What determines what we believe regarding the world, ourselves, our past, and our future? Cognitive neuroscience suggests that our beliefs depend on the activity of our brain, specifically how it processes sensory information to make sense of our environment.

These beliefs (defined as probability estimates) are at the core of predictive brain processes that allow our brains to predict the probabilistic structure of the world around us. These predictions may even be the building blocks from which our mental states, such as perceptions and emotions, are built.

Thus, many psychiatric disorders, such as depression or schizophrenia, are characterized by unusual beliefs whose origin is difficult to understand. However, if the brain systems that underlie them are well identified, they might constitute an important target of therapeutic action to alleviate the suffering associated with these disorders.

How does ketamine work?

This is suggested by the study that we recently published in the journal JAMA psychiatry. We have explored the effect of the dissociative psychotropic drug ketamine on belief updating mechanisms (how we change our beliefs in response to information) in patients with treatment-resistant depression.

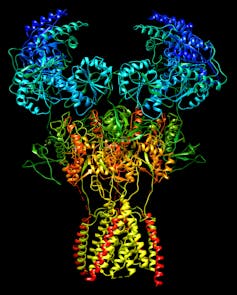

While conventional antidepressants take several weeks to become effective, ketamine, which is an NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor antagonist on neurons, produces initial antidepressant effects within hours. During its administration, it also causes a dissociative experience of depersonalization with the sensation of leaving one’s own body or autoscopy.

This rapid onset of action and unexpected dissociative effects raise questions regarding the processes involved in its therapeutic efficacy, and constitute a mystery on the border of pharmacology and neuroscience.

Cognitive-affective biases in depression

According to the World Health Organization, depression affects regarding 280 million people worldwide and causes 700,000 to commit suicide each year. Depressive beliefs (pessimism, devaluation, rejection, experience of failure) are one of the most characteristic symptoms. It is said that these negative themes are congruent with the mood, since their content is homogeneous with the affective tone of the subject.

These beliefs are crucial because they influence perception and actions, causing a phenomenon of negative self-reinforcement. The belief of being rejected by the environment progressively promotes withdrawal, in turn reinforcing the belief of being “useless”. Once the loop has closed on itself, it is difficult to get out of this vicious circle.

fran_kie / Shutterstock

Since the investigations carried out by the psychiatrist Aaron Beck, a large number of works have suggested that the way in which information is encoded in belief networks according to its valence (its positive or negative character) may be involved in the generation of these beliefs. depressive.

In fact, it has been shown that we tend to encode preferentially positive information. This phenomenon, called affective bias, is responsible for generating slightly more positive beliefs than reality: we tend to believe that we are smarter, more attractive, better drivers, or better lovers than statistical reality.

In depression, this bias disappears or is reversed: patients integrate more negatively valenced information, generating darker beliefs regarding the world, themselves, or the future over time. This affective bias reversal phenomenon may be one of the keys to understanding the origin of depressive beliefs.

How Ketamine Affects Beliefs

We started our study as a result of a surprising clinical finding in our unit at the Hospital Pitié-Salpêtrière (Paris). Patients with resistant depression who received ketamine for antidepressant purposes reported to us a strange feeling: following treatment, their view of the world seemed to have changed, as if their perspective were different.

The negative beliefs that had accompanied them for several months seemed to vanish. Some patients even expressed a sense of strangeness at these thoughts, as if they had belonged to someone else. Most intriguingly, these changes appeared to be directly associated with the antidepressant efficacy of treatment, although the causality of this link was not understood.

In view of the reports of our patients, we suspect an effect of ketamine on the mechanisms for updating beliefs. In an attempt to understand this phenomenon, we conducted an experiment to test the effect of ketamine on the way we generate beliefs, in this case a pre- and post-treatment task.

In this experimental task, we asked subjects to estimate their probability of experiencing 40 future negative events (for example, being bitten by a dog or having a car accident), as well as other estimates that might influence the processes studied. Next, we look at how their estimates of these 40 negative events were affected, depending on the valence of this information.

Only four hours following ketamine administration, we found a significant decrease in the integration of negative information into belief generation: the affective bias towards positive information was restored in patients with resistant depression. Most surprisingly, this effect was directly associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms at one week, suggesting that these cognitive changes may precede clinical improvement.

future prospects

C22H31NO2CC BY-SA

More research is still needed to understand the brain processes associated with these changes, but there is considerable evidence that NMDA receptor-mediated signaling is involved. These neural receptors intervene precisely in the excitation-inhibition balance of the brain, and seem to be crucial for the prediction processes and brain plasticity.

The direct action of ketamine on the activity of these receptors would therefore constitute a direct pharmacological pathway for modulating the predictive mechanisms, which would explain both its fast-acting antidepressant effect and its dissociative effect. By modulating the way the brain uses sensory blocks to build beliefs, ketamine may be able to modify the mechanisms underlying depressive beliefs.

These hypotheses open many perspectives for the development of treatments directed at these brain processes, or the combination of these molecules with augmentative psychotherapies that operate specifically on belief systems. This goal is currently at the center of the so-called psychedelic medicine debate, in particular for psilocybin, a hallucinogenic molecule with rapid antidepressant effects like ketamine. Perhaps this is the path to follow for the reconciliation of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches in psychiatry?