tells his own sailors that he will light the gunpowder if his ship runs aground and is threatened by Belgian insurgents. Previously, gunboat commanders had already told each other that they preferred certain death to ill-treatment. They will not tolerate any encroachment on Dutch fame and honour. And Jan, did he want to keep to that appointment or is he perhaps the dreamy orphan boy, a romantic who wants to be mentioned in the same breath as his great heroes, or is he still the tormented man, a suicide? Who knows may say!