By Alica Ouschan

Toiling hard, rubbing oneself sore, barely making ends meet – that’s roughly how the dialect word “fretten” can be translated. And that’s what happens to the protagonist of the novel “Fretten” and the characters who surround her: they struggle through life.

In 2020, Helena Adler, author and artist from Salzburg, published her first anti-Heimatroman with “The Infanta wears the crown on the left”. Now there’s a sequel that makes at least as much impact as its predecessor.

From the infanta to the mother animal

With a sharp-edged tongue, Helena Adler tells of the illusion and idyll of country life. Her language is characterized by a wise and analytical sharpness, which feels unusual for a character with an uneducated and socially weak reality of life. Even in her first book, the stories sounded like observations through children’s eyes in the words of an adult linguist.

The fresh blood in my veins is the red thread in my stories and the blush on your face.

Eva meets photography

Helena Adler is on the long list with “Fretten”. Austrian Book Prize 2022.

In contrast to part one of the stories from the life of the youngest daughter of a bankrupt farmer, the protagonist in “Fretten” is no longer a child, but a young woman who joins criminal gangs who plunder villages and smuggle drugs. The image of the reality of a young woman in the countryside with no destination or perspective, in all its horror, takes on a new hue the moment the former Infanta becomes a mother.

Home looms over everything like a shadow. With the horrors of the past on her back, the protagonist tries to cope with her new role, while family traumas creep in between the acrobatic sequence of visually stunning sentences.

Young and young demand

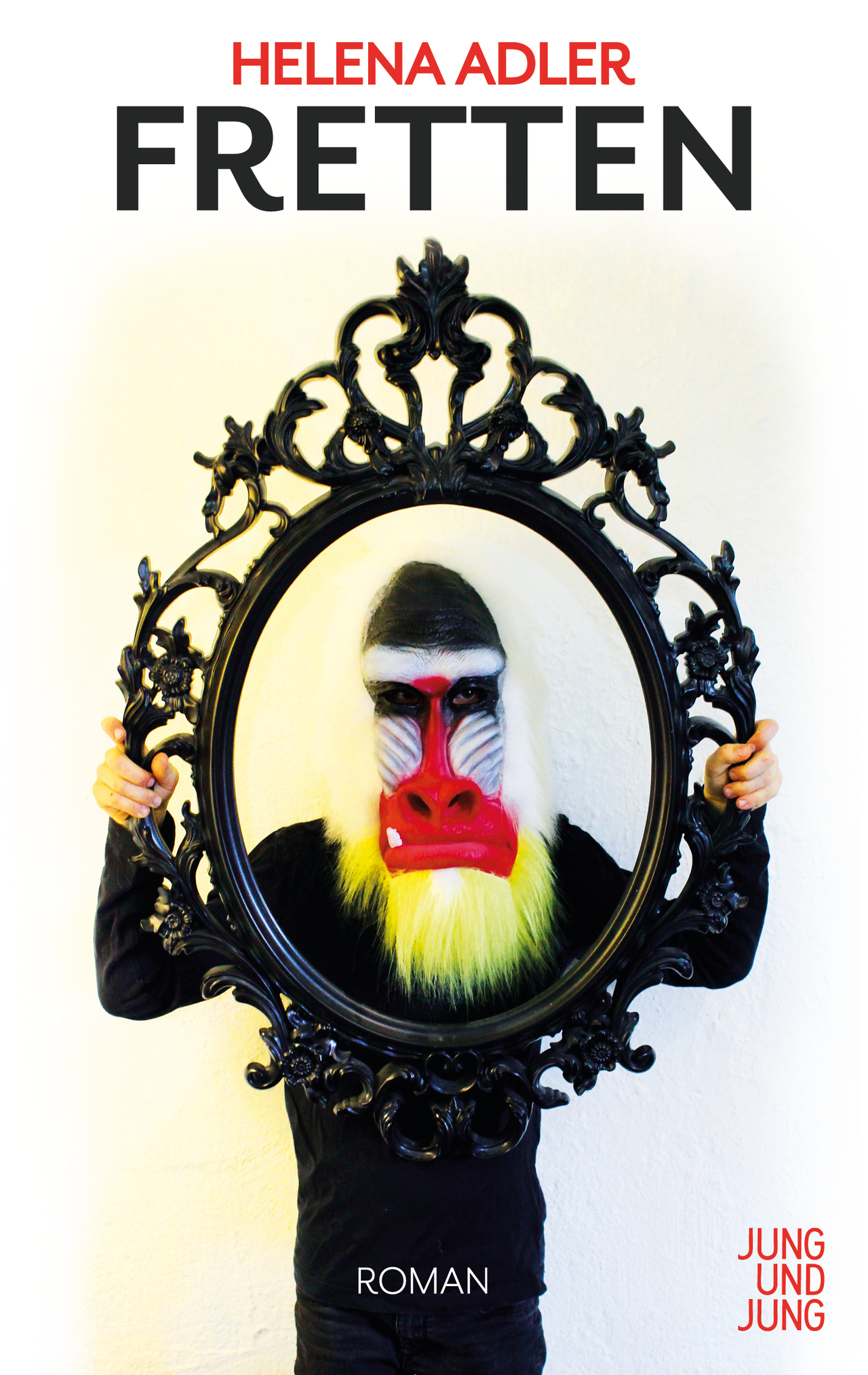

“Fretten” by Helena Adler was published by Jung and Jung Salzburg.

“I built, sewed and made a mother’s costume, it never sleeps. It’s a mommy costume, a universal maternity dress with tons of space pockets underneath that has space for planets and cookies.”

The new mother projects repressed war memories of the tormented grandfathers and great-grandfathers, which convey a distorted image of masculinity, onto her son. She realizes that no matter how many times she cuts off, rips out and replants her roots, weeds just don’t die.

Helena Adler does not work on this between the lines, but with the ugliest clarity. Helena Adler is celebrated for her novels, compared to Thomas Bernhard and Elfriede Jelinek. In contrast to these two Austrian literary greats, Helena Adler writes less grumpily or cryptically, but with a clear, purposeful anger and a gallows humor that hops along on one leg at the pain threshold.